Over the past two months, one of the most heated and widely discussed issues on Armenia’s domestic agenda has been the intensification of tensions between the state and the Armenian Apostolic Church.

This latest escalation began on 29 May, when Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, during a regular cabinet meeting, commented on the need to establish standards for churches and remarked that ‘our churches have been chulanised’ — or turned into storerooms.

His statement prompted reactions from members of the clergy, and from 30 May, Pashinyan began responding to these reactions via a series of increasingly hostile Facebook posts targeting the country’s spiritual leadership. His language — at times unorthodox — sparked widespread public debate. The digital confrontation mirrored the real-life tensions that were growing by the day.

The next escalation came on 17 June, when Russian–Armenian businessperson and philanthropist Samvel Karapetyan issued a public statement in support of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

‘A small group, forgetting the history of the Armenian nation and the millennia-old history of the Armenian Church, has launched an attack on the church and the people’, he said. ‘I have always stood by the church and the people. If the politicians fail, we will have our own way of participating in all this’.

The following day, Karapetyan’s house was raided and he was remanded into pre-trial detention.

Also on 17 June, a criminal case was initiated against Archbishop Mikael Ajapahyan, Primate of the Shirak Diocese, for stating that a military coup was ‘necessary’.

On 25 June, while Pashinyan was on an official visit to Turkey, the National Security Service raided the homes of several opposition figures, including Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan. Galstanyan was arrested and later remanded into custody as part of an investigation into alleged plans to ‘carry out terrorist activities and seize power in the Republic of Armenia’.

On Facebook, Pashinyan wrote: ‘A crime that was being prepared against the security and stability of the Republic of Armenia has been uncovered. I want to thank all representatives of the law enforcement system’.

These events have ushered the church–state standoff into a new and more consequential phase — raising the deeper question: how did it all begin?

The origins of the crisis

Signs that the relationship between the government and the Armenian Apostolic Church were growing tense emerged almost immediately after Pashinyan came to power in the 2018 Velvet Revolution.

Later that year, a civic initiative called New Armenia, New Catholicos began to emerge, demanding the resignation of Catholicos Karekin II. Members of the movement accused the catholicos of various abuses, of applying undue internal pressure within the church, and of having ties to criminal and oligarchic networks. They organised a series of protests — from rallies to sit-ins — including demonstrations in front of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, the seat of the Armenian Church.

The initiative also became an actor in the digital space via a Facebook page bearing the same name. Over the years, the page remained consistently active, regularly publishing ‘revelations’ and accusations against the church leadership, and often repeating calls for the catholicos to resign.

These posts mirrored the movement’s public rhetoric and helped amplify its messaging through social media. The page has never ceased its activity. On the contrary, in the context of renewed tensions between church and state, it reactivated with greater intensity, reiterating previous accusations and demands for the catholicos to step down.

The page has often served as a platform for defrocked cleric Khoren Hovhannisyan, one of the movement’s most outspoken figures. During the latest period of heightened tensions, Hovhannisyan became a prominent voice not only on Facebook, but also on Public Television, where he featured as a major critic of the catholicos.

In his televised appearances, Hovhannisyan repeated a number of serious accusations against Catholicos Karekin II, including that he was an agent of Russian intelligence tasked with organising a coup, that he was responsible for the suspicious death of Catholicos Karekin I, that he has fathered children with multiple women despite his monastic vows, and that he was the mastermind behind the alleged violent plans attributed to Archbishop Galstanyan and Archbishop Ajapahyan.

After the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, the conflict deepened, as the church increasingly issued public criticisms of the government — especially on issues related to national mourning, military service, and social unity.

A new phase began in April 2024 as public and political tensions flared surrounding the delimitation and demarcation of the border with Azerbaijan in the northern Tavush Province.

Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan, head of the Tavush Diocese, launched a campaign of civil disobedience and protest known as the Tavush for the Motherland movement. This movement, now known as the Holy Struggle, united thousands, who began marching from Tavush to Yerevan on 4 May 2024, culminating in a large rally in the capital’s Republic Square on 9 May.

Although Galstanyan stated that the movement had no political ambitions, the political demands voiced during the rallies — including calls for Pashinyan’s resignation — brought together various opposition forces and figures. In his speeches, Galstanyan emphasised the ‘moral and spiritual foundation’ of the movement, though the political undertones were clear. Galstanyan described the movement as ‘national-liberation’ in nature, adding that ‘its ultimate solutions are political’. Addressing Pashinyan directly in one speech, he declared: ‘You no longer hold any form of power in the Republic of Armenia’.

‘With your resignation, you will return the stolen spirit of our national celebrations to the people. As they say in Shamshadin, the show must go on’, he said.

Elsewhere, Galstanyan stated that ‘the tricolour has defeated black-and-white, and very soon spiritual Armenia will triumph over the so-called “new Armenia”, giving birth to a renewed country with a new vision and a new march’.

Later, he even declared that he would be ready to run as a ‘people’s candidate’ for prime minister if called upon to do so.

At the same time, the catholicos publicly blessed the Holy Struggle movement, leaving no doubt as to his support. This marked a pivotal moment in which spiritual leadership overtly merged with political activism — a shift many interpreted as a redefinition of church–state boundaries under Pashinyan’s tenure.

Over time, the erosion of trust between the two institutions was reflected not only in official statements but also in shifting rhetoric and the use of social media as an arena of confrontation.

At a press conference in May 2024, Pashinyan directly addressed the role of the catholicos in recent political developments: ‘It is obvious that today the Catholicos of All Armenians is leading a political movement — that’s very clear’.

However, in January 2025, during a meeting with representatives of the Armenian community in Zurich, Pashinyan separately addressed the long-standing demands of the New Armenia, New Catholicos movement, emphasising that he had stated from the beginning that the government had no role in the catholicos’ election process.

Pashinyan said that the initiative had been launched during the revolution by former clergymen and, although many believed the movement was orchestrated by the government, that was not the case.

‘If we had been behind the process in 2018, I believe you all would agree that the result would have come quickly. But it was never part of our political agenda’, Pashinyan stated.

The digital frontline

The latest phase in the church–state standoff has been defined by Pashinyan’s posts on Facebook — in terms of their volume, content, and especially their vocabulary. These posts show that politics is breaking into the spiritual sphere in a fully mediatised way.

Pashinyan’s Facebook activity on matters of spiritual leadership have amounted to more than political signaling — it has directly questioned the moral legitimacy of the church. For example, in one 30 May post, Pashinyan asked: ‘What happens when it turns out that a celibate cleric has violated his vow? He is stripped of his office, his rank, and his vestments’.

In an analysis published on his Telegram channel, political analyst Hakob Badalyan characterises this not as mere moralising but as an attempt to blackmail — a message intended to influence internal church decisions. When these signals come directly from the head of government via social media, they testify to a deepening mediatisation of the church–state debate. Church authority is now contested not only in sermons and ecclesiastical statements but in politicians’ direct online communications — often without any intermediary.

In the very next paragraph of the same post, Pashinyan asserted: ‘The state belongs to the people. The church belongs to the people. We have returned the state to the people’.

Here, he extends the same populist legitimacy claim to the church — demanding that spiritual authority, like political power, rest on popular mandate.

Although these posts focused on canon law, public attention was drawn to Pashinyan’s sometimes uncharacteristically coarse language.

One of his early posts — interpreted as a reaction to the clerical outrage that came from his 29 May post — read:

‘Dear Bishop, go on and keep banging your uncle’s wife — what do you want from me?’

In another post, Pashinyan accused a clergyman of escorting Holy Struggle ‘tourists’ to hotels outside of the rallies, asking: ‘So, who exactly are we fighting — the church?’

After the spokesperson of the catholicos claimed publicly that Pashinyan had been circumcised, Pashinyan responded provocatively: ‘I’m ready to meet with Ktrij Nersisyan [Karekin II] and his spokesperson and prove otherwise’, implying he would show his penis to the catholicos.

He also wrote: ‘The House of Christ — where the Only-Begotten descended through the Holy Spirit — is now occupied by an anti-Christian, adulterous, anti-national, and anti-state group. That house must be liberated. And I will lead the liberation’.

Political analyst Hakob Badalyan tells OC Media that such rhetoric is not merely reactive or stylistic.

‘Of course, harsh rhetoric has become a general trend in Armenia’s political culture, but in my view, Nikol Pashinyan is not just giving in to that trend — he is deliberately using this kind of language. He knows his electoral base well and understands its demand. That base continues to consume the persona of “oppositionist Pashinyan”, and he maintains that supply through his tone and behaviour’.

These outbursts have added a volatile emotional layer to an already high-stakes institutional standoff. For international observers, they have also made the conflict appear unusually raw — shaped less by formal political discourse and more by spectacle, personal attacks, and social media escalation.

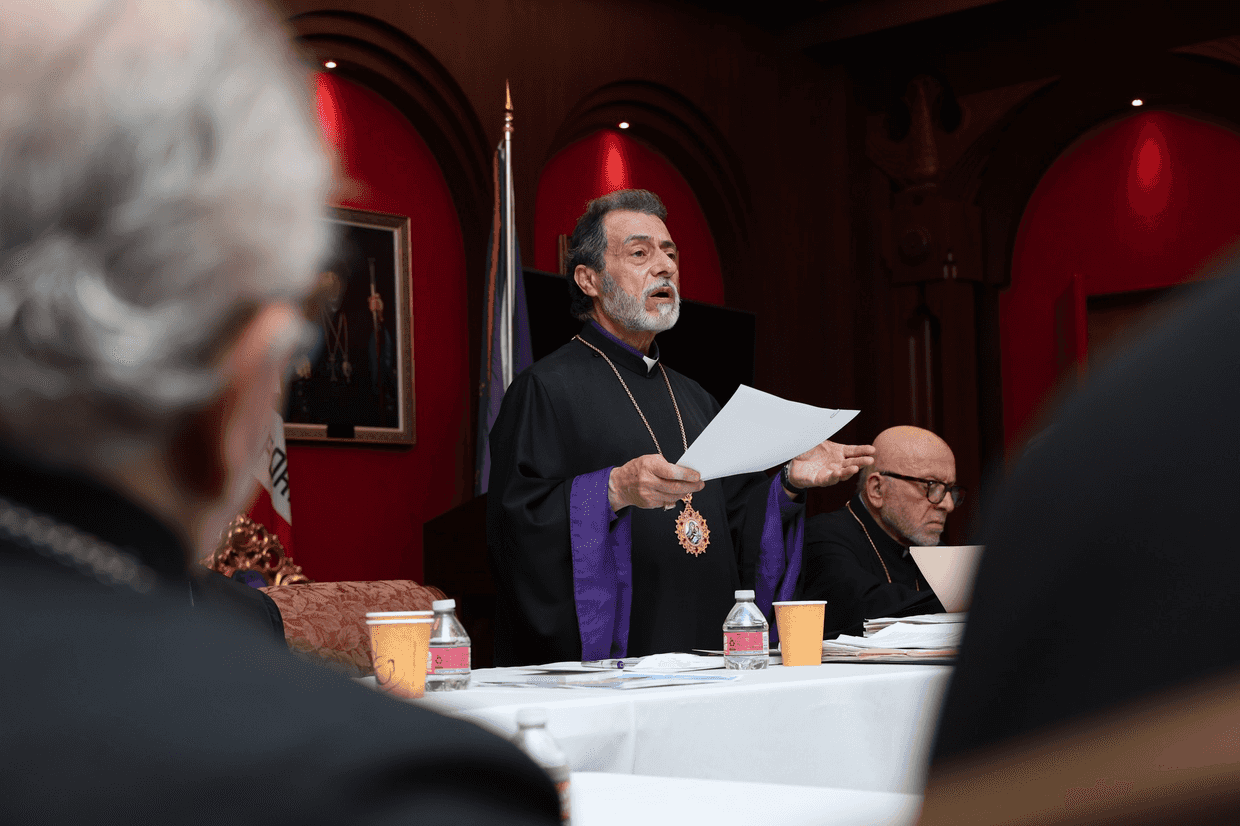

On 2 June, the Supreme Spiritual Council of the Armenian Apostolic Church, an advisory body of senior clergy chaired by the cathalicos, issued a statement condemning Pashinyan’s ‘anti‑church campaign’ as a threat to the state.

‘His scattergun, abusive posts trample basic rules of civility, violate fundamental human rights, gravely offend believers’ religious sentiments’, the statement said.

‘The head of government’s anti‑church conduct carries destructive consequences and poses a threat to Armenia’s statehood and our people’s unity in both the homeland and the diaspora […] church matters are governed by ecclesiastical rules and are beyond the authority of state and political figures’.

Commenting on this statement, Badalyan — in an analysis shared on his Telegram channel — praised its ‘measured tone’ and suggested it may reflect a deliberate effort to avoid further mutual attempts at blackmail.

‘For the church to act as a true subject in this process, it must transcend emotional reactions — however prudent. After nearly two millennia, the Armenian Apostolic Church has endured not through emotional outbursts, but through institutional sobriety and strategic vision’, Badalyan wrote.

Badalyan further observed that in this phase, the church’s real rival is not political power, but time itself — that is, the consequences of failing to address new social and moral challenges in a timely way. He added that, rather than losing public authority as a result of government attacks, the church may actually be gaining — at least in terms of its opportunity to engage with society.

‘It depends on how well the church can make use of that opportunity: whether it will be squandered in the short term, or used wisely to strengthen the church. If not, there is a risk that — through miscalculation — it may be co-opted by political forces and thus wasted once again’, he said.

On 28 June, Pashinyan posted again, calling to ‘end harassment and hybrid targeting in the public‑political arena’ from a chosen date forward.

Later that same day, Facebook briefly blocked one of his more uncouth posts about the catholicos and senior prelates, which contained particularly inflammatory language. In it, Pashinyan addressed Catholicos Karekin II directly, writing: ‘Ktrij Nersisyan, so you’re now relying on a few licentious “clerics”?’

He continued with explicit accusations: ‘Why haven’t Zareh [Father Zareh (Mesrop) Ashuryan], the so-called priest, and Samvel Khachatryan [Archbishop Arshak Khachatryan] — who has not only defiled his own family but also yours, and you personally know it — been defrocked yet?’

Why did these developments unfold so intensively on Facebook?

Badalyan told OC Media that Facebook has become a means to serve multiple agendas — including Pashinyan’s own political survival ahead of the 2026 parliamentary elections.

‘Pashinyan’s political persona is sustained within his electoral base by exactly this combative style and tone. He uses these online tactics to satisfy his electorate’s appetite in the heat of a pre‑election campaign’, Badalyan said.

Badalyan suggested that the confrontation was unfolding within a pre-election logic.

‘I believe this is a confrontation developing in the context of electoral strategy, where Pashinyan is trying to solve at least two issues’, he said.

‘First, to establish maximum control over the church, which carries significant public influence and national importance. Second, the church has traditionally maintained close ties with major capital holders — as we saw with the involvement of Samvel Karapetyan and the direct targeting of him. Through his actions against the church, Pashinyan is attempting to secure a strategic advantage over economic elites in the run-up to elections’.

In this context, religious scholar Vardan Khachatryan offers a perspective rooted in the institutional nature of the church:

‘The Armenian Apostolic Church is fundamentally different from the country’s political authorities. Governments are local phenomena — they represent the Republic of Armenia. The Armenian Apostolic Church is a global institution, with a broader follower base spread across the world’, Khachatryan told OC Media.

According to Khachatryan, attempts by the state to interfere in church affairs lack constitutional grounding and may even prove counterproductive.

‘This kind of rhetoric doesn’t strengthen the government — it erodes its core electorate, raising doubts and weakening trust from within’, he said.

Badalyan, however, views the situation more as an opportunity than a blow to the church’s authority. He emphasises that the main issue is how the church will use this opportunity.

‘Yes, there is a crisis, and it is serious, full of risks and challenges for society and the state. However, every crisis also contains potential — especially when we are dealing with attacks from a government with significantly low approval ratings against an institution that enjoys high public trust’, Badalyan noted.

This article was translated into Russian and republished by our partner Jnews.