The orphan who found a mother from behind bars in Georgia’s struggle for democracy

When 30-year-old Archil Museliantsi was jailed, a stranger who met him on the streets took it upon herself to become the mother he never had.

The day 30-year-old orphan Archil Museliantsi received his verdict was not an easy one — especially for 62-year-old Tsaro Oshakmashvili. After meeting during the ongoing anti-government protests in Tbilisi, Tsaro has taken on the role of his surrogate mother.

Archil was arrested at a protest on 30 November 2024. On 22 August 2025, he was sentenced to four years in jail on charges of deliberately damaging the wires for cameras installed on the parliament building. The damage was assessed to be around ₾530 ($200).

That day, Tsaro says she had to be strong and hold back her tears, because she knew Archil would be worried about her. He didn’t look at her when the verdict was read out — he later wrote it was because he couldn’t bear to see her cry.

‘It was tough, but also, his humour helped’, says Tsaro, when we caught up with her on the road to Archil’s hometown of Kazreti on 30 August. ‘When the judge announced the verdict, he told Archil he had an option to apply to the president for a pardon, to which Archil cheekily replied: “What president, do we have one?” ’.

Even though she was pessimistic about the trial and didn’t expect him to be acquitted, Tsaro says she had still clinged to a slither of hope that things could play out differently. She remembers cooking a big dinner for her family and saving some of it for Archil. There was also a white shirt, which she bought for him, though she wasn’t allowed to send it in the end.

‘I ironed that shirt and had the dinner ready for him, you know, just in case’.

‘She told me to be proud, to support Archil’

Tsaro, an accountant by trade, first met Archil during the protests that began following the controversial October 2024 parliamentary elections, which saw the ruling Georgian Dream party win amidst widespread reports of fraud.

‘We were all so disappointed’, she recalls. ‘I saw disappointment in the eyes of my children and the youth in the streets. I was so convinced before that we would win the election.’

It was during one of these protests on the city’s Melikishvili Avenue that Tsaro first spoke with Archil.

‘He told me then that he didn’t have parents and that he was ready to die for his country. Our friendship started then’, Tsaro says.

‘It hit me hard when he told me he was an orphan; he was so committed and brave. He told me if something were to happen to him, there would be no one to ask after his well being’.

While these protests continued intermittently, it wasn’t until 28 November, when the government announced Georgia was freezing its EU membership bid, that mass daily anti-government demonstrations broke out.

Tsaro says that throughout this period, they continued to speak via Facebook Messenger. But on 29 November, Archil went offline — that’s how she realised he had been arrested.

At the time, she didn’t even know his surname, as it was not listed on his social media accounts, meaning she could not call the police to find out his whereabouts. After a lot of searching and asking around, she confirmed his arrest. She decided to attend his trial.

In the early hearings, Tsaro remembers that not many people showed up. It was only in court, waiting for the judge to appear, that she managed to have her first conversation with him since his arrest.

‘I was sitting close [to him], it was a small room, so we had a chance to chat. That’s when I asked him about his grandmother. I didn’t know that his grandmother had passed away too. This was the person who had raised him’, she says.

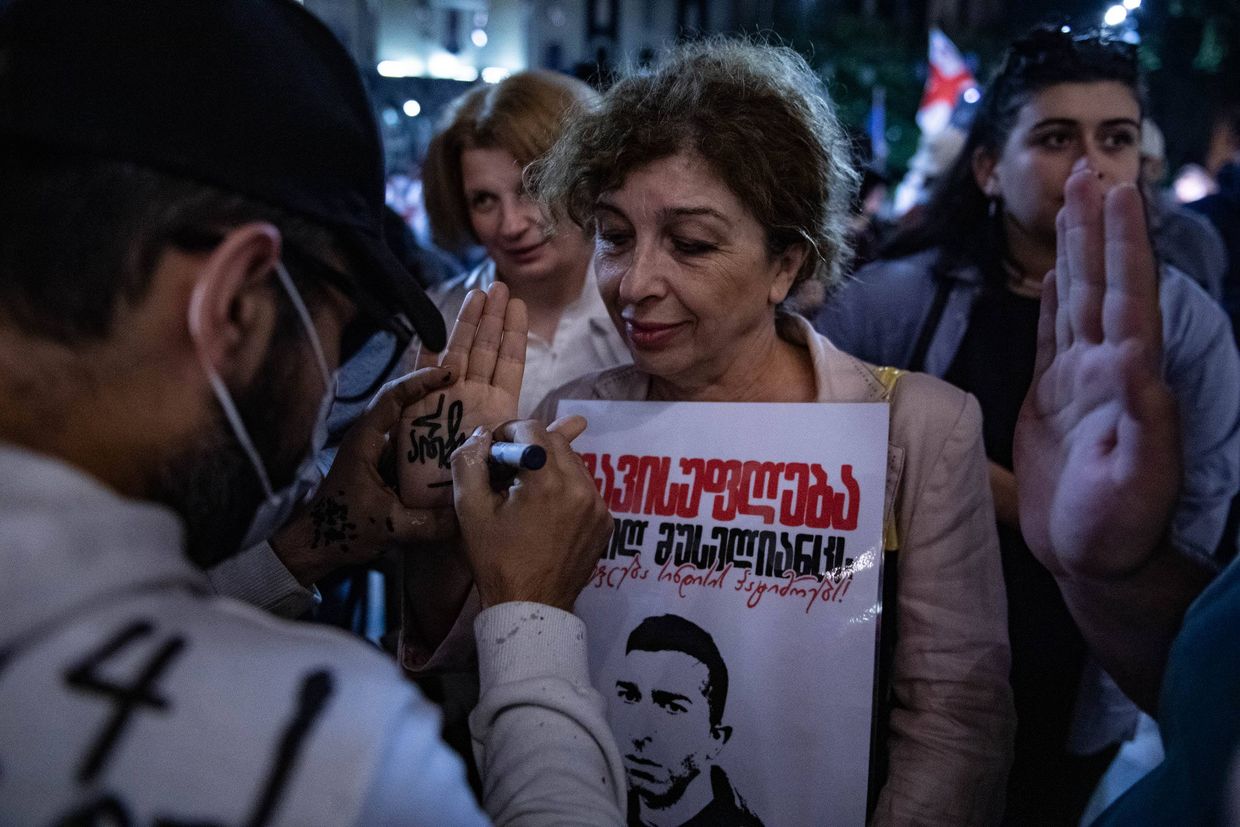

When the mothers of other prisoners started carrying banners with photos of their sons, Tsaro made her own banners for Archil. She says she was nervous at first, because she didn’t know how the other mothers would react. She approached them and asked to take a photo together with them with their banners.

‘It was the mother of Zviad Tsetskladze who accepted me first’, Tsaro recalls. Zviad was sentenced to 2.5 years in jail in September 2025 on charges of organising and participating in group violence.

‘She doesn’t remember it properly now’, Tsaro continues, ‘but I remember it vividly — when she learned that Archil was an orphan and that I was carrying his photo, she came to me and hugged me. I told her I felt awkward about the whole situation, but she told me to be proud, to support Archil. She comforted me like that.’

Soon after, Archil began writing letters from prison telling her how happy he was that someone was raising their voice for him.

‘When he wrote to me the first time, I was so happy. And then he called. The first call — it got me so excited — I was running happily through the house. He was thankful for what I was doing for him’, Tsaro says.

Since then, their communication has become even more intensive — they write letters to each other every day. He now addresses each of his letters to her with ‘Mum’, something Tsaro feels emotional about, as she says he had never had the chance to call anyone mum.

‘Sometimes I feel like he is addressing his own mother through these letters, I don’t know’, she says.

After the verdict, Tsaro says that Archil wrote to her that he ‘loved me very, very much. He said: “You are honestly a very honourable mother, my mother” ’.

‘If we don’t fight, we will lose our homeland’

Despite their connection, difficulties arose when Tsaro tried to visit Archil in prison, as they are not officially related. Despite a date eventually being set, she was denied admittance at the last minute.

‘He called me, then. It was a difficult call and was followed up with quite a heavy letter too. He was very disappointed that we couldn’t meet. Clearly he wanted to talk about his life. So he had to do it in writing after that. This is how I learned that the grandmother who raised him was not his actual grandmother’, Tsaro says, noting that the grandmother had also been an orphan.

Over time, through letters, his friends, and attending court hearings, Tsaro says she began to really know Archil.

‘He is a smart, warm, and loving person. His friends say so too. There are these girls who remember how he helped them during protests — during dispersals. He is kind and trusting — also brave’, she says.In a letter published in the first edition of a prison newspaper delivered by the mothers of jailed protesters — which they have been distributing across Georgia over the summer — Archil wrote that he was born and raised in the south Georgian village of Kazreti.

‘I had a very difficult life as a child. I was six months old when my parents died. I was raised with the thought that my whole life I had to fight and learn’, he wrote.

Tsaro learned that Archil first became politically active during a protest in his hometown in 2014 over the destruction of the prehistoric Sakdrisi Gold mine. He was around 20 years old at the time.

The mine, once touted as the ‘oldest gold mine in the world’, was blown up in December 2014 by a private mining company after months of protest over its cultural heritage status. The explosion occurred the day after the Ministry of Culture removed the mine’s status as a protected cultural monument.

‘After that he was more active at protests. He wanted to play his part in the resistance for his homeland’, Tsaro says.

Writing about Kazreti, Archil recalled that after Sakdrisi was destroyed, he realised that something had to change and that he could contribute to this change.

‘My whole life, I have stood beside those who fight injustice, as I have faced a lot of injustice myself’, he wrote in a letter.

‘If we don’t fight, we will lose our homeland. I and other hostages of the regime are proud that we are being punished for wanting a better future for our children’, he wrote.

After he finished school in Kazreti, Archil moved to Tbilisi, where he started working to feed himself and his elderly grandmother — he never made it to university.

Once imprisoned, Archil finally had free time, which gave Tsaro the idea that he should try to pass the national exams from prison and continue his education.

‘The thing is, he is in prison and alone, and he needs support — I try to make this easier for him, and I think I’ve managed it somewhat, especially after he was successful at the exam and enrolled at university’, Tsaro says.

Tsaro went to each of Archil’s exams to cheer for him from beyond the walls of the building. Archil passed them all and will begin studying law at the Georgian Technical University this autumn — remotely from behind bars.

A journey to where Archil’s story began

Tsaro has two children of her own, both of whom are married with their own families. She says they are very supportive, but that they are also worried for her.

‘When I told them about organising this demonstration here in Kazreti, my son told me, “Oh, so you’re even an organiser now; I’m afraid I will have to visit prison to hand products to you”. But I told him that I have so many people supporting me now, I would be fine even in prison’.

Tsaro often goes with the family members of other imprisoned protesters to distribute newspapers featuring the letters of those jailed. She has found that her relationship with Archil has gained the pair of them some notoriety.

‘Even though I was strong on the day of the verdict, emotions still piled up. There was one woman who recognised me when we were in Imereti. She hugged me and we cried together’, Tsaro says. ‘This support and warmth I get from people during these trips helps me a lot — it gives me strength and convinces me that I should continue doing what I do’.

Going to Kazreti, however, Tsaro did not have high hopes. It’s a small community, she says, where a lot of people are employed by the gold mine and are scared to lose their jobs. Tsaro still hoped, however, that she would meet Archil’s neighbours, classmates, or teachers who would be more positive.

‘I feel like I’m visiting his childhood’, she says. ‘That’s why I brought a lot of toys and other things to give to children in his name.’ She ended up leaving the items at the local church for children in need.

As expected, people were more restrained in Kazreti than in other places. Still, one of Archil’s teachers recognised her. While scared to show public support towards anti-government protesters over fears of losing his job, he met Tsaro warmly, asking her to send his warm regards to Archil.

Now, almost a year since his arrest, Tsaro says she loves Archil as much as she loves her country.

‘Archil is Georgia for me, not just a child, but I have such a feeling that it is impossible not to love Georgia, our homeland’, Tsaro said during a protest outside the Supreme Court on 29 August.

When talking about the future, Tsaro notes that she is more optimistic than Archil. However, they both think Georgia returning to its democratic path will take a long time.

‘But I still hope that they [Georgian Dream] will fall soon’, she adds.

![Baia Margishvili standing in central Tbilisi with a sign reading: ‘The Prosecutor’s Office [is] a punitive squad. How many more innocent people will you put in prison?’ Photo: Mariam Nikuradze/OC Media.](/_next/image/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fassets.bucket.fourthestate.app%2Foc-media-prod%2Fcontent%2Fimages%2F2026%2F02%2Fcalls-for-sanctions-and-raids-19-10-25-48.jpg&w=3840&q=50)