When the Azerbaijani government failed to take care of the civilians staying near the front during the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, it was volunteers who stepped in. Their sometimes secret work continued despite danger, injury, and personal tragedy.

When the war began, Barda resident and career peacebuilder, Ulviyya Babasoy fell into a deep depression. She told OC Media she first began volunteering because she felt she had to somehow make herself feel useful.

At the first, her work was sporadic; together with a group of friends, she would ferry medical aid to clinics and basic supplies, such as food and blankets, to soldiers that they had contact with. But as the war continued, the scope of her work began to change. A flood of displaced people was entering Barda, fleeing the shelling in Aghdam and Tartar — areas much closer to the front.

‘All of the schools, kindergartens, some cafes and wedding halls, as well as trucks on the sides of the road were filled with people’, she recalled.

Where states fail to provide for or protect their citizens, it is volunteers, often risking life and limb, who step in — bridging the gap between governments and humanitarian agencies and ensuring that as few people possible fall through the cracks.

The government of Azerbaijan has indicated that some 40,000 Azerbaijanis were temporarily displaced during the war, and where the government could not take care of them, volunteers like Ulviyya stepped in.

Nearer to the front

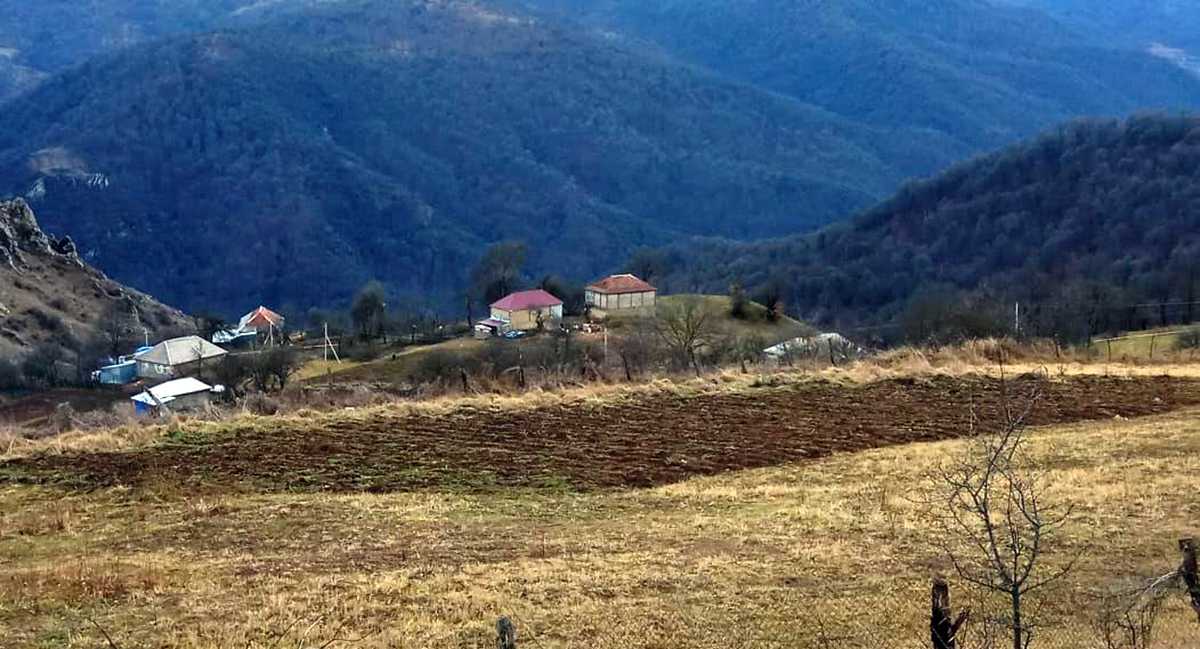

In the village of Benovsheler, just five kilometres from the front in the Aghdam region, Maya Guliyeva turned her home into a warehouse providing aid and supplies. After the war began, because of the close proximity to the fighting, Maya and her mother were the only women left in the largely empty village.

Maya not only distributed aid that she gathered as donations, but also prepared hot meals. Herself displaced during the first Nagorno-Karabakh war, she told OC Media, that as ‘a woman who knew firsthand the hardships of war’ she could not bring herself to leave her fellow villagers.

Due to regular shelling, nearby petrol stations, grocery stores, and other shops closed. The few villagers who remained, as well as soldiers stationed nearby, came to Maya for socks, blankets, rain boots, medication, food, petrol, and other basic supplies.

The aid she gave out, she said, did not have to go through the same ‘complicated and time-consuming’ bureaucratic process that aid from the authorities was mired in. As she described it, soldiers, for example, would have to present official documents to municipal authorities to receive goods. These documents, which specified the quantity and purposes of the aid, would then be processed, and only then — if approved — would the aid be delivered.

Many, Maya said, were turned away.

On 19 October, a shell hit Maya’s home while both she and her mother were inside. Shrapnel embedded itself in her mother’s arm and tore through her leg — despite these injuries, the two continued their work.

Only prepared to fight

Sanubar Heydarova, who worked to evaluate and provide for the needs of the civilians living in shelters in Goranboy and Barda told OC Media that the government may have been very well prepared for fighting the war, but it was not prepared for taking care of the civilians behind the frontline.

‘Maybe the state thought that they would advance very fast and these areas wouldn’t be affected so much. But during the war, I was angry and I was thinking that nobody cares about the people’, she told OC Media.

She described a situation in which, there was no warning system in place during the shelling. There was a lack of doctors and medical specialists and an acute lack of space for the displaced, with some families who were relocated to schools forced to sleep on students’ desks.

Many did not have access to showers, baths, and similar basic amenities for personal hygiene.

‘And that was it. No doctors, no sirens before shelling, not enough space in the basements that were too humid to stay in long term’, Sanubar said. ‘If the war was prepared for and the schools have been emptied to be turned into shelters, how come there were no conditions to bathe for weeks?’

According to Sanubar, the displaced population also had difficulty obtaining vital medication. While they were technically supposed to procure from their local administrations, they often could not locate them — as the administrations themselves relocated during the war.

A lack of care for farm animals also indirectly caused a number of deaths. Sanubar recalls a number instances when people would leave their shelters to feed their animals — only to perish in renewed shelling. ‘In my opinion, people should have been provided with vehicles to get their belongings and animals out of the conflict zone’, she said.

Few international organisations helped with the humanitarian efforts, except for the Red Crescent (ICRC). But, Sanubar said, she believed that even the ICRC was not ready for this scale of destruction.

Despite these circumstances, when Sanubar’s group — six Bakuvians, in total — requested that the government allow them to do volunteer work in the region, they were rebuffed. Sanubar and her colleagues moved ahead regardless.

They had to work in relative secrecy, strictly avoiding any contact with representatives of the state. The authorities did not find out that they were there, as they worked directly with locals.

After the war

After the signing of the tripartite peace declaration, Ulviyya Babasoy and her group of volunteers continued to provide aid to demobilised soldiers as well as to families near the front. Indeed, Sanubar and Maya have also continued their work.

‘They don’t ask us for anything but attention. They don’t want to be left alone and forgotten’, Ulviyya said.

Despite taking such time, effort, and risk to help others — even evading the law when necessary — these volunteers also suffered personal tragedies.

Maya’s son Khalid, who had settled in Barda with his wife and 10-month old child, volunteered to fight on 28 October, the day after a cluster munitions strike hit the city killing 21 civilians — the highest daily civilian death toll during the war. He died on 4 November, six days before the peace declaration was announced.

Ulviyya lost a close friend during the war; she says she has still not recovered, and the fact that Azerbaijan won the war does not make the pain go away.

‘Karabakh is very important for me, we have to return there, yet I didn’t want the war’, she said. ‘In war, there is not really a winning side.’

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status