The Georgian Parliament has passed amendments to Georgia’s broadcasting law that would allow a state regulatory body to fine outlets for airing hate speech. Watchdog groups warn that the changes could be used to issue debilitating fines against broadcasters critical of the government.

Members of the ruling Georgian Dream party voted overwhelmingly in favour of amendments to Georgia’s Broadcasting Law on Thursday, ignoring warnings from international and local watchdog groups.

The amendments are allegedly intended to curb ‘hate speech and incitement to terrorism’ in TV and radio programmes and advertisements.

A clause added to Georgia’s Law on Broadcasting bans media content that incites violence or intolerance based on disability, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, sex, ethnicity, race, faith, or financial status.

Exceptions will be made for any television or radio coverage of issues pertaining to these topics.

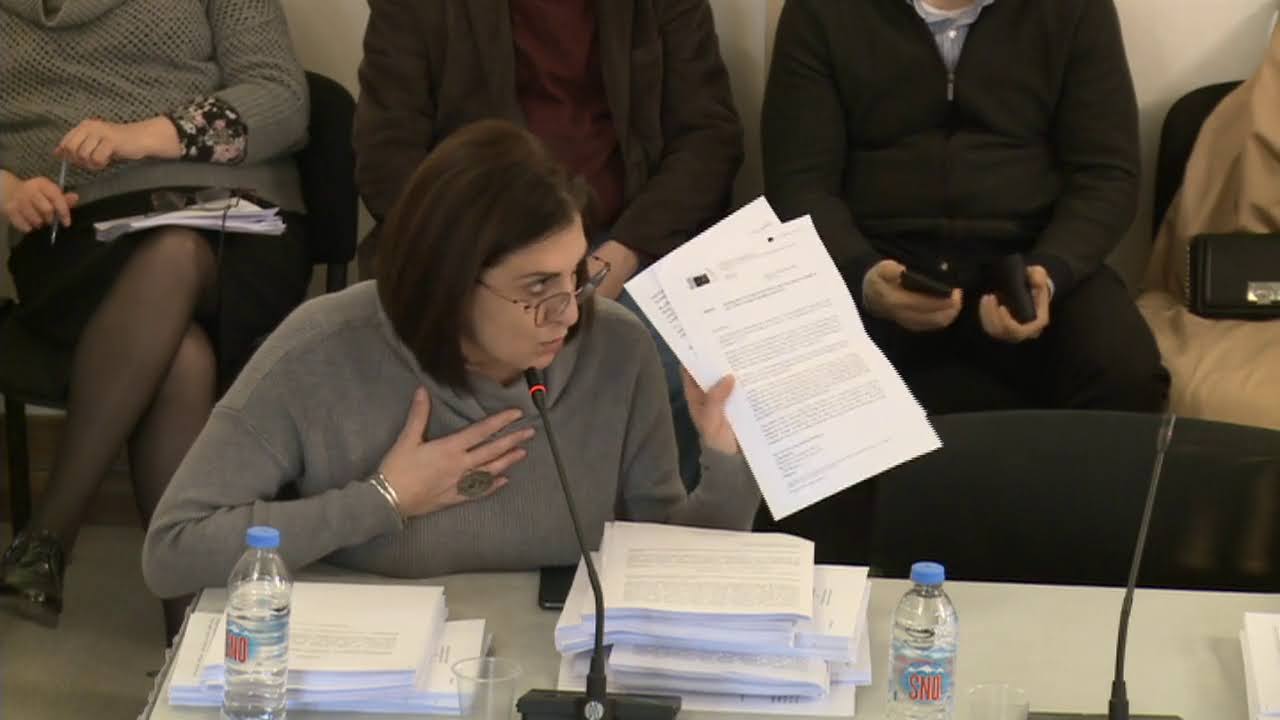

Eka Sepashvili, one of the authors of the bill, said the amendments fulfilled commitments outlined in the EU–Georgia Association Agreement, and were a ‘move in the right direction toward the enlargement of the European Union’.

However, watchdog groups warned that the changes allow the state to fine media outlets for inciting hate speech through the Georgian National Communication Commission (GNCC), the media oversight agency that the bill exclusively relegated monitoring hate speech to.

In recent years, the GNCC has been accused of targeting media groups for their criticism of the government, accusations the agency has firmly rejected.

[Read more on OC Media: Georgian Communications Commission levies fines on TV channels for ‘political’ content]

The changes to the law will also allow public officials to appeal to the GNCC for a ‘right to reply’ if they find coverage about them to be factually incorrect or one-sided. Broadcasters will be given a grace period of 10 days to address grievances submitted to them about their coverage before a GNCC investigation is launched.

A shift in power

In recent years, licensed broadcasters were obliged to have their own internal self-regulatory groups that acted alongside the Charter of Journalistic Ethics, a union and self-regulatory group that oversees ethical violations in the field. Those unhappy with the coverage of a broadcaster were encouraged to resolve disputes using internal regulatory processes, before taking issues to the Charter or to court.

Some Georgian officials, including leading Georgian Dream figure and Mayor of Tbilisi Kakha Kaladze, have recently opted to directly sue journalists in court and bypass the self-regulatory mechanisms.

The new changes to broadcasting law look set to further distance regulation of media from media organisations, and shift power towards the state.

According to Mariam Gogosashvili, the director of the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics, the amendments to the law are vague and open to interpretation.

‘There is a big possibility to misinterpret the [new] clauses and use them against broadcasters critical of the government’, she says.

Gogosashvili believes that Georgian legislature should instead create a format that would require experts and broadcasters, as well as a state regulator, to be involved in any dispute.

This was suggested by civil society groups and spearheaded by MP Tamar Kordzaia during the second hearing on the package amendments, but these suggestions never made it to the final amendments of the broadcasting law.

The Charter of Journalistic Ethics, the larger Media Advocacy Coalition, and the international media watchdog the Committee to Protect Journalists, have all been critical of the initiative that was put to the vote on 22 December.

According to Gogosashvili, ‘despite our numerous requests, there was only one working meeting in parliament, without any follow-up meeting to discuss the package law point by point’.

‘We did not even receive a reply to our written request’.

Gogosashvili informed OC Media that the authors of the package bill also received ‘initial’ feedback on their initiative from Council of Europe law and media governance experts Eve Salomon and Sally Broughton Micova.

In their letter dated 25 November, the Council of Europe experts noted that the discussion of the package tabled a month earlier had not been inclusive of civil society groups and key stakeholders including the broadcasters.

The experts also recommended that serious sanctions against broadcasters, like fines in the amount of up to 1% of a broadcaster’s annual income or suspension of a licence, should not be immediately implemented if they were challenged in court.

[Read more on OC Media: Three TV channels sanctioned at request of Georgian Dream]

Salomon and Broughton Micova cited ‘problems with the inefficiency of the Georgian judicial system’ as a factor in their suggestions.

Criticism from the right

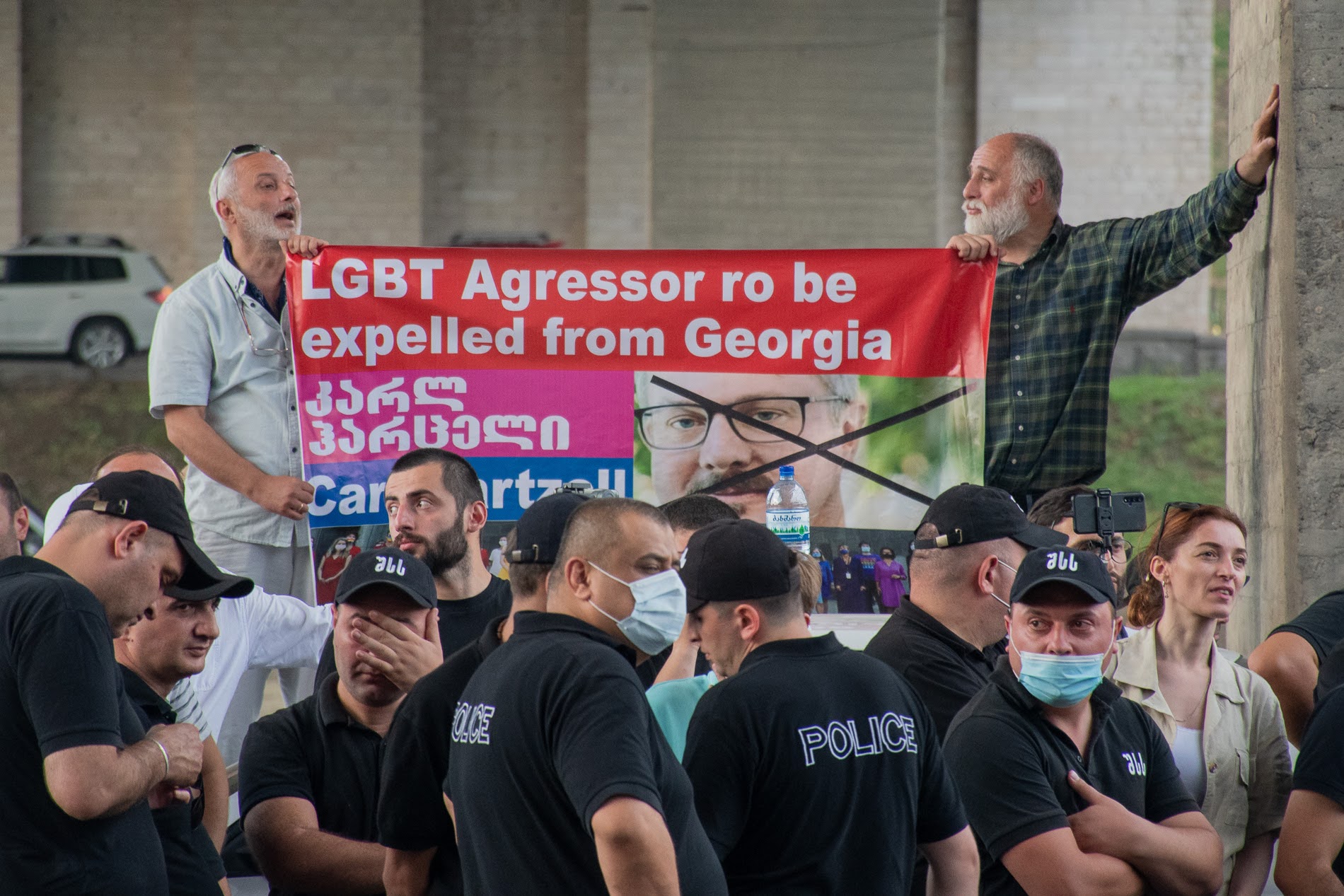

The amendments have also found enemies in Georgia’s right-wing political spectrum, ranging from centre-right to far-right actors.

Critics of the bill included members of parliament from the centre-right United National Movement party and the libertarian Girchi — New Political Centre party.

Girchi MP Herman Sabo claimed in a 19 September parliamentary hearing that the changes meant that ‘if I claim on air that I think there are only two genders, someone may treat it as hate speech and seek to fine me or a TV [channel].’

‘The freedoms that we have, those that are still intact and are not constrained by identity politics and neo-Marxist theories […] I believe we should cherish them more’, added Sabo.

Similar ideas have been put forward by ultra-conservative political figures, including members of the extremist political party Conservative Movement and far-right campaigner Guram Palavandishvili, who attended the parliamentary hearings.

‘After adopting this bill, if one reads out specific passages from the Bible on air, a TV channel would be stripped of its licence’, Conservative Movement’s Zurab Makharadze warned in September.

Giorgi Chelidze, a Georgian neo-Nazi leader, also released a fiery video address criticising the bill in September, in which he accused ‘Western liberals’ of pressuring Georgian Dream to silence those Georgians who were against ‘perverted sexual relations and multiculturalism’.