Ahead of Georgia’s 4 October elections, the already fragile opposition split further — not over joint candidates, but over whether to take part at all. Irakli Kupradze, the joint Tbilisi mayoral candidate of opposition groups Lelo — Strong Georgia and For Georgia, is firmly committed to running.

‘After a boycott, would I be stronger as a structure, as an opposition party, or weaker? The clear answer is that […] the parties that boycott will end up weaker’, Kupradze tells OC Media during an interview recorded at his party headquarters.

The 30-year-old Secretary General of Lelo was nominated by two groups in mid-August, just a month and half before the elections.

‘Running for mayor of Tbilisi was never part of my plans’, he says, noting that what he had planned was a ‘broader fight’ against the Georgian Dream government, referred to by him, like many other opposition figures, as the ‘Russian regime’.

What prompted him to change his plans, Kupradze says, was a poll his party commissioned among Tbilisi residents, testing several potential candidates.

‘This poll, along with the political context, pointed to a specific candidacy — and that was me’, he adds.

Originally from the Black Sea city of Batumi, Kupradze first entered public life as a student activist in left-wing movements before joining Lelo in 2019 — the party founded by TBC Bank co-founders Mamuka Khazaradze and Badri Japaridze.

His move at the time prompted questions among his leftist peers, to which he responded that he had been welcomed into the party ‘as a leftist’, portraying Lelo as an ideologically diverse political group.

Six years on, he once again finds himself having to justify his decisions — this time to a much wider audience.

‘The struggle always matters’

Unlike a classic pre-election campaign, Kupradze’s mission is not only to convince voters to cast their ballots for him, but to persuade them to turn out at all.

After the October 2024 parliamentary elections, which were marked by major violations and resulted in Georgian Dream’s disputed victory, all major opposition groups — including Lelo — boycotted parliament and rejected the legitimacy of the ruling party.

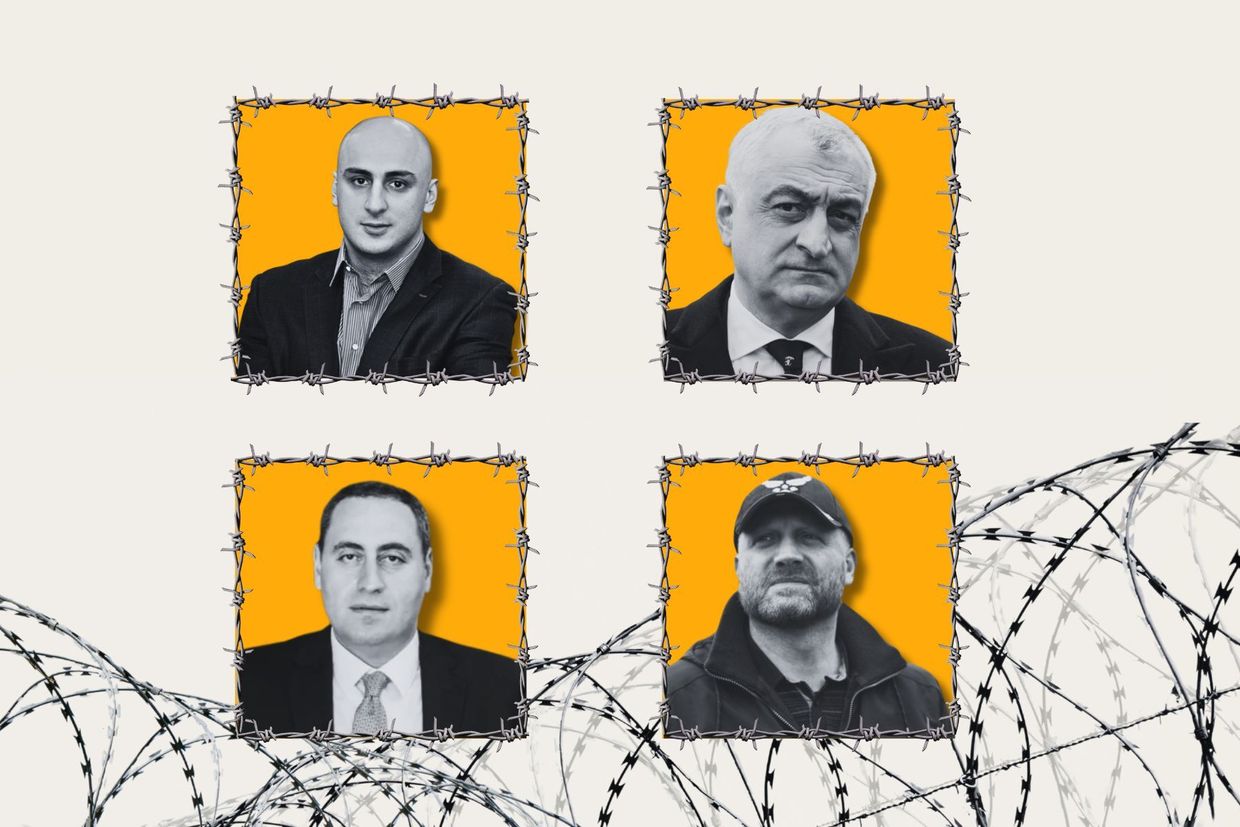

Since then, the democratic backsliding has only worsened: Georgian Dream first suspended the country’s EU membership bid before responding to large-scale demonstrations with brutal police violence. The ruling party then passed a series of repressive laws against critics and jailed opposition leaders, including Lelo’s founders, for not cooperating with its anti-opposition parliamentary commission.

Daily anti-government protests are still ongoing, with eight opposition parties — including the two largest opposition coalitions Unity — National Movement and the Coalition for Change — planning to boycott the municipal elections and calling on their supporters to do the same.

Lelo chose a different path, as did For Georgia — the party founded by former Georgian Dream Prime Minister turned opposition leader Giorgi Gakharia. Both decided to participate in the elections with joint candidates.

‘The struggle always matters’, Kupradze says when asked why they rejected the boycott.

Kupradze and his allies are convinced the ruling party would have preferred no opposition party to enter the race.

‘[Georgian Dream] is not afraid of running alone’, he says.

He explains that one reason Lelo confirmed its participation in the elections relatively late — in July, just three months before the vote — was the lengthy process of trying to persuade other opposition parties:

‘We made enormous compromises on our side […] but certain opposition parties refused to engage in this kind of struggle’.

What Kupradze calls a ‘struggle’ is viewed by many in the opposition as a betrayal — not only of the drive to delegitimise the ruling party, but also towards the jailed protesters and the demand for new parliamentary elections.

Kupradze does not share this interpretation. He argues that Georgian Dream’s legitimacy was already voided when opposition parties renounced their parliamentary mandates after the disputed elections.

‘Local elections can in no way be connected to the source of national legitimacy, which lies in parliamentary elections and the transfer of power through them. Who becomes mayor of [the town of] Kaspi has nothing to do with whether the government is legitimate at the central level’.

Nor does he believe that taking part in the municipal elections means forgetting about the imprisoned protesters — among them his fellow party members Vepkhia Kasradze and Vasil Kadzelashvili:

‘Will refusing to run in the municipal elections set political prisoners free? If there are no opposition or critical voices at all in local councils or mayor’s offices, will that help secure, for example, my friend Vepkhia Kasradze’s freedom, or make it harder?’

According to Kupradze, around 80% of Lelo’s political council accepted this line of reasoning, though not all: after the party confirmed it would contest the elections, several prominent members resigned.

‘We respect their views too, but any political party makes decisions by majority’, Kupradze notes.

Asked how he would deal with the central government — whose legitimacy he does not recognise — if he were to win, Kupradze responded:

‘If I win, I will have to engage in radical confrontation with the central government […] There are more than 40,000 public employees in Tbilisi. My mayorship would give those 40,000 officials the chance to freely express their own opinions’.

According to Kupradze, his victory would also benefit anti-government demonstrators, who gather daily in the city centre and face hefty fines for blocking roads, as well as periodic detentions:

‘If I were Tbilisi’s mayor, I would issue a permit every evening for a sanctioned rally on Rustaveli Avenue, so that the authorities could neither resort to force nor impose fines’.

Complicated numbers

While speaking with OC Media, Kupradze repeatedly cites figures that, in his view, strengthen the grounds for opposition participation in the elections — especially in Tbilisi.

One such figure comes from a survey by the Institute of Social Studies and Analysis (ISSA), with which Lelo cooperates. A June poll showed that, excluding those who did not express a preference, Georgian Dream’s support in the capital stands at only 23%.

‘Georgian Dream and Kakha Kaladze have 23%, while the pro-Western opposition has 70% or more. How, under these conditions, can you not fight?’ he asks.

‘[Georgian Dream] would literally have to shoot us down with armed men at polling stations, steal the ballot boxes, and cancel entire precincts or they’d have to concede’, Kupradze adds, pointing to the difficulty of manipulating the results in the capital.

However, the picture is not as clear-cut as the aforementioned figure suggests.

First, according to the same survey, more than a third of voters remained undecided or took a nihilistic stance both in Tbilisi and nationwide. A further — and perhaps even greater — challenge for Kupradze and his teammates is that only 20% of pro-Western opposition supporters backed taking part in the municipal elections unconditionally, that is, without the announcement of new parliamentary polls.

Even among Lelo’s supporters, fewer than 40% said they were certain to cast their ballots on 4 October, while among For Georgia’s supporters, the figure was at 46%.

So how does Kupradze plan to persuade both his own supporters and those of other opposition parties to turn out — especially given that the two largest opposition groups are calling for a boycott?

‘Through constant communication and dialogue with the [voters]’, Kupradze says, emphasising that he appeals to ‘Tbilisi’s opposition-minded, pro-European citizens’ in general, not only the two party’s voters.

‘[I’m appealing to them] by explaining what outcome each path leads to. The path of boycott means that [Georgian Dream founder] Bidzina Ivanishvili will be able to fully consolidate power in 64 municipalities, tighten his grip on finances, the budget, and administrative resources, and bring local councils under complete control without any resistance’, he adds.

Kupradze also says that in ISSA’s latest, unpublished survey, the share of those supporting unconditional participation in the elections had risen.

‘It will definitely [continue to] rise, because the futility of a boycott is very easy to see’.

‘These will not be fair elections, but…’

When the Lelo–For Georgia alliance announced Kupradze’s candidacy on 18 August, the slogan ‘Let’s reclaim our cities and villages together!’ was displayed on a screen behind him.

The alliance views Tbilisi as a central battleground in the election, with Kupradze’s phrase ‘we should wrest Tbilisi away from Bidzina Ivanishvili’ becoming an even more recognisable line of his campaign than the official slogan — in part due to the ridicule and sarcasm it has drawn from boycott supporters.

From the perspective of the latter, both Kupradze and the other candidates from the two parties are playing a game whose outcome is already decided: following the disputed 2024 elections and subsequent political developments, they do not believe that fair elections are possible under Georgian Dream and the current electoral administration.

Kupradze agrees that the vote ‘will not be fair or democratic’, though he also once again stresses that a boycott is not the solution:

‘He [Ivanishvili] wants to abolish parties […] If we abolish ourselves and hand Bidzina Ivanishvili a clear path without any resistance, I don’t think that’s the right approach’.

Kupradze does not specify a concrete minimum threshold that would make him consider the resistance he mentioned a success. In his words:

‘Any attempt to take even part of Ivanishvili’s power away is valuable to us’.

But what does he mean by ‘taking away’?

‘Everything is taking away: however many councillors you take, however many mayorships you take, it all weakens [Ivanishvili], [while] allowing him to act freely according to his own will only strengthens him’, Kupradze says.

Lelo’s social media has frequently featured materials about meetings with the public on the streets of Tbilisi, as well as about the priorities of their electoral programme — including unsafe housing, problems faced by the elderly, drug policy, environmental protection, and the plight of stray animals.

Critics contend that the campaign is out of step with the broader political climate and appears misplaced at a moment when Georgian Dream’s escalating repression threatens the core principles of democracy.

For his part, Kupradze argues that defeating the ruling party is impossible without addressing people’s everyday problems. At the same time, he believes that success in the municipal elections would strengthen opposition forces in the push for new parliamentary elections — which, he is convinced, Georgian Dream will eventually be forced to call.

‘The opposition is stronger when it has structure — strong, well-resourced councillors on the ground who represent the needs of society. That includes local leaders. If you don’t give local leaders this opportunity, the whole thing collapses,’ he explains.

The integrity of the 4 October elections is further clouded by challenges to election monitoring. Against the backdrop of legislative pressure on civil society, one of Georgia’s largest election watchdogs has already announced that it will not field an observation mission this year.

In addition, breaking with tradition, even the OSCE/ODIHR will not observe, citing Georgian Dream’s last-minute invitation as making ‘meaningful observation impossible’.

Lelo and For Georgia seek to fill this gap with their own resources.

‘[Lelo] will have around 6,000 representatives at polling stations across the country’, Kupradze says.

‘We will try to avoid repeating the mistakes the opposition as a whole made [in 2024]’, he adds, stressing the importance of ‘gathering more evidence on the schemes’ the ruling party uses to manipulate elections.

The municipal elections will take place against the backdrop of open threats from the ruling party to ban all major opposition groups — regardless of whether they contest the vote or not.

Georgian Dream plans to petition the Constitutional Court on the basis of its anti-opposition commission’s conclusions, which brand every major party, from the former ruling United National Movement party (UNM) to Lelo, as engaging in anti-state activity.

What will happen if the parties are banned and the seats won in the municipal elections are left with no value?

‘We will find new ways to continue the struggle — both in the streets and within the political process. There is no scenario, no matter what Ivanishvili does, that will make us abandon the fight against him’, Kupradze says.

Moreover, he argues that ‘if anyone is stuck in Kaladze’s and Ivanishvili’s throats like a bone they cannot swallow, it’s us — because we are in active resistance’.

Shortly after the interview, Georgian President Mikheil Kavelashvili — whose legitimacy is also questioned by critics — pardoned Lelo leaders Khazaradze and Japaridze, explaining the decision by citing their participation in the municipal elections.

Boycott supporters interpreted Kavelashvili’s move as confirmation that Georgian Dream sees Lelo’s involvement as providing legitimacy to the vote. The newly released leaders disagreed, noting that the president’s ‘cunning’ decision is yet another attempt to sow divisions within the opposition.

Following the release of its leaders, Lelo reaffirmed that its decision to participate in the elections would not be reversed.