In 2018, Armenians peacefully ousted their government in a fast-moving decentralised revolution. Six years on, and amidst regional upheaval, participants of the Velvet Revolution assess the key factors in the movement’s success.

In the run-up to the spring of 2018, a change of government in Armenia seemed unlikely at best.

Opposition to Serzh Sargsyan’s government had been steadily growing, intensifying in light of the announcement on 12 April that he would run for prime minister, having served two terms as president.

Four years earlier, Sargsyan had vowed that he would not ‘display any claim on the position of Prime Minister’. A constitutional referendum held by his party two years after he won the presidency in 2013, however, appeared aimed at ensuring precisely that: by shifting Armenia from a semi-presidential to a parliamentary system, Sargsyan would be able to bypass the two-term limit for serving as the country’s president, and continue leading the country.

His backtrack sparked outrage, and ignited the fuse of the protests that would end up ousting him, with ‘the people’s candidate’ Nikol Pashinyan elected prime minister by parliament on 8 May, less than two months after Sargsyan’s bid for the position.

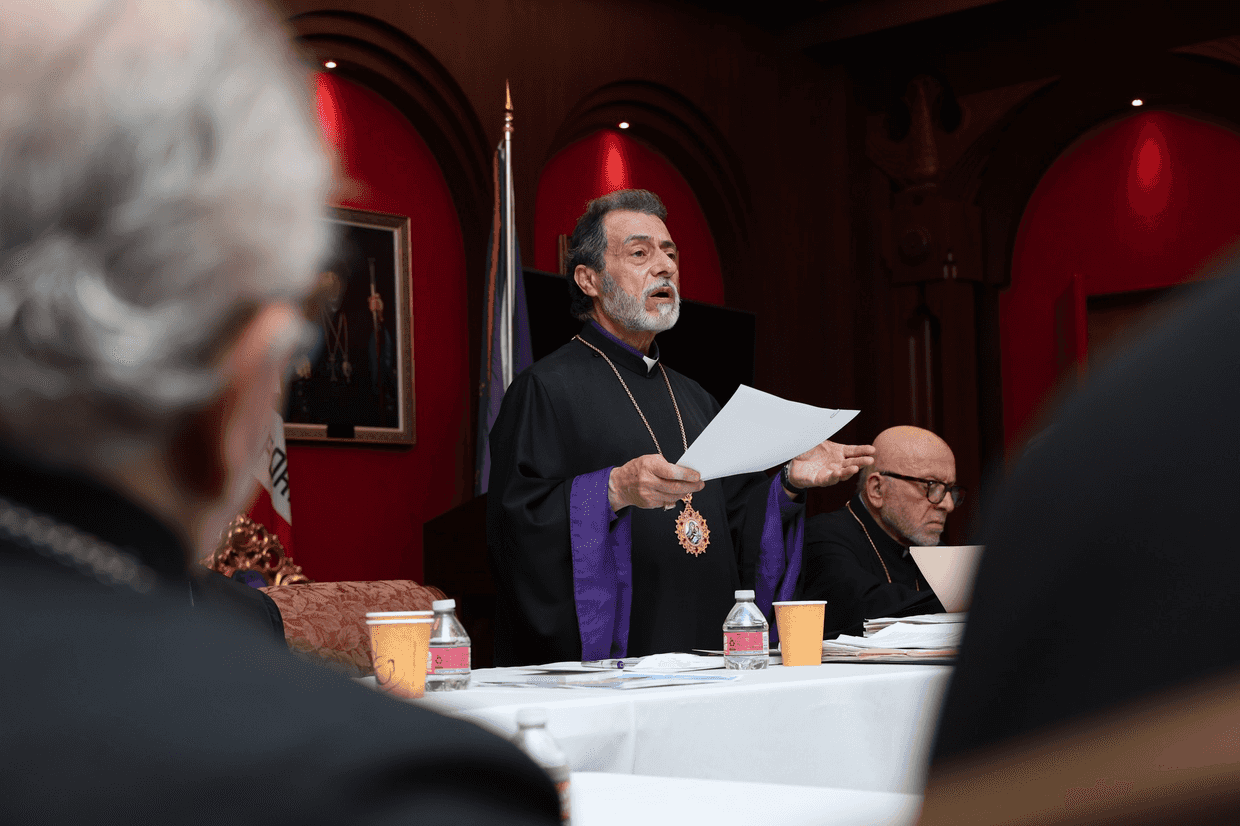

Speaking to OC Media, leaders and participants of the movement attributed its unprecedented success to the use of innovative and unprecedented tactics that brought together not just political parties and civil society, but tens of thousands of people across the country, in a movement that put ordinary citizens in power.

Rejecting Serzh and the system

At the time of the revolution, Sona Ghazaryan was working in media and public relations for a civil society organisation.

Her favourite photograph from those days hangs above her head in her office in parliament, where she now serves as an MP with the ruling Civil Contract party. ‘Malishka [the name of a village] is with Pashinyan’, reads the poster a protester holds in the photo, taken by her husband.

Ghazaryan was one of the founding members of the Reject Serzh movement, which formed in response to Sargsyan’s entrenching his hold on power.

‘Of course, Reject Serzh was not about the person, it was more about the system, but the best example of it was Serzh Sargsyan’, explains Ghazaryan. After the group’s founding at the beginning of March 2018, they held meetings every evening to plan and prepare their next moves.

‘We didn’t have high expectations, but we said that we should at least try, because unlike some undemocratic states, where civil society and the youth seemed to no longer want to take any initiative, we [could] still try,’ says Ghazaryan.

Following their founding, the group had two primary objectives. The first was raising awareness of the issues that they were protesting, because they believed that young people felt both indifferent and frustrated. The second was to expand their membership, for which they invited prominent young people from other initiatives and NGOs to their meetings.

Davit Petrosyan, then a student, was one of those to join, and was tasked with getting more students involved.

Petrosyan says that one of the movement’s main goals was to combat a sense of hopelessness, as many people had believed that the government would not leave its seat in power, and would use force to ensure that that was the case.

To change what people thought was possible, the movement used humour in their actions challenging the regime, at one point launching a fundraiser with the stated aim of helping Sargsyan retire.

‘The important thing was to attract attention and make it a bit cool, lighter. That way, it was perceived as a political process, but rather than being perceived as a struggle of parties or individuals for power, it was about ideas,’ says Petrosyan.

Although the movement’s initial events did not attract large numbers, their energy, optics, and humour meant they had a much wider impact.

Uniting efforts: ‘Take a step, reject Serzh’

As Reject Serzh sought to engage people and challenge their assumptions, opposition leader Nikol Pashinyan and his party, Civil Contract, developed their own approach to fighting against Serzh Sargsyan’s tightening grasp on power.

On 31 March, Pashinyan announced that they would that day begin a march from Gyumri, Armenia’s second-largest city, to the capital. The ‘My Step’ march was based on Mahatma Gandhi’s ‘Salt March’ and theory of nonviolent disobedience.

Before the march began, the party invited members of civil society and the opposition to attend its presentation and join the action.

Petrosyan, who was present at the meeting, says that no agreement was officially reached between the various anti-government actors, but that there was in effect a ‘silent agreement, because everyone started to do their work’.

At the end of March, My Step began its walk to Yerevan, as the Reject Serzh movement continued its actions within the city. Members of each movement attended the other’s events: a manifestation of that ‘silent agreement’.

Speaking to OC Media, participants of the Reject Serzh movement gave a few reasons for why they chose not to unite at that point, highlighting previous disagreements with Pashinyan’s team on other issues, and an unwillingness to associate with the party.

‘I had questions myself, because there was a lot of mistrust towards parties, not from me, but from society’, says MP Ghazaryan. ‘I was very afraid that cooperation between civil society and the party might look bad in the eyes of the public.’

She adds that the question of whether or not to join forces was not ‘acutely’ addressed. Instead, thoughts and doubts arose, and then dissipated as time went on.

Pashinyan and fellow marchers arrived in Yerevan on 13 April. They were welcomed by members of the Reject Serzh initiative, Pashinyan’s supporters, and others. On the same day, the two movements held a joint rally in front of the Yerevan Opera House on Liberty Square.

The names of the two movements were later brought together into one of the main slogans of the movement: ‘Take a step, reject Serzh’.

Blocking streets and calling on police

‘[Go] to the rally like to work’ was a refrain amongst the protesters. Ghazaryan recalls the energy of the time, noting how inspiring it was that every day, new people, organisations, and entire workforces of factories joined.

At the end of every day of protesting, a rally would be held in Republic Square, at which Pashinyan would set the next day’s task: a strike, blockading administrative buildings, blocking roads, and more.

The protests were characterised by a deliberate openness and non-violence. Anyone who wished to join was welcomed with an ‘open arms’ policy, while police were considered not representatives of the government, but brothers who were called to join the movement.

Davit Petrosyan says that during the protests, people often gathered in the Civil Contract office to discuss and analyse their actions and next steps.

‘The principle was very democratic, people would come and join. Ideas were proposed.’

According to Petrosyan, Pashinyan’s daily announcements communicated the decisions made in that office, but many others were made spontaneously.

One key move agreed outside of the Civil Contract offices was the decision to decentralise the movement, which ended up being critical to the revolution’s success.

Ghazaryan believes that the idea arose in several places and became a consensus. Petrosyan, on the other hand, remembers the decision being made on the morning of 15 April, in Saryan park in downtown Yerevan.

According to him, members of the movement were discussing what to do in light of a decline in the number of people protesting. He recalls Suren Sahakyan and Armen Grigoryan, members of the Reject Serzh movement, suggesting the change of tactic.

They proposed that instead of waiting for people to gather and eventually going to the parliament building, decentralising the protests would both empower individuals to take action on their own, and make it harder for the police to contain protesters.

Vardine Grigoryan, from the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly — Vanadzor, a local human rights group, states that while collective responsibility usually became ‘individual irresponsibility’, on this occasion it was unexpectedly effective.

‘Here, in a way, everyone was responsible for their own area, deciding independently what their remit was, and what they did. That self-organisation seems to me to have been very successful’, says Grigoryan.

Petrosyan recalls agreeing in the same discussion that the movement would mobilise students to block a central street, beginning early in the morning, and collecting public bins to form a barricade.

The objective was to close the intersection in front of the Medical University in central Yerevan the following morning. Shutting down the roads near the main universities would disrupt traffic, stop students from reaching their universities, and potentially encourage them to join the protests.

While Petrosyan joined the movement as an individual, he notes that the student-led Restart initiative played a significant role in the revolution’s success, with others similarly noting that the revolution would not have taken place without students’ active involvement.

Restart was initially focused on a law restricting male students’ right to defer military conscription based on their studies, with their focus later shifting towards advocating for university reform. However, the group soon recognised that addressing even relatively minor issues would require approval from the political elite, and changing the system could take years.

According to Petrosyan, it was this that led the group to join the broader movement calling for Sargsyan’s resignation.

For MP Ghazaryan, the moment that students joined the protesters in the city centre on 16 April was a turning point. The decision to join the movement not only put the students’ frustration into action, but also defied pressure from universities to prevent students from participating.

The other breakthrough moment she recalls was on 22 April, when the movement’s leaders were detained but it continued regardless.

‘That meant there were no tools left to fight against it’, says Ghazaryan.

What contributed to the movement’s success?

Grigoryan notes that civil society organisations came together to support protesters, with a number of organisations offering protesters free legal support to help them challenge their charges and fines.

She also notes that the presence of civil society organisation members during protests in Vanadzor ‘restrained the police’s behaviour’.

However, the role that individual organisations played in the movement varied. The Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly — Vanadzor attempted to minimise their visibility, in light of public pressure against their participation, linked in part to their receiving grants from the Open Society Foundation, as well as accusations that they sought to harm Armenian-Russian relations.

‘It was very unpleasant. We were very careful and attentive in this regard, so that any association with us in this case did not have a negative effect in any way and people felt ownership [of the movement],’ says Grigoryan.

She adds that drone footage was an unexpectedly significant factor in the movement’s success, as it allowed people to understand the scale of the protests, and prevented the government or media from diminishing them.

MP Sona Ghazaryan gives a few reasons for the movement’s success, noting firstly the ‘accumulated energy’ from long-running frustrations with the government, stating that an ‘explosion’ was inevitable.

She adds that conversations between citizens and the movement’s leaders at protests were notably sincere, and a contrast with previous rallies, which had felt ‘more like a lecture’.

She also notes that young people were a ‘very strong driving force’, with the movement’s creativity and decentralised nature — where every individual became a leader — also contributing to its momentum.

‘People felt very seriously valued, and that is the most important revolution that took place in people’s minds,’ says Ghazaryan.

Petrosyan similarly notes the build-up of resentment against the previous government, and adds that the movement’s being led by people ‘with a clean past’ was critical to attracting wider participation.

In total, the movement took around a month and a half from the beginning of the My Step march to reach its conclusion.

On 17 April the National Assembly elected Serzh Sargsyan as Prime Minister. The same evening, Pashinyan announced the start of the non-violent Velvet Revolution.

He noted that every protester was a leader of the movement, which meant that the revolution could not be stopped ‘by neutralising one person’.

Sargsyan resigned less than a week later on 23 April, a day after Pashinyan’s detention and release.

‘The movement in the streets is against my tenure. I am fulfilling your demand. I wish our country peace, harmony and common sense’, wrote Sargsyan.

After Parliament voted down Pashinyan’s nomination for prime minister on 1 May, tens of thousands brought Armenia to a standstill, with roadblocks paralysing Yerevan and the country’s major highways.

On 8 May, Pashinyan was elected as prime minister. Speaking on Republic Square the same day, Pashinyan told Armenia’s citizens that ‘today you won’.

‘But I want to clearly state what your victory is. The victory is not that I have been elected Prime Minister of Armenia, the victory is that you have decided who will be the Prime Minister’, said Pashinyan.

‘It doesn’t matter who will be the Prime Minister, today and hereafter, only one subject has the right to decide who will be in charge. That subject is the citizen of the Republic of Armenia’.