Review | Shared Document — an exhibition by emerging Georgian artists

This group show by four young professionals introduces their practice and a glimpse into the kind of environment Georgian artists are facing.

With the adoption of numerous repressive laws — from the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) to the anti-LGBT propaganda law — Georgian artists must currently navigate a complex socioeconomic and political landscape.

Acquiring funding for projects has become more difficult, sometimes even potentially dangerous. Where to exhibit, which platforms and organisations one should align with, and where to obtain funds are decisions that come with certain consequences. Each step has an impact not just on the lives of the artists themselves, but also on the environment they are working in.

The Shared Document exhibition comes just at this time, when the heartbeat of young Georgian art seems to be shifting more towards independent, artist-run spaces, and the underground.

The show brings together works by four 2025 graduates of the Free University of Tbilisi’s Visual Arts and Design programme — Mari Babaevi, Tinatin Goglidze, Mari (Makhi) Makharoblishvili, and Saba Khechosvili — who have been sharing a studio since 2022. After finishing their studies, they decided to come together one more time to make a self-curated group show at Chaos Concept, a concept store and small exhibition space that hosts shows by young Georgian artists. The artworks in this show are a continuation of each artist’s diploma projects.

Mari Babaevi — where the home is

Born and raised in Georgia, Babaevi draws inspiration from her Azerbaijani heritage. Her art is a glimpse into a world within a world, focusing on themes of memory, family history, and heritage. Gender roles and the female experience of certain cultural customs are concepts that often surface in Babaevi’s work.

A storyteller at heart, she works in different mediums — illustration, textile, sculpture, and text. Babaevi frequently uses different languages and scripts in her art, further accentuating her roots and rich cultural background.

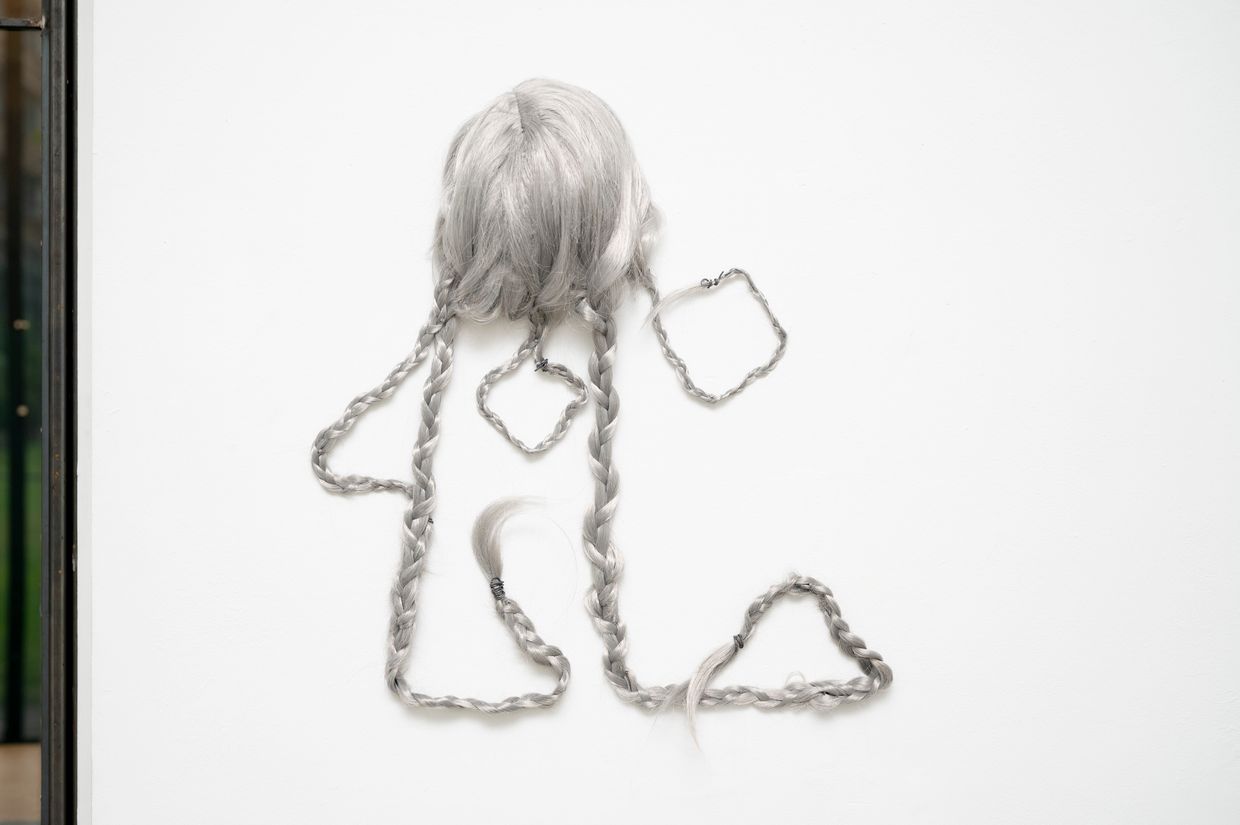

Two of her works are featured in the installation, one of which is a braided silver wig hung on the wall. The almost distractingly shiny, synthetic braids are contorted into shapes vaguely reminiscent of the Persian script.

The braid motif often appears in Babaevi’s work — it is a versatile image that has many interpretations, symbolising unity and strength, as well as intimate rituals of care between people. The name of the artwork — ‘Khāneh’ — means home in Persian, a reference to the author’s lost Iranian roots. As a fifth-generation Azerbaijani living in Georgia, the origin of the Babaevi family name is not entirely clear, tracing back both to Turkic and and Persian cultures.

Separately, on the floor, there is a piece of fabric with the shape of someone’s feet on it. The use of contrasting shapes and cut-out layers of fabric that interact with each other is a technique Babaevi often uses in her work, giving it an intimate feel. Together, the two pieces invite the viewer to step into an exploration of the physical and emotional boundaries of a home and all that it can encompass. The work is imbued with a sense of longing and melancholy.

Saba Khechoshvili — tracing the space around us

Khechoshvili’s work is deeply inspired by the spaces we inhabit. He is interested in architecture and the daily dynamics of a home and the objects inside it, often exploring what happens when things are taken out of their original context. He uses a wide range of mediums in his art, including drawings and sculpture, as well as audio and video installations.

Perhaps as one might expect, his art often features elements from his own home, his personal space. These elements are usually juxtaposed with materials found in another space that has had a significant influence over Khechoshvili’s practice — for example, his father’s industrial studio that produces plastic and various other materials. Khechoshvili often uses the leftovers that accumulate in the studio, sometimes displaying them as they are without much intervention and other times carefully incorporating them into entirely new contexts.

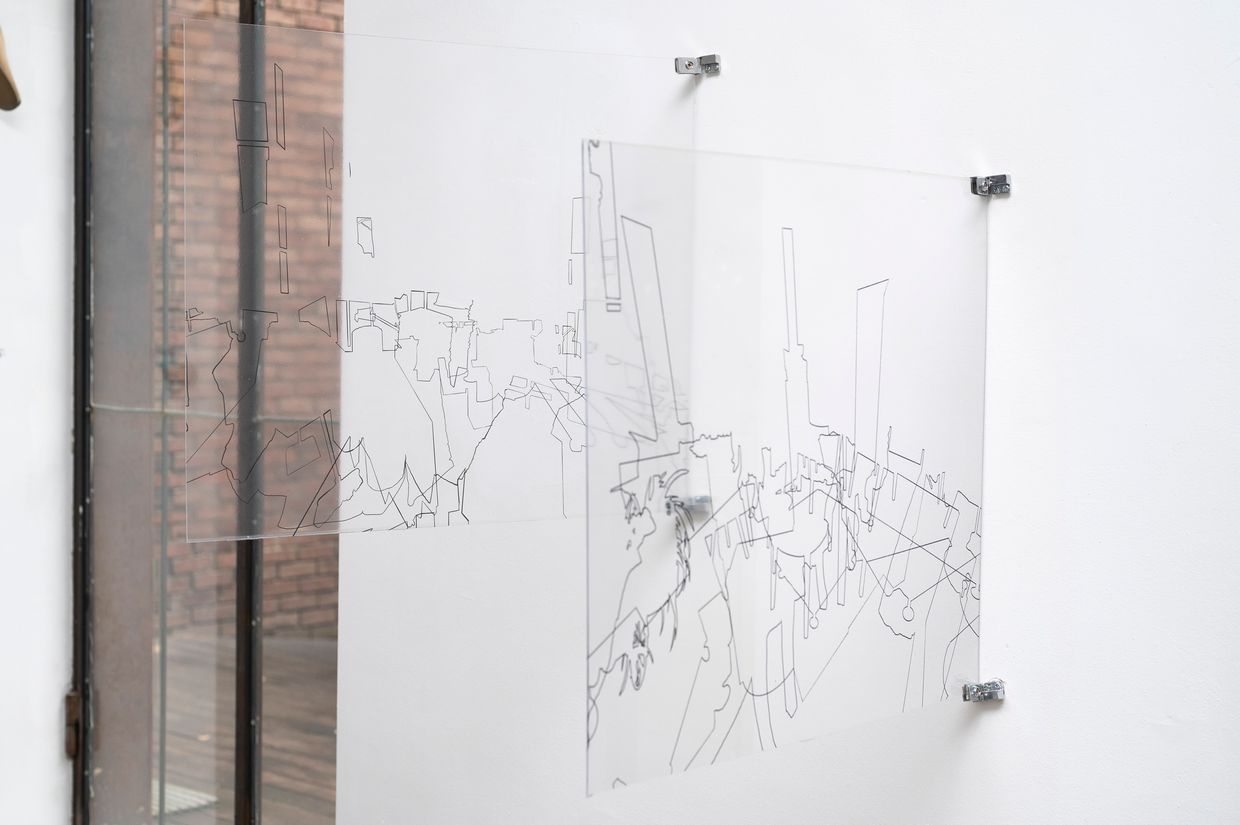

The Shared Document exhibition features two of Khechoshvili’s works from his ‘Deconstruction’ series. Two acrylic glass plates with abstract outlines on them are mounted on the wall. On the floor, there is a piece made of found objects, a reference to materials from Khechoshvili’s father’s studio.

The jagged outlines of the sculpture on the floor and the patterns on the glass are both created using a method that appears in many of Khechoshvili’s works. After taking pictures of spaces that interest him, Khechoshvili focuses on unexpected details by tracing the outlines of negative spaces in these images. His work is mostly site-specific, meticulously placed in a way that affects how viewers move around in space.

Although the artworks in this show are smaller in scale than other monumental installations Khechoshvili has done, they still have the same compelling presence and interact with their environment in unexpected ways.

Mari (Makhi) Makharoblishvili — the language of symbols

Makharoblishvili is interested in post-internet culture. Themes of nostalgia, social narratives, and the public unconscious often surface in her art. In her works, Makharoblishvili playfully examines the constant onslaught of visual information and the flow of images on the internet. She likes to explore iconic pop-culture images and web emoticons as tools that can be used to create new language systems online. Testing the boundaries between virtual and physical reality, Makharoblishvili mixes elements from both of these worlds in her art, working with manipulated images, illustration, prints, text, and sculpture.

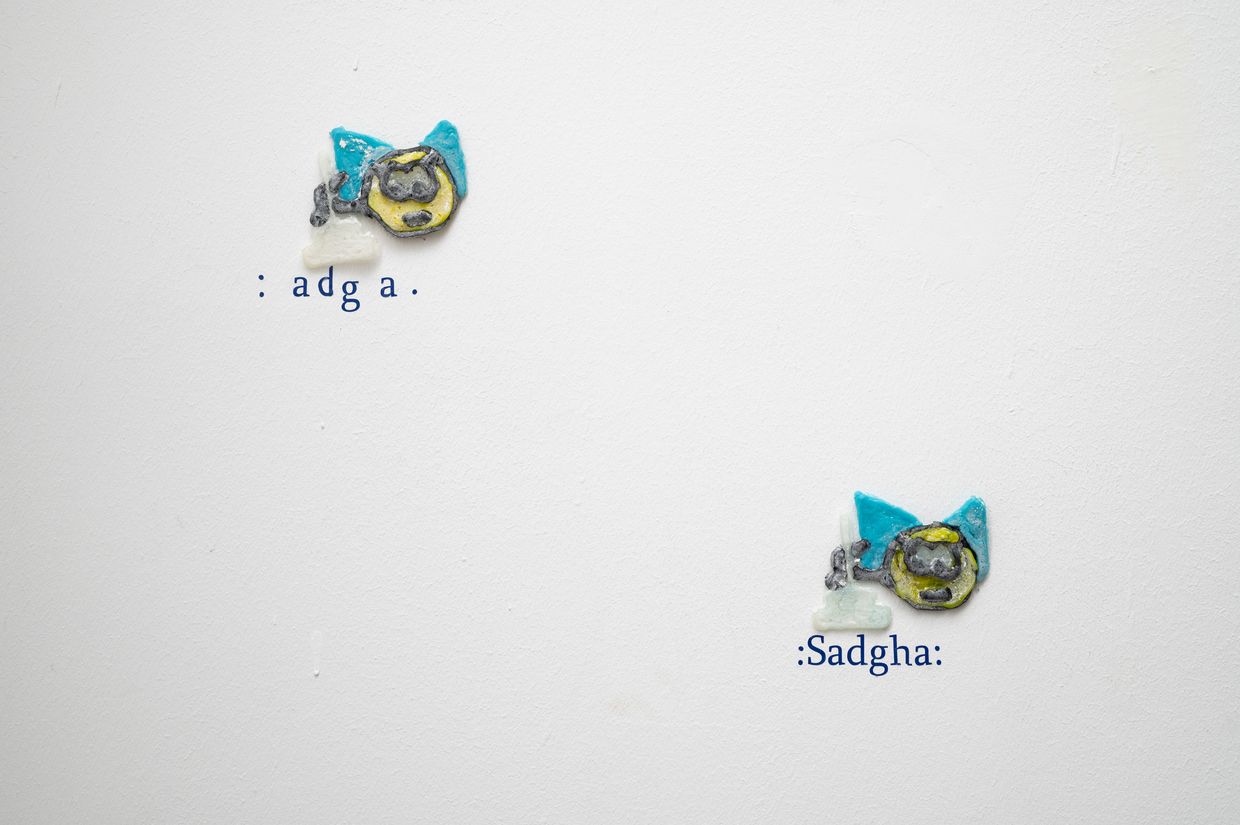

As such, her work, appearing at first as tiny bug-like dots, is scattered around the entire exhibition space. Upon closer inspection, these dots turn out to be little silicone sculptures in the shape of old-school forum emoticons, a little bit warped, but still cheerfully coloured. They are accompanied by text in a blue script, reminiscent of forum codes for emoticons from Tbilisi Forum’s website.

Underneath each sculpture is the word ‘Sadgha’, a Georgian word with a layered meaning that alludes to something that no longer exists, the elusive good old days. This kind of vague longing afflicts many in Georgian society, and the word slips into conversation quite often.

Humour as a tool of expression and interpretation can be felt in many of Makharoblishvili’s works, including this one. The dispersed installation invites viewers to play along and search for the tiny sculptures hidden away in unexpected corners or even the ceiling of the room. ‘Plumber with baseless hope for the bright future’ is a fitting title for this playful artwork full of sarcasm and wit.

Tinatin Goglidze — deconstructing football one piece at a time

Goglidze’s art is all about football. Not a player herself, she focuses on the sport through the lens of an outsider. Fascinated by deconstructing the imagery and themes of football, she delves into the very primal form of iconic football elements. Individual parts like the stadium, which can be traced all the way back to the iconic Roman amphitheaters, shin guards referencing armour, or the ball itself, all appear across Goglidze’s art.

Interpreting the symbolic language of football, Goglidze uses it as a powerful tool to address current social issues. She often focuses on themes attached to a person’s gender experience and expression. Goglidze’s art includes illustration, drawing, and installations made with football paraphernalia, textile, and various other mediums.

Goglidze’s site-specific sculptural installations take over the exhibition space. Nude tights are stretched to their very limits across the room, with shoe molds for feet and a football stuck in the groin area. Some parts of the figure are decorated with glitter and nail polish, accentuating common trauma points and intimate areas. This detail further blurs the lines between genders, asking questions about expectations placed both on masculine and feminine gender roles. The sculptural forms in Goglidze’s installation are bold even in the way they are presented in space, not shying away from sensitive subject matter.

The exhibition Shared Document is an important example of a successful collaboration between independent artists. Curating the show together, each person has managed to tell their own personal story, while also taking care of their colleagues’ practice. In the context of the exhibition, unexpected parallels and connections have surfaced between the different artists and their works. With a long road ahead of them, it will be interesting to observe where their artistic endeavours take each of them.

This small exhibition, which only lasted a little over a week, may not have been one of the loudest, most impactful events on this year’s art scene, but it has still managed to capture the zeitgeist. In an environment where opportunities, funds, and platforms are hard to come by, one of the biggest propellers of an artist’s career is the support of other artists, which is what makes independent initiatives like Shared Document especially important to pay attention to. Since the exhibition, some of the artists from Shared Document have announced the creation of a new initiative and artist-run space in Tbilisi called Nakadi, one worth keeping an eye out for in future.