On 10 March, Gyumri, the second-largest city in Armenia, was listed by Forbes among the 17 best spring destinations for 2020. Local residents were delighted by the news, and tourism operators and entrepreneurs began to prepare for a large influx of tourists.

However, a few days later, that expectation was replaced by uncertainty.

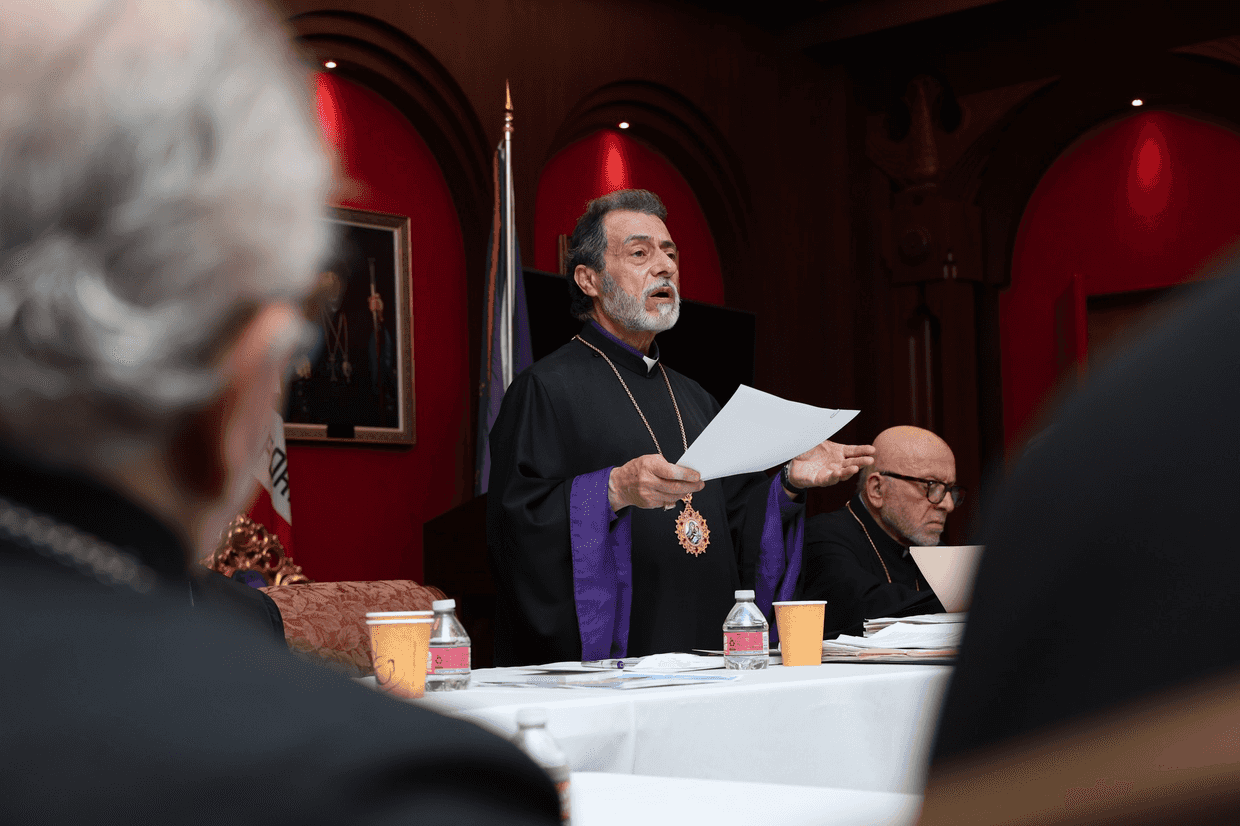

The first case of coronavirus infection was already confirmed in Armenia on 1 March. The number of people infected quickly increased, as the infection spread across three branches: from those who arrived from Iran, and also from a resident of Echmiadzin, who became infected with the coronavirus in Italy and arranged an engagement upon return, and from a factory in Yerevan.

To prevent the spread of coronavirus, a state of emergency was introduced in Armenia on 16 March. Under it, mass events are prohibited; hotels, restaurants, and cafes that survived the difficult winter season have closed indefinitely.

The state of emergency continues to dictate new conditions every day. However, the demands of the government and their perception by people, have not always matched.

In the first two days after the declaration of the state of emergency, a rush on the stores to buy essential goods began.

Some entrepreneurs took advantage of the situation to raise food prices. But in the following days, state inspection bodies began to monitor prices, and the government provided data on an adequate supply of products in the country. Now people make regular purchases on demand.

However, up until the announcement of a more strict regime, the city had two different daily lives. Some did not leave their homes — isolated people were looking out of the windows or from the balconies. They were convinced that by staying at home, they could save not only themselves but also others.

Others ignored the infection, went outside, worked, chatted, then played backgammon and made excuses.

‘The virus is dangerous in an enclosed space and next to strangers, and we are in the open air and know each other. None of us is sick’, one man said.

Such a cavalier attitude was observed not only in Gyumri, but also in the capital, where some cafes and restaurants even began to work.

On 24 March, the Armenian government announced a new, more strict regime. Now people can leave their homes only when necessary, for a short time and with an identity document, while the elderly should only shop at certain hours.

After 24 March everything was closed, the streets became empty, and the police began to fine disobedient people. In public transport, all drivers began to regularly wear masks, gloves, and to disinfect coins. Passenger flow was also significantly reduced.

In addition to drivers, only grocery store employees, bakers, bank attendants, medical staff, and some cleaners, continue to work outside of the home. Under strict conditions, those restaurants and cafes that worked part-time were closed, and food delivery also stopped.

The owner of one cafe in Gyumri, Artush Yeghiazaryan, was among the first to close his doors, realising that people’s health was more important. He says he was surprised that the neighbouring establishments continued to work.

Yeghiazaryan told OC Media that after the declaration of the state of emergency, the requirements were unclear:

‘The government did not specify about bars at the first emergency meeting. They did not prohibit the operation of restaurants, but also prohibited the gathering of more than 20 people. But a week later, when the conditions were clear, all service facilities closed their doors’.

According to Yeghiazaryan, development prospects were outlined by the government in Shirak Province. But despite this, according to official statistics, the region leads in the number of unemployed.

‘We got out of the difficult winter season and we were very happy to enter this [new] season, which was very promising. Thanks to the tremendous efforts of the president, government, and certain individuals, Gyumri has a new opportunity to stand up and develop’.

Despite the crisis, Yeghiazaryan is optimistic.

‘It’s really hard, but at the same time there are areas that work and make a profit, such as grocery stores and mask makers. I think that after this global freeze we have many positive, happy years ahead. And during this time we all must learn to build a new reality, to be a society that will be financially and spiritually fair.’