Despite verbal support for an independent Chechnya, Ukraine has abandoned Chechen fighters who have been fighting on their side against Russia for a decade. Is Russian cultural influence and propaganda the main reason behind this, and if so, what does it mean for Ukraine’s ability to stand against Russian aggression in general?

In October 2022, Ukraine’s parliament recognised the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria as an independent state that is ‘temporarily’ occupied by Russia, and condemned ‘the commission of genocide against the Chechen people’.

While this might seem a significant act of solidarity, to Chechens who had long been fighting to defend Ukraine from Russian incursion, the gesture was welcome but insufficient.

Despite the fact that Chechens were one of the first nations to support Ukrainians in their struggle against Russia, a combination of deep-rooted Russian ideology and a lack of political will have meant that Ukraine’s government has failed to offer Chechen fighters any real protection, while the Ukrainian media and influencers continued to spread anti-Chechen stereotypes.

A constant risk of deportation

Chechen volunteer battalions have been fighting in Ukraine since 2014, after Russia occupied Crimea and backed separatist movements in Donbas. But to this day, the vast majority of pro-Ukrainian Chechen fighters do not have Ukrainian citizenship.

Moreover, despite the Ukrainian Parliament recognising the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria as ‘temporarily occupied’, and the Parliament also recognising the rights of the neighbouring ‘brotherly’ Ingush nation to independence, Ukrainian authorities continue to legitimise the Russian authorities’ right to decide the fate of pro-Ukrainian Chechen and Ingush activists.

For example, blogger and former spokesperson of the pro-Ukrainian Sheikh Mansur Battalion Islam Belokiev is currently at risk of being deported from Poland to Russia after he left Poland using a Russian passport, the only travel document he had. As a ‘minor crime’, such an action does not warrant the death penalty — yet in Russia, Belokiev would undoubtedly be tortured or killed.

The occupying Russian government is reliably brutal towards any Kremlin critics in the North Caucasus republics, kidnapping and torturing not just dissidents, but also their families.

There is clear evidence that Ukraine could help Chechen refugees or condemn them: in 2019, the Ukrainian government handed over Timur Tumgoev, a pro-Ukrainian volunteer fighter of Ingush origin, to Russia. Tumgoev was brutally tortured and then sentenced to 18 years in a maximum security prison on false charges of terrorism.

It is important to highlight that Russian authorities have long had a flexible attitude towards the truth: Tumgoev was accused of fighting for Islamic State in Syria, despite a lack of supporting evidence, while the invasion of Ukraine was justified by claiming that Ukraine was harbouring Nazis. Russia’s accusations and demands towards those that oppose it cannot be taken as bearing any relationship to the truth.

The Sheikh Mansur battalion has fought in Ukraine since 2014, and a Ukrainian passport, or even support for Belokiev’s case from Ukraine, could quite literally save his life.

Nonetheless, Kyiv still refuses to provide any guarantees to Chechen and Ingush fighters risking their lives to defend Ukraine. Ukrainian authorities have even requested clear criminal record certificates from the Russian authorities before considering allowing Chechens to apply for Ukrainian citizenship, despite knowing that many Chechen and Ingush activists have been targeted with fake terrorism claims in Russia. In doing so, Ukrainian authorities not only ignore the fact that Russia fabricates accusations against dissidents, but de-facto recognise the legitimacy of the political system that is occupying Ukrainian land right now.

Such a dystopian state of affairs does not exist in isolation. The discrimination against Chechen fighters goes hand in hand with verbal discrimination by Ukrainian influencers, and even the Ukrainian president himself, an attitude ironically rooted in Russian ideology.

A short history of Chechen-Ukrainian relations

On the afternoon of 12 October, an explosion destroyed a petrol station in Chechnya’s capital, Grozny. The tragedy took the lives of four civilians, including a woman and two small children.

But Ukrainian blogger and social media influencer Dmitro ‘Apostol’ Karpenko commented on the situation with a weird sense of satisfaction, calling the victims ‘bearded people’ who had become ‘cargo 200’ — the Russian code for military casualties. The reference to bearded people was more a lazy use of an Islamophobic cliche than an attempt to spread disinformation, as the victims’ identities were widely known.

So why did a Ukrainian blogger consider Chechen civilians legitimate military casualties?

This blogger in particular was known to have asked xenophobic questions to Russian prisoners of war of Chechen origin, accusing them of ‘not allowing their women’ to marry Christian Orthodox men and peddling worn-out stereotypes.

While this could be interpreted, perhaps overly charitably, as a manifestation of a broader hate towards Ukraine’s enemy, it is important to understand that Chechens are not enemies of Ukraine.

Chechens fighting for Russia were mostly forced into the war through torture, blackmail, or kidnapping, sometimes even as retaliation against relatives in Europe who demonstrated a pro-Ukrainian position. In contrast, ethnic Russians were mostly registered above board, after receiving conscription papers.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given such pressure, opinion polls have consistently found Chechnya to be the most anti-war of the ‘Russian regions’, and much more opposed to war than residents of the Russian capital.

Chechens living in Europe have also since the start of the war shown support for Ukraine and Ukrainians: organising protests, sending humanitarian aid, and going to fight on the frontline. And such solidarity is widespread, with all major Chechen independence movements unanimous in their pro-Ukrainian positions, despite significant differences of opinion on other matters.

Having been through two brutal Russian-Chechen wars, the Chechen people cannot forget the suffering they have experienced at the hands of the Russian military, prompting an understandable empathy towards Ukrainians. Most Chechens also have a deep understanding of how Russia operates and oppresses, in contrast to many Western observers.

Chechens and Ukrainians also have a long history of collaborating on the anti-imperial struggle. In 1932–1933, some victims of the man-made Holodomor famine found refuge and food in Chechen houses after fleeing Ukraine, before Chechens also became victims of Joseph Stalin’s genocide in 1944.

In 1994, during the first Russian-Chechen war, a group of Ukrainian volunteers under the command of Ukrainian activist Oleksandr Muzychko came to Chechnya to fight on the Chechen side. Later, Muzychko became one of the most prominent figures in Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity in 2014, when Ukraine’s fourth president and pro-Russian proxy Victor Yanukovych was ousted. Muzychko was also a key figure in establishing the Ukrainian volunteer battalions in 2014.

But despite such longstanding ties and similarities, most modern Ukrainian media and politicians do not display any understanding towards Chechens.

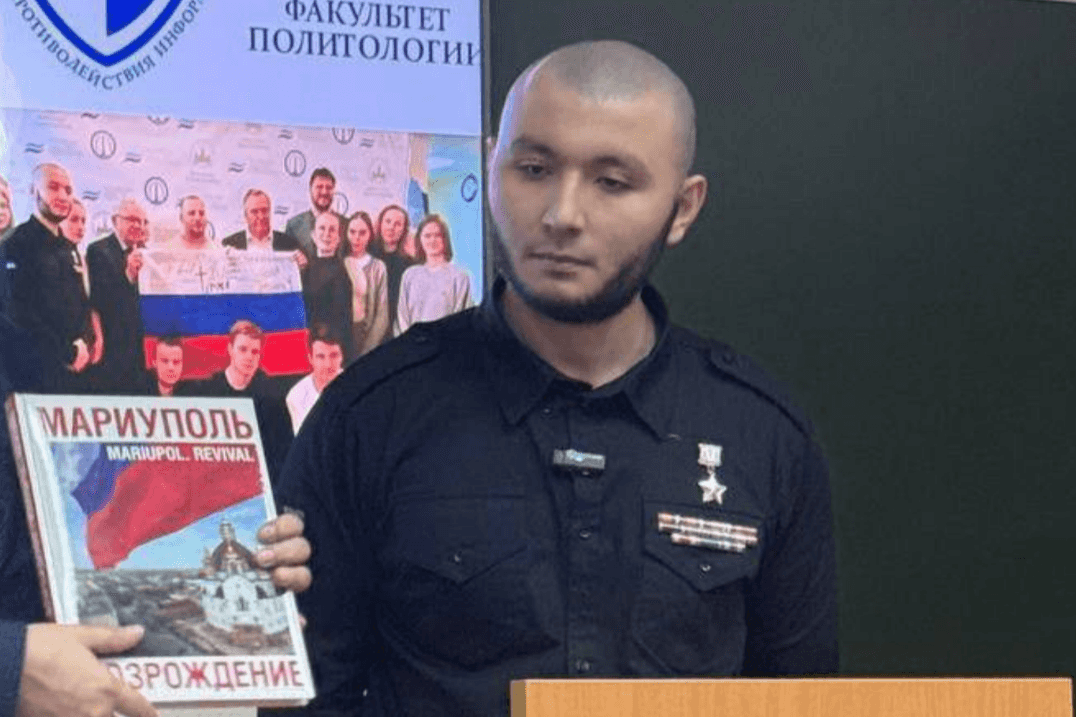

Ukrainian media frequently do not distinguish between ‘Kadyrov’s people’ fighting for Russia and ordinary Chechen people, blaming Chechens as a whole for Russian war crimes in Ukraine. Media also does not note that ‘Kadyrov’s’ brigades are made up of people of a number of ethnicities, and not only Chechens. Ali Bakaev, a representative of the Sheikh Mansur battalion, told me that nearly 70% of fighters in Kadyrov’s Ahmad battalion are not ethnically Chechen.

On top of this, even to buy into the notion of Kadyrov having his own troops is contentious: can ‘Putin’s foot soldier’, in Kadyrov’s words, really have his own people, or are his forces just a part of the Russian army? In my opinion, Ukrainian and Western media believe that Kadyrov has more independence than he actually does.

Even Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyi has expressed anti-Chechen sentiments, saying in August that the Deputy Head of the President’s Office, Oleg Tatarov, and the leader of the Ukrainian secret service, Vasilyi Malyuk, had killed ‘Chechens in Kyiv’ to justify their need for protection. Ukrainian media later clarified that the Ukrainian president was clumsily trying to say that the Ukrainian officials were hunting Russian killers of Chechen origin, but the xenophobic sentiments in his statement are obvious.

When such notions are put forward by the country’s highest authority, it is perhaps unsurprising that pro-Ukrainian Chechen fighters remain unprotected.

‘Only the highest authority of Ukraine, I mean, the Ukrainian president, can improve the situation of the battalions,’ Bakaev explains.

He says that he felt betrayed by the West and the Islamic world that abandoned Chechnya in its struggle against Russia, and hoped that at least Ukrainians would understand his nation’s four hundred years of anti-colonial struggle.

But it is not just about Chechnya. As a Ukrainian citizen and political analyst, I see that the situation is much more critical. To win the war with the Russian Federation, Ukrainian politicians first and foremost need to win the fight against Russian propaganda in their own minds.

Getting rid of the ‘master’s tools’

American civil rights activist Audre Lorde famously wrote that the ‘master’s tools will never dismantle the masters’ house’, but this is essentially what the Ukrainian government is trying to do with Russian domination in Eastern Europe. To free the country from both its Soviet legacy and Russian political influence, they need to first and foremost get rid of the ideas that the Kremlin has put in their minds.

At my school in Donetsk, ‘anti-terrorism’ was a special topic which was raised during our history lessons. At those times, the teacher, who was also our school head, told us about ‘horrendous terrorist acts committed by Chechen terrorists on Russian territories’. We didn’t learn that the first Russian-Chechen war was a purely national-liberation struggle, or that Chechens had never chosen to be a part of Russia. We didn’t learn about Chechen schools and hospitals that were bombed by Russian missiles. In those lessons we had, Chechens were to blame for everything, and the story of the Russian-Chechen war was told from a Russian imperialist perspective.

No wonder that later it was the Donetsk region that showed extremely pro-Russian sentiments: the older generation was brainwashed by the Soviet propaganda, and even the millennial and zoomer generations of Donetsk were taught to see the world from a Russian point of view.

Anti-Chechen propaganda during both Russian-Chechen wars on Ukrainian TV made the nations’ minds blurry toward any potential threats from Russia. Before the full-scale invasion in February 2022, my Ukrainian friends in the Donbas region were extremely optimistic, refusing to leave Mariupol with their families before the bombing started. They couldn’t believe that the Russians could be so brutal.

But if my Ukrainian friends knew more about the annihilating Russian bombings of Grozny or the massacres in Samashki village, they may have had more chances to save their own families.

The fact that Ukraine is not showing their Chechen soldiers appropriate support is a symptom of a bigger problem — a Russian domination over political thinking in Ukraine.

For years, the Kremlin has set their potential victims against each other, acting on the principle of divide and rule. Therefore, now more than ever, it is vitally important for Ukraine’s leaders to get rid of Russia’s imperial stereotypes, and finally realise who their real allies are.