Human rights in the military is an issue of concern to rights groups around the world. In Armenia, reports by local and international organisations and the US Department of State suggest a concerning situation in the the country’s armed forces.

Reports of physical abuse and suicides in the Armenian army are not new. Such incidents are in part connected to a tradition of hazing, known as dedovshchina, which was practiced in the Soviet Army before Armenia regained independence in 1991. Reports indicate that abuses occur throughout the army, and range from bullying, hazing, corruption, as well as impunity for the perpetrators. Armenia has two years of mandatory military service for men aged 18–27.

The Safe Soldiers database from Armenian activist group Peace Dialogue records fatalities in the Armenian armed forces. Records are obtained from private individuals, partnering organisations, along with information gathered from the media.

The database currently includes records of more than 900 fatalities since the cessation of hostilities over Nagorno-Karabakh in 1994.

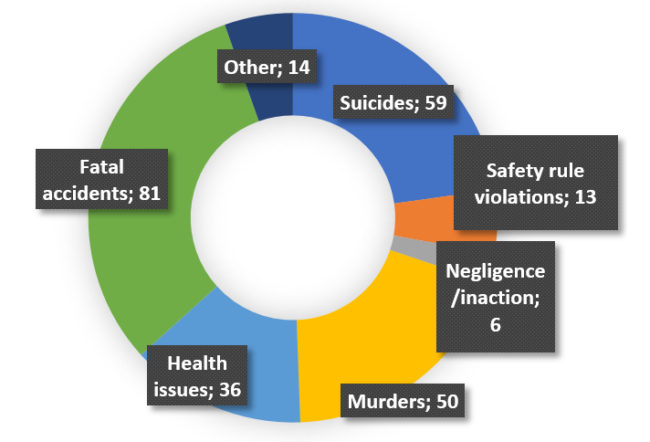

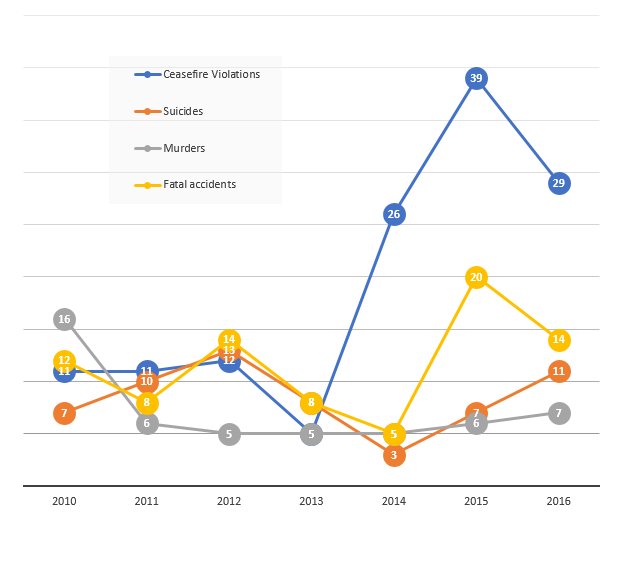

According to the database, in 2010–2016, the Armenian armed forces (including the Nagorno-Karabakh Defence Army) suffered a total of 472 fatalities. This number includes 133 fatalities during frequent ceasefire violations and 80 during the April 2016 Four-Day War, the bloodiest clashes on the Armenian–Azerbaijani line of contact since 1994.

Other causes of death recorded by the Safe Soldiers database include: suicide, murder, health issues, violations of safety rules, undefined, and negligence.

An increase in the number of murders and suicides over the last three years is a matter of concern for civil society groups in Armenia. The majority of the suicides and murders are recorded in the military units situated on the line of contact or regions bordering with Azerbaijan.

Even if the increase in the number of victims of ceasefire violations can be explained by tension on the Armenian–Azerbaijani border, the increase in the number of fatal accidents cannot. In 2015 there was an unprecedented rise in the number of fatal incidents. Accidents in civil and military vehicles are the biggest cause of death. In many cases, these were in personal cars, not vehicles that were attached to a military unit. However, under this category there are a number of incidents that are difficult to classify: drowning, falls from a height, avalanches, etc. Some of the fatalities occurred during military training. Due to a lack of sufficient information about these deaths, it is difficult to say whether the actions or negligence of co-servicemen and officers played any role.

The statistics do not entirely reflect reality, as many of the recorded cases are under criminal investigation; after these investigations are complete there could be slight changes in the figures. However, Peace Dialogue has recorded several cases where official investigators have come to the wrong conclusion.

The Armenian government has taken steps to improve human rights in the Armed Forces. In the National Strategy on Human Rights Protection adopted by the government on 27 February 2014, it was decided to strengthen measures to eliminate abuses in the armed forces, as well as to ensure a prompt, impartial, and thorough investigation of non-combat deaths. The same priority will remain in the National Human Rights Action Plan for 2017–2019, which will be adopted before April. However, many human rights activists question whether such measures are enough. In most non-combat army deaths, Armenian human rights watchdogs claim that those responsible are not prosecuted and cases are covered up, which encourages new crimes.

In 2015, Armenia’s Defence Minister issued an executive order classifying information about non-combat fatalities in the military, including information from investigations into infringements in the armed forces. Subsequently, the Armenian Defence Ministry has refused requests by Peace Dialogue for information including the names, unit numbers, and commanding officers of deceased soldiers, as well as details of fatal incidents like the locations, dates, and causes of death. According to the organisation, the order severely limits the ability of civil society to maintain civilian control over the Armenian military, and to ensure their compliance with their human rights obligations.

Despite this, the Armenian military enjoys one of the highest levels of public trust of any institution in the country, especially among young Armenians. According to the ‘Between Freedom and Security’ study by Peace Dialogue, the armed forces is the only institution with a significant discrepancy between trust and transparency. To this point, 65% of respondents trust the army, while 62% believe that they are non-transparent.

Respect towards human rights ranked last on the list of young people’s priorities in regards to strengthening the Armenian Army. The army has such widespread respect in the country as it provides the only security guarantee against the backdrop of Armenia’s unresolved conflict with Azerbaijan. As a result, three quarters of young people believe that problems and incidents in the army should not even be discussed or publicised.

The author hopes this analysis will encourage our colleagues from other countries in the South and North Caucasus to study the issue in the military forces of their respective countries.