The Central Election Commission of Abkhazia (CEC) has proclaimed opposition leader Aslan Bzhaniya the winner of Sunday’s presidential election.

Bzhaniya leads the Amtsakhara Party, which led a larger opposition coalition in the vote.

He will serve as a President for the next five years with his running mate, former Minister of Culture Badra Gunba, to become Vice President.

On 20 March, Bzhaniya indicated he was considering third President of Abkhazia Aleksandr Ankvab as prime minister. The government cabinet in Abkhazia is led by the PM.

According to the CEC, Bzhaniya garnered 54,000 votes (57%) in the 22 March poll, followed by current Vice Prime Minister Adgur Ardzinba with 34,000 (35%) and former Interior Minister Leonid Dzapshba with just 2,100 votes (2%).

Bzhaniya, a former head of Abkhazia’s State Security Service (SGB), replaces Raul Kkhadzhimba, who had served as president since 2014 after ousting Ankvab from power through street protests.

Abkhazians voted in 154 election precincts, including one each in Moscow and Cherkessk, the capital of the Russian Republic of Karachay–Cherkessia which borders Abkhazia to the north.

The CEC put turnout at 72%, over the 50% needed for the vote to be valid.

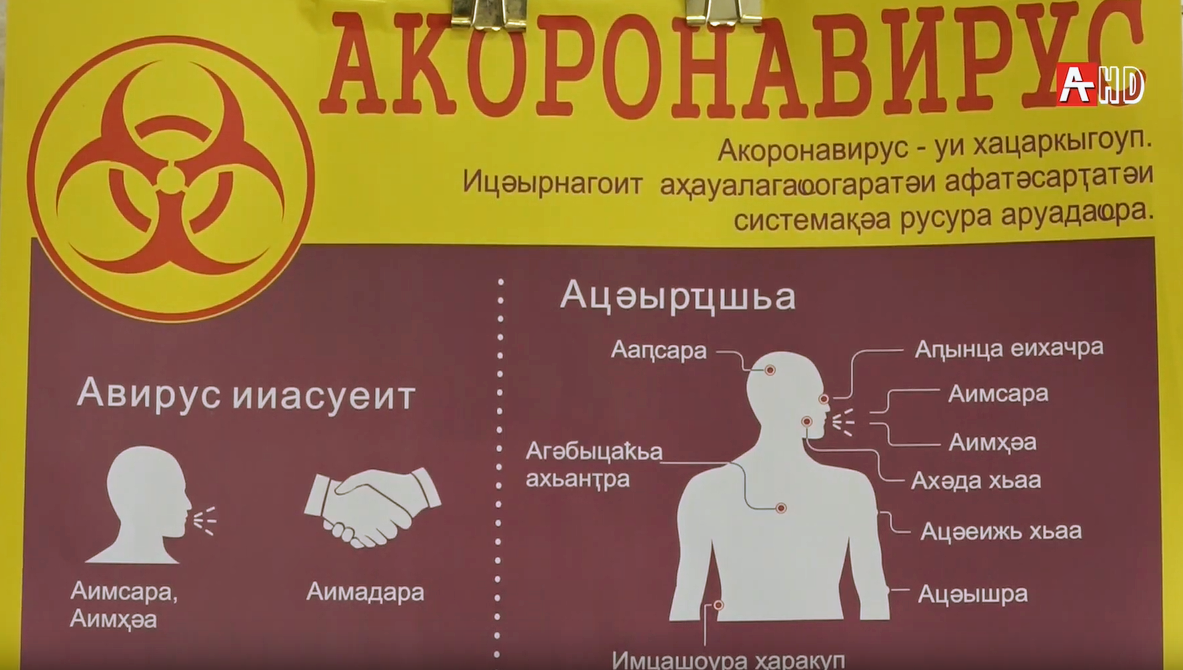

An election amidst the Coronavirus pandemic

Sunday’s vote was held amidst a global coronavirus pandemic.

The Abkhazian authorities tried to minimise the public health risks by giving polling station staff medical masks. They also asked voters to bring their own pens to the voting booths to avoid possible contamination.

Local media reported the measures were not always observed.

After voting in the Tamysh precinct on Sunday, Bzhaniya embraced members of the precinct’s administration.

A ban on public meetings and events enacted on 12 March also did not include election campaign events, which at times had candidates meeting with voters in packed venues.

On 14 March, Abkhazia also closed crossing points with western Georgia’s Samegrelo Region due to the threat of the virus.

On 18 March, Abkhazians not holding Russian citizenship found themselves blocked from entering Russia following a decision by the Kremlin to ward off the spread of the coronavirus.

Earlier this month, Abkhazia received two shipments of technical and medical aid from the UN, personally delivered by Louisa Vinton, Resident Representative of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Georgia.

[Read more on OC Media: Abkhazia and South Ossetia scramble to prepare for coronavirus]

Observers and foreign policy

The election was observed by fewer foreign missions than in previous polls. Members of Russia’s State Duma, Federation Council, and Russian Central Election Commission were absent, replaced by a handful of representatives of the Russian the Embassy in Sukhumi.

The only other international observers were part of South Ossetia’s and Transnistria’s delegations.

Georgia’s foreign ministry, which has not recognised any elections in Abkhazia since losing control over it during the 1992–1993 military conflict, denounced the vote on 22 March, calling it ‘illegal and fully contradicting international law’.

The election was also condemned by a number of Georgia’s strategic partners and western allies, including the Group of Friends of Georgia in the OSCE.

Only Russia and four other UN member states (Syria, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Nauru) recognise Abkhazia as independent.

All organised political groups in Abkhazia support Abkhazia’s political independence and closer relations with Russia. An overwhelming majority is also critical of what is frequently understood as efforts by the Georgian authorities to impose an ‘economic blockade’ on Abkhazia, and restricting the movement of Abkhazians outside Abkhazia.

However, during television debates on 20 March, both Bzhaniya and his rival, Adgur Ardzinba, reiterated a need to ‘talk with Georgia’.

The only formal talks between Georgian and Abkhazia officials currently take place as part of the Geneva discussions, which were set up following the 2008 August War and are co-chaired by the EU, OSCE, and UN. The talks involve Georgian, Russian, Abkhazian, and South Ossetian negotiators, as well as the US.

Speaking to journalists on 23 March, Bzhaniya said that in parallel to the Geneva format, Abkhazian and Georgian authorities needed a separate platform for bilateral talks on ‘problems related to border’.

In a 2018 interview with OC Media, Georgian Minister for Reconciliation Ketevan Tsikhelashvili said she had previously reached out to Abkhazian officials to open up a new line of talks, but was ‘still waiting for reciprocity’.

‘When it comes to us talking outside Geneva, all I’ve seen for years is that those talks are being hampered by Russia’, Tsikhelashvili said.

Following the final results, Russian President Vladimir Putin was quick to congratulate Bzhaniya on his victory.

A year of political turmoil in Abkhazia

The vote follows a period of political turmoil in Abkhazia, which has been trying to elect a president since early 2019.

The vote was originally scheduled for 21 July, however, in April, Bzhaniya fell seriously ill, leading supporters to claim he had been poisoned.

In May 2019, President Raul Khadzhimba gave in to protesters and postponed the vote until August.

As he had still not fully recovered by August’s vote, Bzhaniya was replaced by political ally Alkhaz Kvitsiniya.

After coming second in the first round and losing September’s runoff vote by 46% to 47%, Kvitsiniya led a 4-month campaign to overturn the results, arguing that as neither candidate gained more than 50%, the election lacked legitimacy.

On 10 January the Supreme Court of Abkhazia upheld Kvitsiniya’s complaint scrapping the September results. Then-President Khadzhimba’s resignation followed within days.

Three weeks before Sunday’s vote, Bzhaniya fell seriously ill once again, in Sochi, a city in Russia’s Krasnodar Krai. He continued his campaign from mid-March.

This again led to accusations he was poisoned and was followed by anti-government street rallies.

Issues and tactics of political change

Due to several high profile cases of kidnapping and attacks in recent years, fighting organised crime was one of the central topics of the election campaign.

Khadzhimba’s final months of rule were also marred with a similar case. A member of his security detail was involved in a shootout in Sukhumi in which a relative of Akhra Avidzba was killed.

Avidzba, who is recognised as a hero by the Donetsk People’s Republic, was among the strongest voices leading the charge in January upheavals that pushed Khadzhimba to resign.

On 9 January, a day before the Supreme Court annulled September’s results, opposition groups stormed the presidential Administration building and then gathered outside the president’s residence demanding the results be cancelled.

Another widely discussed topic was ownership of the Enguri (Ingur) Hydroelectric Power Plant, which generates electricity used in Abkhazia and throughout Georgia.

Other topics included ecological concerns over and economic prospects of oil extraction, citizenship policy and integration of ethnic Georgians in the Gali District, and fighting corruption.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.