Nearly half of Georgians’ report negative impacts on their psychological health because of the pandemic, and women have been one of the worst affected groups.

Although the pandemic has been primarily a physical health crisis, it has also had large effects on people’s mental health. The pandemic altered the way people study, work, and travel — as well as almost every other aspect of everyday life.

Research from other countries has shown the pandemic has led to a significant rise in symptoms of anxiety disorder and/or depressive disorder.

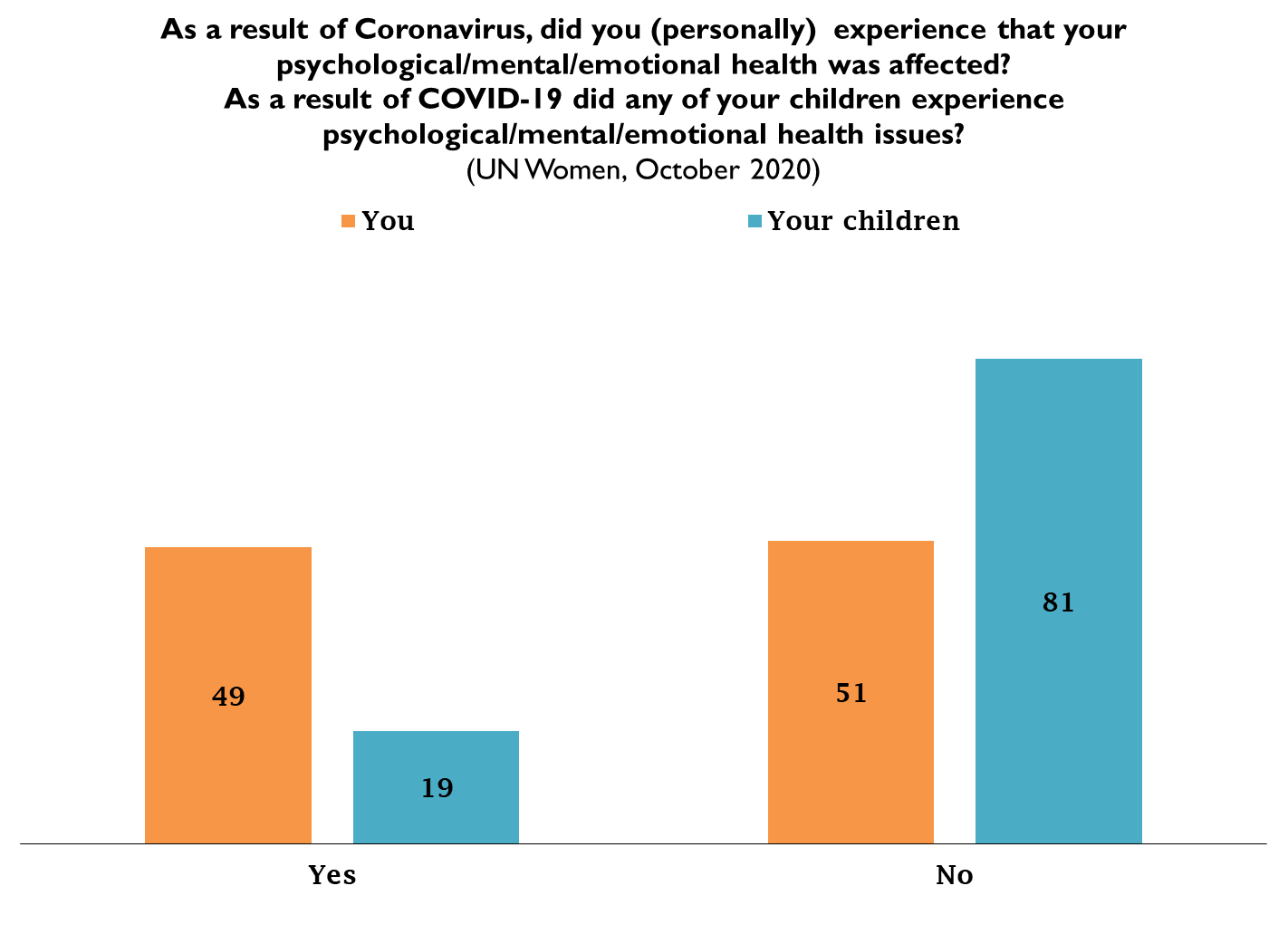

The Rapid Gender Assessment survey CRRC-Georgia conducted for UN Women and UNDP in October 2020 asked the adult population of Georgia if their own or their children’s psychological health had been affected as a result of the Coronavirus.

The results showed that women were significantly more likely to experience psychological health challenges as were people who experienced delayed access to services and significant changes to their everyday lives.

Unsurprisingly, given the uncertainty and stress involved in the pandemic, large shares of Georgians report they or their children experienced negative psychological outcomes from the pandemic. Data from the Rapid Gender Assessment survey shows that COVID-19 negatively affected around half of Georgians’ psychological health. In contrast, only 19% of Georgians who have children report that their children experienced psychological issues.

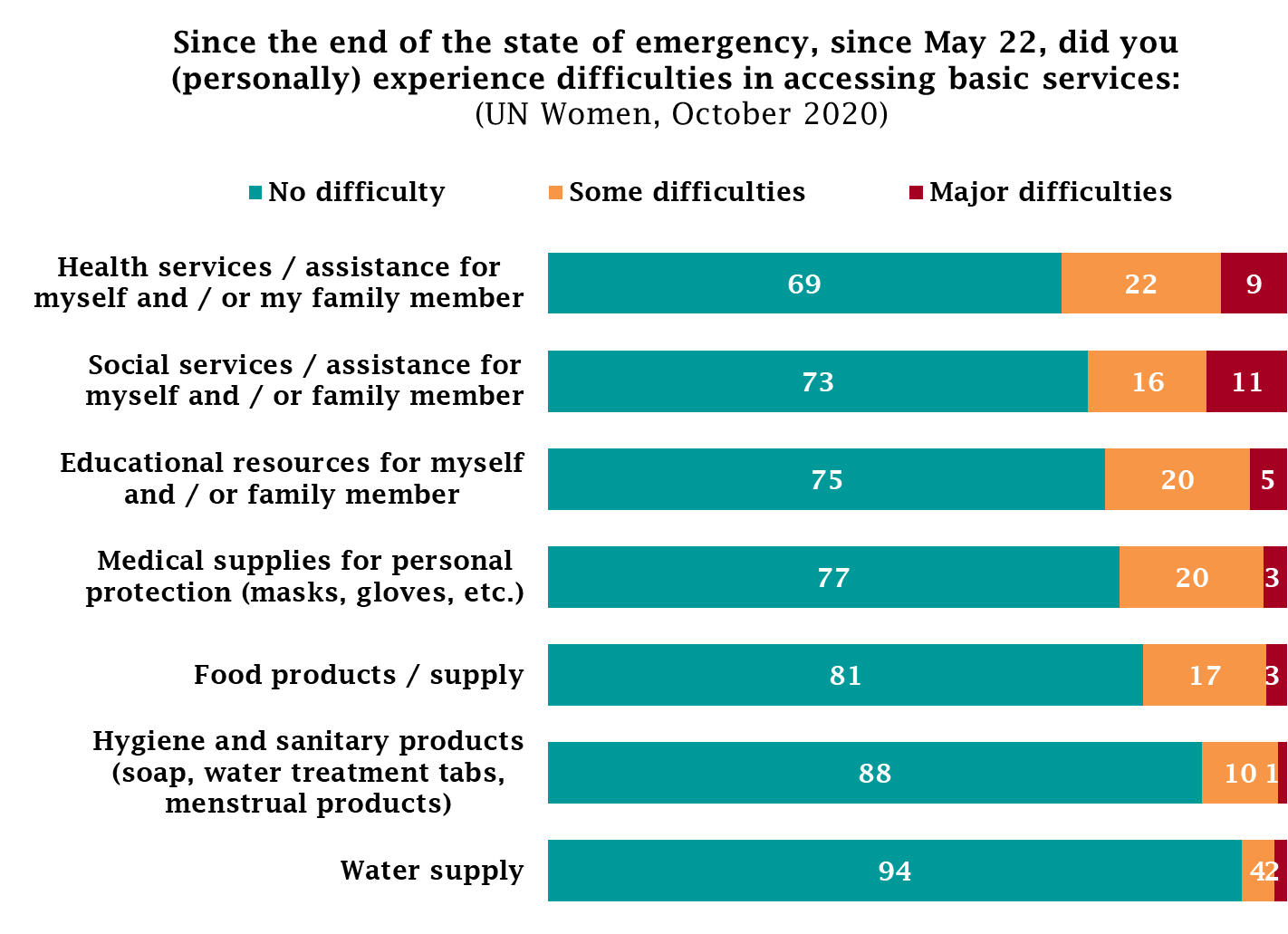

Although the majority of the population did not experience major issues in accessing basic services, around a third (31%) of Georgians reported some or major difficulties in accessing health services. Overall, 40% reported having at least some difficulty in accessing one of the services listed on the chart below. Aside from accessing services, 25% of working people also experienced a significant change in that they started working from home.

Plausibly, experiencing difficulty in accessing the important services listed above or significant changes in daily life would increase someone’s stress and anxiety levels. To explore whether this took place, a series of regression models testing for associations between these issues in addition to demographic factors are explored below.

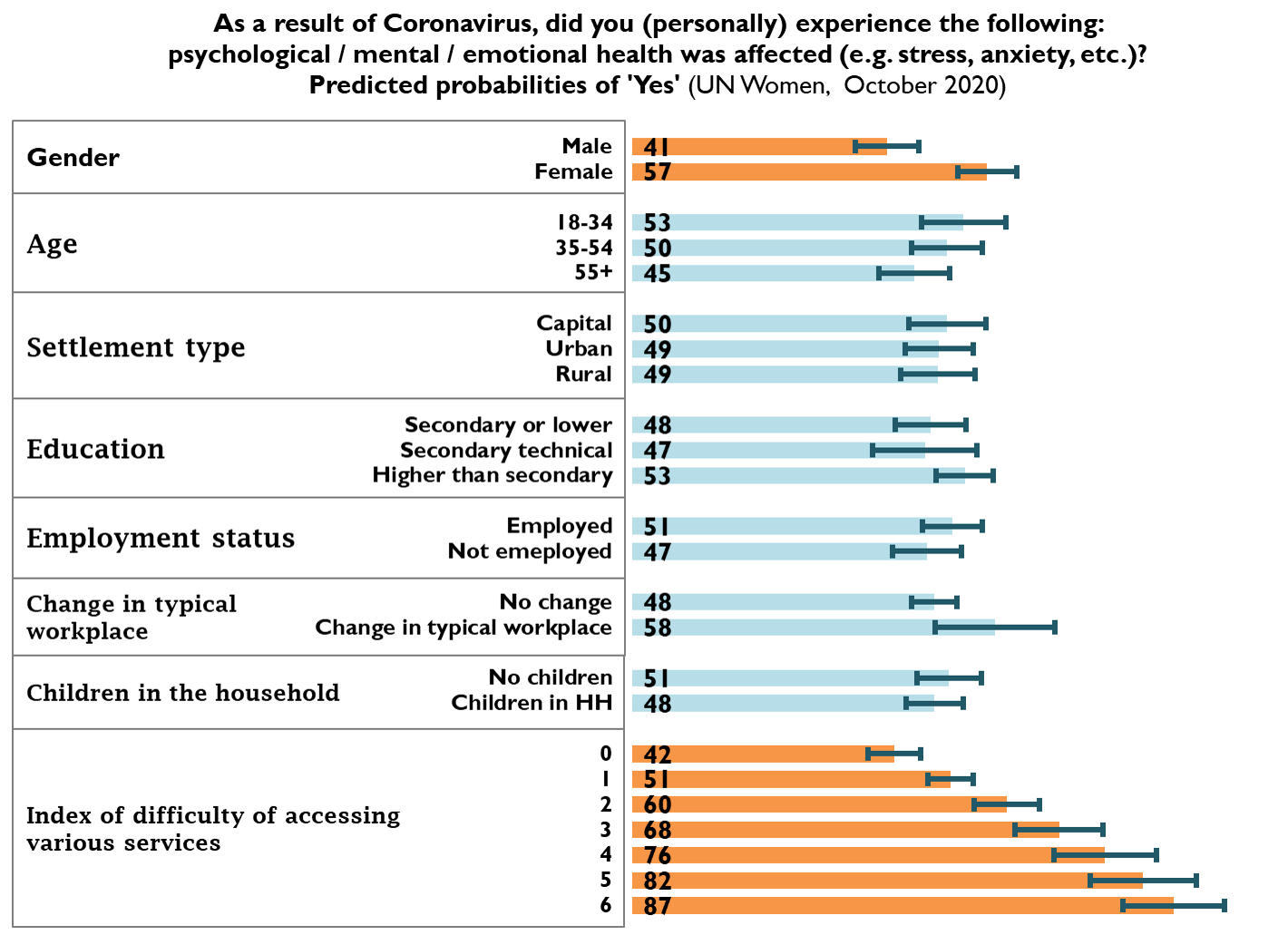

The first regression analysis shows that women were 1.4 times more likely to report experiencing mental health issues than men. There were no significant differences between age groups, settlement types, education levels, employment statuses, or whether or not the household had children living in it.

Challenges with access to basic services are associated with mental health problems, but not the move to remote work. The more difficulty a person encountered in accessing basic services, the more likely they were to report that their mental health was affected. While a person with no difficulty accessing services had a 42 percent chance of experiencing mental health problems, a person who had difficulty accessing six services had an 87 percent chance of experiencing them.

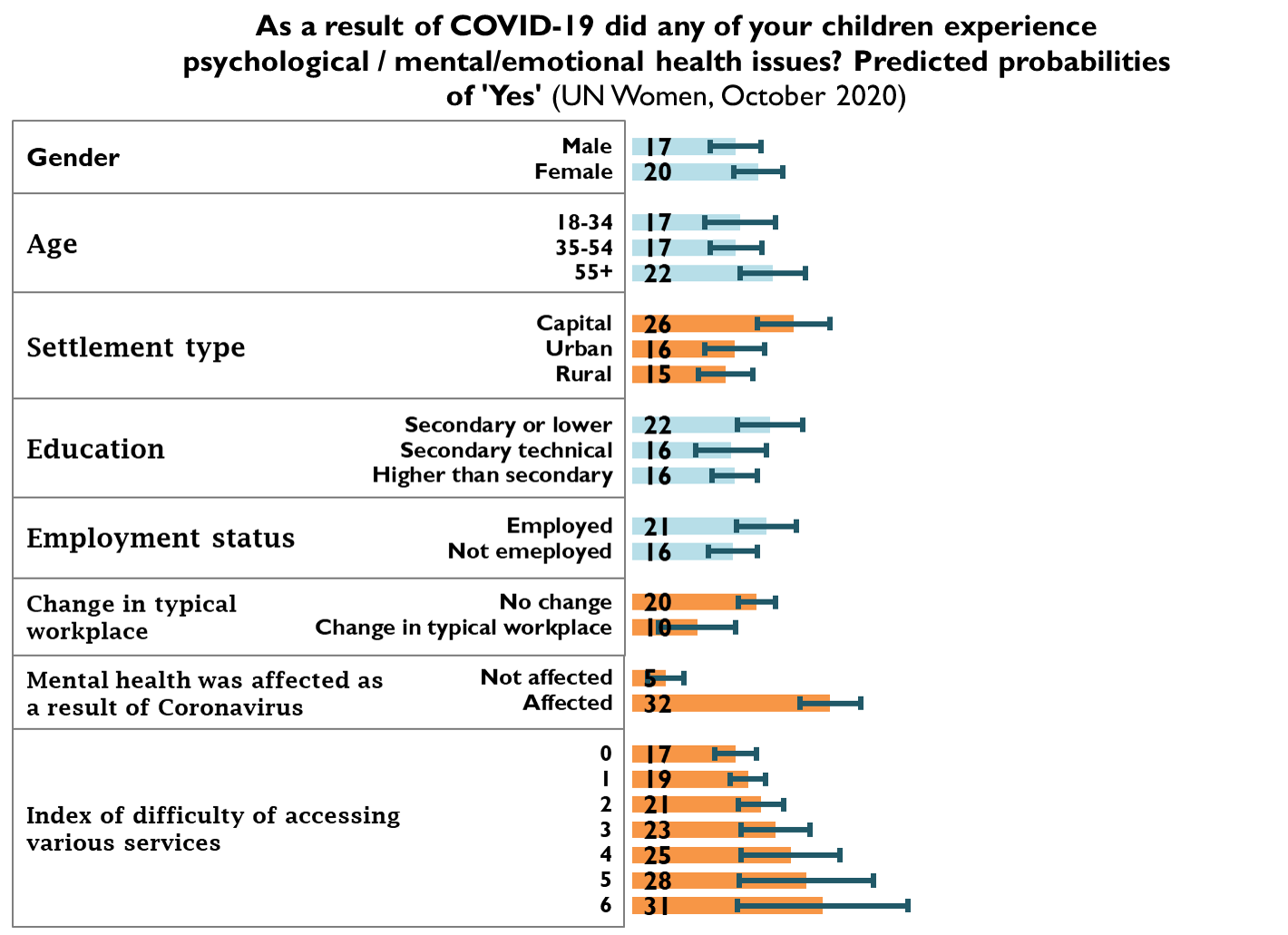

A second regression analysis also shows a number of differences between those who reported their children experiencing mental health challenges during the pandemic.

People living in the capital were 1.5 times more likely to say their children experienced issues with mental health compared with people in other urban and rural areas. There were no significant differences between genders, age groups, education levels, and employment statuses when controlling for other factors. Notably, there were gender-related differences when the regression only considered demographic factors, but the association was no longer significant after taking into account non-demographic variables.

People who experienced a change in their typical workplace were 1.9 times less likely to say their children experienced mental health issues than people who did not have any significant changes in the workplace. The more difficulty a person encountered in accessing basic services, the more likely they were to report their children’s mental health was affected. Additionally, people who reported that their own mental health was affected by COVID-19 were around six times more likely to say their children’s mental health was affected, compared to people, who did not say their own mental health was affected.

About half of the public experienced mental health problems as a result of the pandemic, and women were particularly likely to admit they experienced issues around this. Above and beyond all other factors though, people who had trouble accessing basic services were most likely to be affected.

The views presented within this article are the authors’ alone, and do not reflect the views of UN Women, CRRC Georgia, or any related entity.

The data used in this article is available here.