On 16 March, the bodies of 12 people who died during the 1992–1993 conflict in Abkhazia were returned to their families. Lika Managadze, whose father Akaki was among the dead, reflects on her memories of her father and how the war shaped the course of her life.

‘I was born in Abkhazia, in the village of Aradu in the Ochamchire region. I was only five when the war broke out; my brother was seven and my mother 30. We were in a corn-field when planes flew over us and opened fire.’

‘My brother was very scared. He put his hands over his head. I remember telling him not to be afraid and that everything was going to be alright. But very soon we had to leave.’

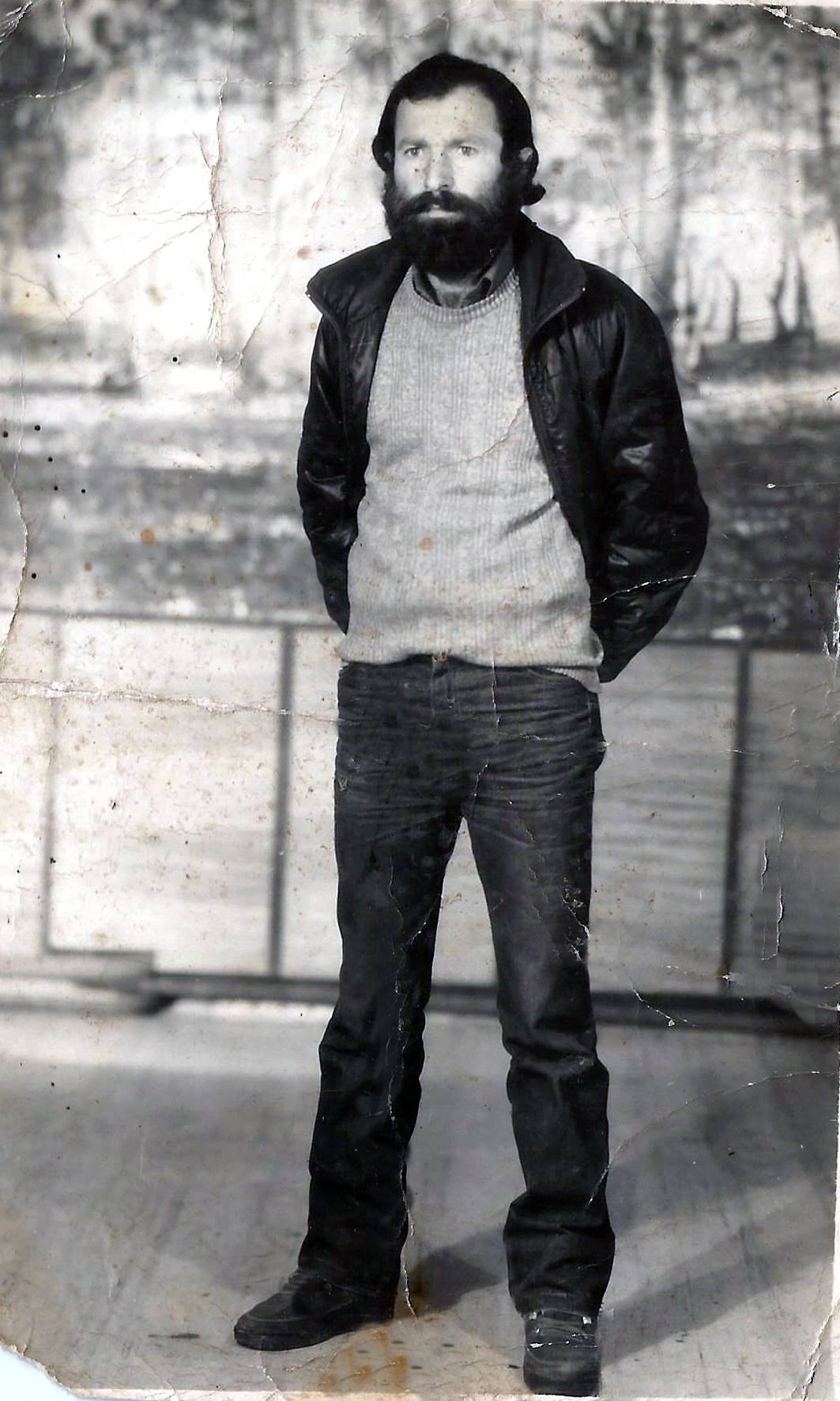

‘I remember what my father was wearing the last days we were in Aradu. He was wearing his blue jacket. I saw this jacket three days ago in the photos in my father’s case file. I recognised it and it made me really happy. It was like my father was alive again.’

‘Before we left, my father told my mother to take me and my brother and leave and that he had to stay because he had brothers there and he wouldn’t leave them.’

‘We left together with many other people. We took that rusty old electric train. What I remember from that train-ride was that it was full of people and there was a smell of corvalol drops.’

‘We arrived in the small village of Kheta, where my mother had relatives. One of our relatives sheltered us for several months. I remember her being sad and crying at night, holding a list of the missing and dead from war. Then we moved to an abandoned private house in the same village and a few other families also moved there with us. Kheta is the village where we buried our father on Sunday.’

‘I remember I thought the actor John Travolta looked like my father and each time I saw him on the TV I would call my mother, telling her that he was alive. She would hug me then.’

‘I have few fragments in my memory from my childhood before the war. I have few memories of my father. I remember his face, his different jawline, which I later recognised among the photos of his skeleton. My father was a football player. He was very quick and was always praised for his rapid and smart movements during matches.’

‘I also have a memory of him drinking ice-cold well water from an enamel teapot with cherries and flowers on it. He used to pick white cherries in the garden and would put them on my ears saying that they were earrings. He used to put me to sleep in the hammock and sing a song, which I still remember.’

‘The warmest memories of my childhood’

‘When we lived in Kheta, my mother began to pick violets; I would help her. We would make them into small bouquets that we would then sell. We sold a huge bag full of violets on 8 March. This way, she collected money to buy a goat.’

‘I used to take care of this goat, whom we named Pudzhia. This is one of the warmest memories of my childhood. My mother got a job as a seller in a tiny red booth in the centre of the village. I took care of my goat, my brother would play football, and we both went to school. We managed everything somehow.’

‘My brother and I really loved living in a village. But the problem was that the school was five kilometres away from our house and we had to walk through five kilometres of hills every day to get to school. It was difficult. My mother’s booth was right in front of the school and she was there from 7 am to 6:30 in the evening.’

‘When I turned eight, mother took us to Novoshakhtinsk in Russia to be with her brothers. My brother and I had to skip one year at school. Mother was selling fruits and vegetables there and was saving some money. Seven months later, we returned to Georgia.’

‘With the help of her brothers, my mum purchased a small flat in Poti (I think it was $800), and she chose a place right in front of the school. We stayed there for all these 17 years and never moved anywhere after that until this day’.

‘My mother always supported me’

‘I have been singing since childhood. I preferred to sing folk songs. In the early school years, we couldn’t afford my music lessons, so I didn’t practice. But when we got back to Poti, I joined the school’s music studio and started practising. When my class graduated, I was the only one to sing and I remember singing Celine Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic, which was really popular back then. I felt amazing, positive vibes from the audience that day and knew that this was something I wanted to do my whole life.’

‘My mother always supported me and she did her best to help me build my career as a musician.’

‘When I was in my first year of university, I got married and had a child. I decided to take a break for three years and just last year, I moved to Tbilisi to continue my education at the Tbilisi State Conservatoire. My mother and my brother, with his family, still live in Poti.’

‘We were always waiting for him’

‘We still believed that he was alive and that he would come back. We were always waiting for him. He was on this list of missing and dead people, but we still thought that we would find him and one day he would return with a long beard. This is how I imagined him. He loved having a long beard.’

‘The Red Cross came to us in 2013. They took a DNA sample from me. I was pessimistic. I did not believe it was possible; years passed. Last year, my brother told me that our father’s body had allegedly been identified and had been sent abroad for an expert opinion. On 7 March this year, he called me again and told me that father’s body had been found.’

‘I was in shock. I was crying and was happy at the same time. It had a negative effect on my mother. She was feeling bad for these five years [since the Red Cross contacted them], I guess because deep inside she still believed he would return. My mother never remarried. She said she couldn’t betray father. She saw him as a hero and kept saying that she would never do that to him.’

‘In the end, this war had a negative influence on my childhood, but it didn’t twist me into a bitter person. Life continues and I am very optimistic. I am a patriotic person. I love my country, I love Abkhazia and Abkhazian people, and if I had a chance, I would definitely visit my village Aradu and our house there.’

Thousands unaccounted for

Akaki Managadze, born in 1955, and his brother Givi Managadze, born in 1938, both fought in the 243rd Battalion of the 24th Brigade of the Georgian Armed Forces. Both died in September 1993 during an attack on Aradu, a village in the Ochamchire region in Abkhazia.

Their bodies were found in the village and were handed over to their families last week.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, 23 people were identified in 2019. Fifteen of those — 12 ethnic Georgians and three Abkhazians — went missing during the 1992–1993 conflict in Abkhazia. Eight went missing during the 2008 August war, among whom seven were Georgians and one was Ossetian.

The 12 Georgians who went missing during the conflict in Abkhazia were handed to their families on 16 March; the rest will be handed to their families on 26 March. According to Georgia’s Ministry of Reconciliation, seven of those returned were members of the military, one was a volunteer, and four were civilians.

In 2010, the Red Cross set up a mechanism to collect information about missing people from the conflicts in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. The only goal of this mechanism is to discover the fate and location of those still missing.

According to the Red Cross, around 2,300 people, including both soldiers and civilians, remain unaccounted for. Since 2013, the remains of up to 500 people have been recovered, of which around 200 have been identified and handed over to their families.

[Read a voice from Abkhazia: ‘The war robbed me of everything’]