While the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh rages on, mixed Armenian–Azerbaijani families in Georgia continue to thrive. Such families face many difficulties — not least their inability to travel to each others’ countries — and wish for more peaceful times to return.

While the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh rages on, mixed Armenian–Azerbaijani families in Georgia continue to thrive. Such families face many difficulties — not least their inability to travel to each others’ countries — and wish for more peaceful times to return.

[Read in Armenian — Հոդվածը հայերեն կարդացեք]

There are no figures on the number of Armenian–Azerbaijani couples in Georgia, but anecdotally, such families are not hard to find. Some were formed before, and some even after the conflict heated up in the 1990s.

‘What’s the difference…?’

Twenty-seven-year-old Georgian–Armenian Zemfira Kirakosyan, who’s named after her Azerbaijani grandmother, married Ali ten years ago. Ali’s mother is Armenian and his father is Azerbaijani.

Though her grandmother was an Azerbaijani, Zemfira grew up in an Armenian environment. She considered herself first and foremost to be Armenian, attending an Armenian Apostolic Church in Tbilisi.

‘When I first met my husband, there was no question for me that I was Armenian and that he was Azerbaijani’, Zemfira tells OC Media. She continues to attend Divine Liturgy on Sundays at the Armenian church, celebrates Armenian holidays like before, and even speaks Armenian with Ali.

‘What’s the difference…? The only difference is that my husband’s surname is Azerbaijani, while mine is Armenian’, explains Zemfira. The only problem she sees is her inability to travel to either Azerbaijan or Armenia with her husband.

Broken families

This is not the sole problem created by the conflict for families like Zemfira and Ali’s; it has also caused splits between many mixed families and their relatives. Azerbaijani woman Nazli, who was born in Tbilisi and married a local Armenian man, has lost touch with her relatives in Baku. They have not spoken to each other for many years.

Nazli Gasparyan, who took on her husband’s surname after marrying him in 1978, remembers the times when Armenian and Azerbaijani people lived side by side.

‘Many people were against our marriage’, Nazli tells OC Media. Her mother-in-law did not want her son to marry an Azerbaijani woman, but when her husband came home with her, she accepted her, saying ‘what a beautiful Azerbaijani girl you brought, my son’.

Travelling to Armenia and Azerbaijan

Sometimes, mixed couples living in Georgia have the chance to travel to each others’ countries. For example, an Armenian woman married to an ethnic Azerbaijani is able to travel to Azerbaijan if she has her husband’s or a Georgian surname. Some are able to go to Azerbaijan with their husbands, even taking part in weddings and other celebrations.

Leyla (not her real name) told OC Media that only close relatives know about her Armenian heritage, but in general, the family keeps this secret. Leyla has been to Baku and visited the Armenian Church and the Armenian district there. According to her, the city’s elderly still use the old names of the districts. ‘I really liked the city and hope that my husband can one day see Armenia as well’, she says.

Leyla’s husband Ali also wishes to be able to travel in the region. ‘I hope one day we can go freely to Armenia and Azerbaijan together, without fear of being targeted based on our ethnicity’, he tells OC Media.

Ali’s and Leyla’s love was born in Ortachala, one of the oldest areas of Tbilisi, known for harmonious cohabitation of different nationalities. Ali’s visit to a hairdresser proved crucial. ‘From that day on, the first three letters of my numberplate have been three letters of my wife’s name’, he says, pointing to a car parked at the end of the street.

Food, language, religion

Armenian–Azerbaijani mixed families in Tbilisi often maintain traditions from all three cultures — Georgian, Armenian, and Azerbaijani. They usually speak four languages: Georgian, Azerbaijani, Armenian, and Russian, visit both mosques and Armenian churches, prepare and eat Georgian, Armenian, and Azerbaijani dishes.

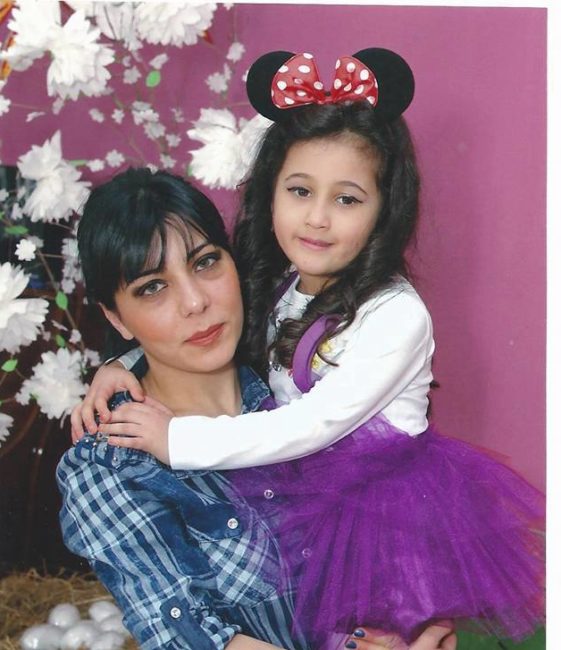

Zemfira works at a small bakery in the suburbs of the city, making Armenian bread — lavash. She takes home fresh lavash every day and her mother-in-law often prepares Azerbaijani plov (pilaf). ‘I want our daughter to know both cuisines’, says Zemfira, who attends both the mosque and the Armenian church with her daughter, who at age six has already decided that she is Muslim.

Most mixed families celebrate Azerbaijan’s Novruz and Armenian and Georgian Easter with all national dishes on the table.

Kristina, whose mother is Azerbaijani and father is Armenian, says that tolma/dolma (meat wrapped in vine leaves) is the only cause for fighting in her family.

‘My father says that tolma is Armenian, while my mother insists it is Azerbaijani’, explains Kristina smiling. To her it doesn’t matter who a particular dish belongs to’. ‘What’s important is that it’s delicious’, she concludes.

Kristina, who speaks four languages, says she has three identities. She remembers that her parents were never able to speak confidentially in her presence, because she could understand all the languages they knew. ‘I feel rich with all of this’, she says.

Thirty-two-year-old Inna (not her real name), told us that sometimes she has to hide her Armenian background.

‘Once, my husband’s relatives and friends came to Georgia on holiday and visited us. During a conversation (in Russian), I tried to conceal that I am Armenian but my seven-year-old daughter said, “mum, but you are Armenian aren’t you?” ’, Inna recalls.

She was able to change the topic and thinks that their guests did not pay it any attention.

Inna, who works with her husband on a central street in Tbilisi, uses Azerbaijani to present her goods — souvenirs and natural juices — when she sees travelers from Azerbaijan or Turkey. When an Armenian approaches, she uses Armenian. However, she mostly presents herself as Georgian.

Raising the children

Nazli’s husband Styopa Gasparyan was caught by surprise when he found out that his wife speaks Azerbaijani with their children. ‘I thought my children were Armenian, but they did not know [that] language first. But as we know, children learn languages quickly and so they began speaking four languages at the same time. My wife also speaks Armenian better than I do’, says Styopa.

According to Nazli, nationality does not cause arguments in her mixed family, however one thing has tormented her for a long time.

She adopted Christianity after her children were baptised at an Armenian church, but she has a lot of regret, saying that ‘that day changed my life for the worse. Perhaps, God punished me’.

Nazli now wants to re-adopt Islam, but this creates a number of questions. ‘They will tell me [a prayer] which I will repeat in the mosque and I will return to my previous religion, but I worry that when I die as a Muslim, my family will not be buried next to me’.

‘I love and respect both my father’s and my mother’s national traditions, I have an Armenian surname, I am Christian’, says Nazli’s daughter, Gohar, adding that religion should never be changed.

‘God is one’

Erik Mamedzadeh, born to an Azerbaijani father and an Armenian mother, says he ‘burns candles both in the mosque and in Armenian, Georgian, and Russian churches. God is one’. There is a corner in his room where Christian and Muslim religious symbols hang side-by-side on the wall.

He runs a Caucasian rug and antiques shop that he says is like the ‘old Caucasus’, where tolerance and cross-border spirit was so natural and cherished in Old Tbilisi. ‘Blessed were the good times’, he says, wishing the good times would come back.