A still-forming group in parliament led by former Georgian Dream member Eka Beselia could upset the political landscape in Georgia. With 2020 parliamentary elections on the horizon, this new group poses a potential threat to both billionaire former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili’s ruling party as well as the main opposition.

A still-forming group in parliament led by former Georgian Dream member Eka Beselia could upset the political landscape in Georgia. With 2020 parliamentary elections on the horizon, this new group poses a potential threat to both billionaire former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili’s ruling party as well as the main opposition.

On 27 February, Zviad Kvachantiradze became the latest member of Georgian Dream to announce his departure from the party.

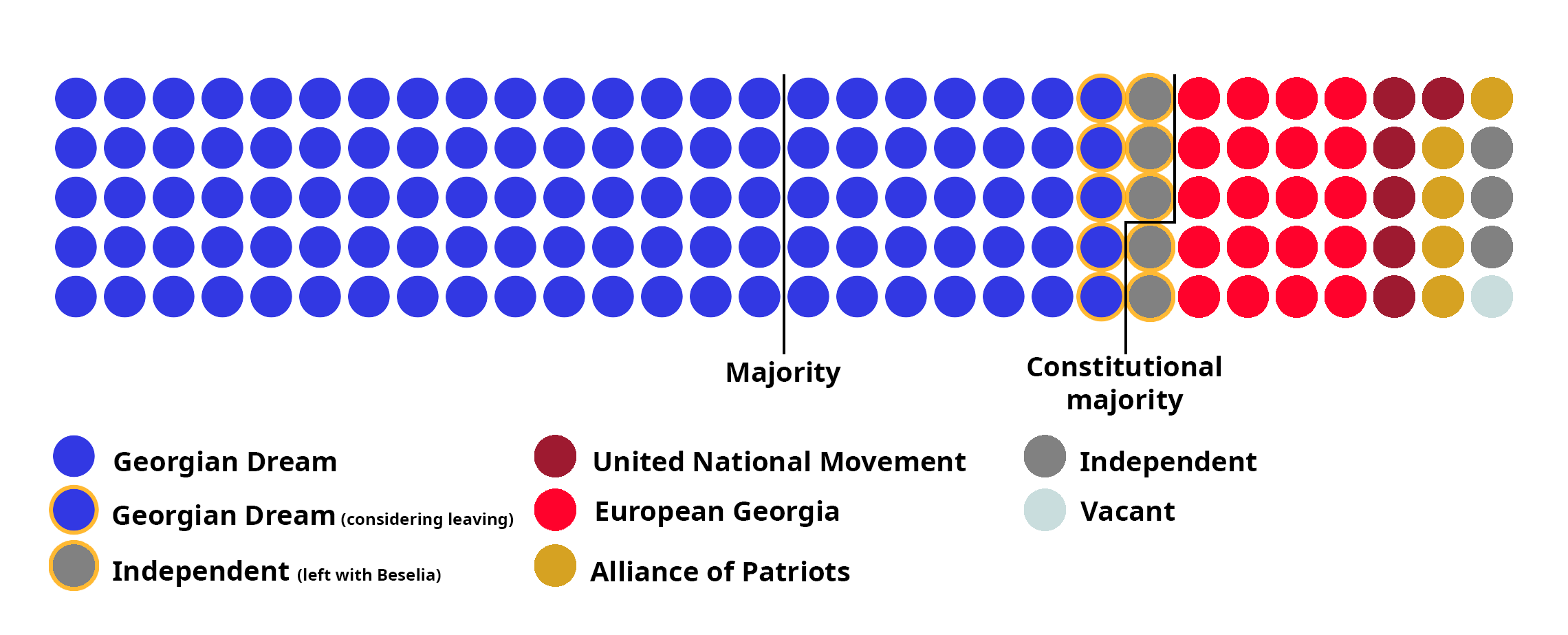

Georgian Dream, which, following the 2016 election, held 115 of 150 seats, has lost five members within the last few days, also losing, on 22 February, the 113 seats needed to make constitutional changes.

Most of the ex-Dreamers have consolidated around Eka Beselia, a lawmaker responsible for this latest challenge to Georgian Dream’s rule.

In December, Beselia publicly attacked her party leader and Speaker Irakli Kobakhidze for rushing the confirmation of 10 Supreme Court justices.

Insisting that the judicial nominees had served the former ruling United National Movement party (UNM) in making politicised judgements, eight Georgian Dream dissenters proposed a bill to introduce a five-year moratorium on lifetime appointments to regional and appeal courts.

The bill was rejected, though only 17 Georgian Dream members actually voted against it — the majority just abstained. However, the fact that those who voted in favour of it came from different political backgrounds — 17 from Georgian Dream, 26 from the opposition parties, and two independents — is something to pay attention to.

Probably more to leave

Beka Natsvlishvili, deputy chair of Social Democrats for the Development of Georgia party (SDD), was among those who left Georgian Dream.

In parallel to Beselia’s initiative, Natsvlishvili lodged his own alternative bill to the current pension scheme. He proposed a merit and experience-based, ‘pay-as-you-go’, accumulated pension scheme, with the principle of ‘intergenerational solidarity’. Natsvlishvili’s bill was also voted down by his own party, causing him to leave on 22 February.

Gia Zhorzholiani, the leader of the Social-Democrats, indicated on 26 February that he and other social-democratic faction members were likely to follow.

The Social-Democrats are a subgroup of the Georgian Dream majority.

Zhorzholiani and Natsvlishvili agreed with Georgian Dream dissenters on the judicial reforms, but they stressed that the breaking point for them was the rejection of their pension and housing policy proposals.

Left-leaning MPs of the formally centre-left Georgian Dream party have been bitter for some time. Georgian Dream’s decision not to axe a constitutional ban on tax hikes was not the least of their grievances.

If the other Social-Democrats follow Natsvlishvili, the ruling party will lose six more members, leaving them with only 104 MPs.

Who is Eka Beselia?

Ivanishvili hired Beselia, a lawyer and an opposition figure since 2006, in October 2011. He did so after finding himself stripped of his Georgian citizenship days after announcing his plans to sweep Mikheil Saakashvili and his UNM Party from power.

She was one of the original founders of the Georgian Dream party. By chairing the parliament’s human rights and legal affairs committees, Beselia remained an influential party member until Ivanishvili announced the end of his political hiatus in 2018.

Ivanishvili’s comeback eventually led to Beselia leaving the Party’s Political Council.

Beselia failed to convince her party leader to not go forward with the lifetime appointments of judges. Ironically, one of the judges had seven years earlier ruled against Ivanishvili regarding the loss of his citizenship.

In an interview on 5 February with TV Pirveli, Kobakhidze suggested that the past rulings by the aspiring Supreme Court nominees were down to political pressure, which was not the case anymore.

In the same interview, Kobakhidze assured the public that ‘those [judges] who did massively bad things then, do good things now’.

Georgian Dream-judicial clan alliance

Georgian Dream has largely retained their source of legitimacy and political identity by portraying themselves as a force righting the wrongs of Saakashvili’s rule, and preventing his UNM party from regaining power.

Nevertheless, Kobakhidze’s statement was not the first explicit nor surprising departure from the party line that promised to ‘restore justice’ for the victims of abuses of judicial power during the UNM years.

In 2013, soon after coming to power, Georgian Dream reached out to several influential judges loyal to the previous government and helped them consolidate a judicial group under the High Council of Justice (HCoJ), a constitutional body that oversees the judiciary.

The parliamentary opposition groups and individual Georgian Dream members in power failed to make a strong case against Levan Murusidze, the judge responsible for one of the most scandalous rulings — that of the Sandro Girgvliani murder case — being elected as HCoJ’s secretary.

With this mutual understanding, Georgian Dream gradually dropped their idea of looking into cases of grave miscarriages of justice that had taken place before 2012. In the meantime, the judicial group, dubbed by critics as a ‘clan’ or a ‘brotherhood’, strengthened the party’s position in the HCoJ.

Over the years, the opposition UNM and European Georgia parties have become more critical of the cooperation between Georgian Dream and the group of judges they used to control. They joined civil society groups in criticising the ‘clan’, which had renewed its position of power.

This criticism could have suggested to Beselia and her allies that it was best not to delay their departure, as their chances of regaining power in the party were fading and they could miss the last chance to gain a role in politics beyond Georgian Dream.

A new parliamentary opposition?

Beselia’s dissent could complicate things for both the ruling party and the parliamentary opposition.

If Beselia is successful in building what she has called a ‘political platform’, Georgian Dream might ultimately lose their favourite arch-enemy — the UNM and European Georgia — as the main oppositional force.

According to current parliamentary regulations, even If Georgian Dream keeps 109 MPs, European Georgia’s status as the parliamentary minority might be in jeopardy.

Currently, a parliamentary group or groups can form a minority provided they unite over half of the MPs that are outside the majority.

European Georgia currently holds 20 seats, and none of those fleeing or considering fleeing Georgian Dream are expected to join them or the six-member UNM faction.

MPs alienated from Georgian Dream ran on a platform that condemned former President Saakashvili’s legacy and promised a fair court system. Hence, European Georgia and UNM, both associated with him, would be too politically radioactive for them to ally with. At least, publicly.

Goals and grievances

In the short term, groups critical of Georgian Dream are expected to pursue two main goals.

The first is a suggestion voiced by various civil society groups and politicians, to come up with a measure to prevent influential judges at the HCoJ from appointing judges for life, or remove the ‘clan’ from the HCoJ entirely.

The second goal, voiced by a growing coalition of opposition parties, is transitioning the country from a single-constituency (majoritarian) system to a fully proportional one for parliamentary elections. With the latest constitutional amendments, Georgian Dream delayed this proposal until 2024.

This is the immediate political setting that Beselia and her allies will have to navigate.

Their success will depend on how they respond to grievances related to the Georgian Dream government they were previously associated with, and whether or not they agree that Ivanishvili is more of a threat than European Georgia, UNM, and the civil society groups they have previously called enemies.