As fighting in and around Nagorno-Karabakh continues to flare up, talk of peace in Armenia is often subject to harsh criticism. Nevertheless, some activists are turning to feminism and mutual dialogue to prevent another large-scale war.

Two months after the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War came to an end, Anahit Baghdasaryan chanced upon Caucasus Crossroad, a Facebook group created by Azerbaijanis and Armenians to provide a safe space for dialogue between people of either nationality.

With news trickling down from Nagorno-Karabakh about ceasefire violations, gas supply problems, and reports of villages being taken by Azerbaijan, Anahit believes that the lack of direct communication between either side can only cause further strife.

‘I think there is no alternative to talking about peace’, Anahit says. ‘We cannot sit and threaten each other for 10, 30, or 50 more years. It is important to talk about peace — especially now’.

Anahit eventually became a moderator in the group, grasping at any opportunity to talk to people from different backgrounds, however unpleasant the conversation might be.

Having come from a family that was directly affected by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Anahit never feared being branded a ‘traitor’ for her online activism; her mother was a refugee from Azerbaijan, while her husband, her father, and her brother all served in the military during the 44-Day War.

Anahit never tried to stop her loved ones from enlisting, though she never encouraged it either, stressing that it was their decision to fight — they all came back home safe, although her brother was injured during the fighting.

To her, the sacrifices her family has made for ‘the cause’ provided her with the freedom to be vocal about peace, and though Anahit did not have any ideological disagreements with her husband, he was bothered by the amount of time she spent on the group.

‘I fought for it, it was my right to be there, and I needed to talk to the people in that group’, she says.

‘I am not a blogger or a public figure, but I had friends reading my posts, it showed me that these ideas could be voiced, I could say it without being afraid’.

As the conflict continued to loom large over the Armenian conscience, Anahit recalls how some of her female friends shared pictures of Monte Melkonyan — a popular Armenian resistance figure who fought in the first Nagorno-Karabakh War — with captions reading ‘don’t drink for me, continue my work’.

‘I sit and think about what kind of messages they send to men who are reading them; they make them think: “this is the ideal man, one who is fighting”.’

‘In reality, those guys want to go to university, they want to date, they don’t want to go to a war and die’, Anahit says. ‘But they sell us these ideas periodically, even the mothers [of soldiers who died] who appear in video reports are most often those who will say they are proud of their children for giving their lives to their country.’

As a mother of two boys, Anahit says she felt this pressure herself, often being accused of putting her motherly instincts before her nation.

‘Society demands loyalty from me because they need my children. They want me to raise them as patriots.’

‘If the rights of a woman are protected, if she is not oppressed, and if she feels self-sufficient, she would not need a “strong and cool guy” beside her to be assertive’, she says, adding that these are the factors give women the opportunity to talk about peace.

‘We still wake up to news of soldiers being killed on the border’

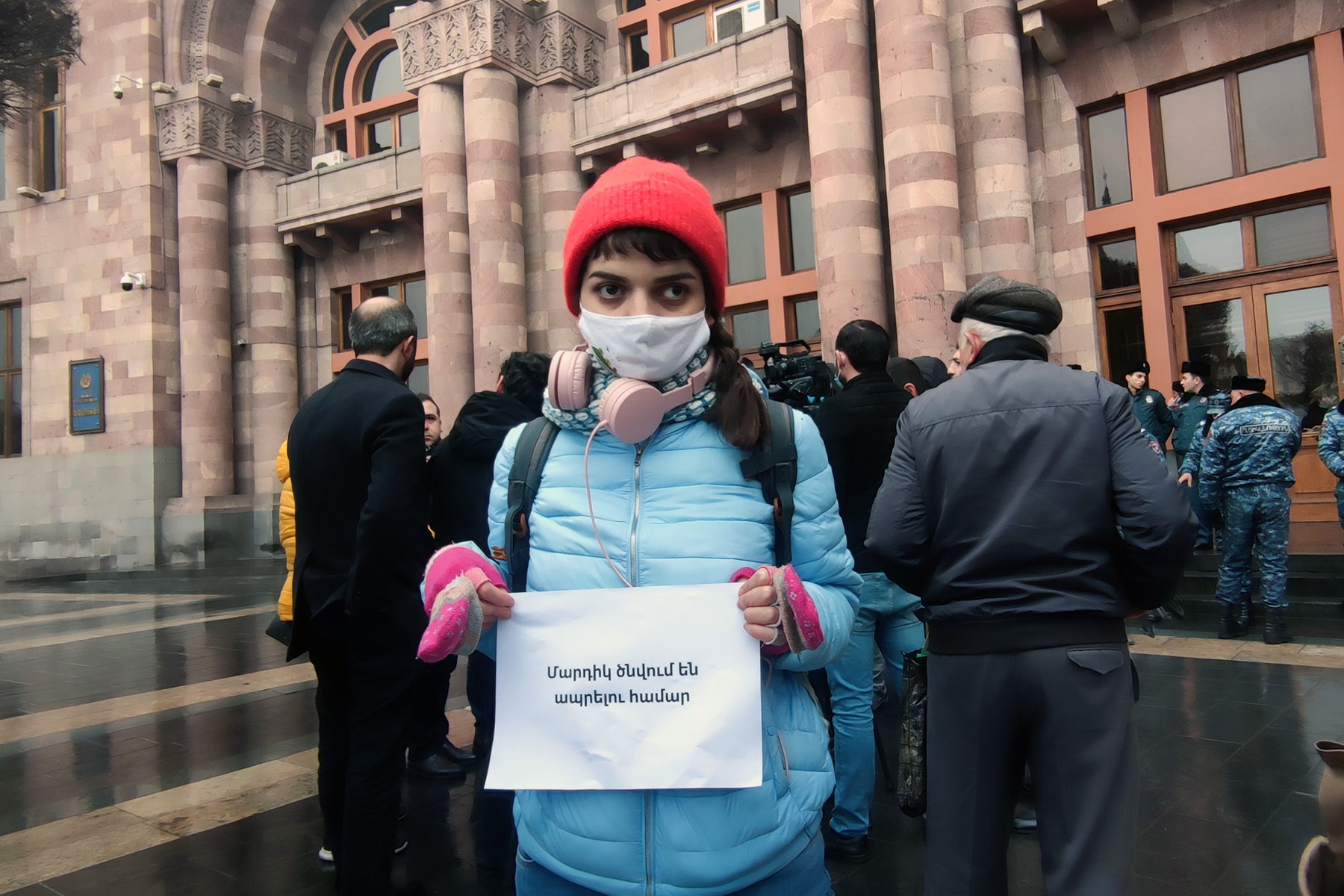

On 13 January, a group of activists, mostly women, organised a protest in front of the government headquarters in Yerevan against the continuously rising death toll of Armenian soldiers during what the authorities referred to as the ‘Era of Peace’.

Signs and placards handed out during the demonstration read ‘women against the meat grinder’ and ‘mothers are waiting for their children’.

Human rights activist Zaruhi Hovhannisyan, who attended the demonstration, says they took to the streets to show the government that women were not at peace with the death of Armenian soldiers, and to bring attention to ‘the right to life’.

‘People should not be at peace with the violation of the right to life. This is a country, where they dig graves with [heavy] equipment while they dig trenches with hands and shovels, which is unacceptable. We have to do everything so that those children’s lives are not the cheapest thing’, she says.

Zaruhi says that the public trusted the government during the 44-Day War, as information from the front lines came directly from centres of authority in Armenia.

‘People were thinking that every possible thing was being done to ensure the right to life, and that deaths were not a cause of lack of organisation, but rather that they came as a result of the scale of the attack. People were silent and stunned from grief, but now we are in the phase when we try to return to a more rational life, and yet we still wake up to news of soldiers being killed on the border’.

Enabling women and the fight against patriarchy

In Helsinki, Marina Danoyan, a peacebuilding practitioner, highlighted the psychological effect of war on people, describing it as a ‘collective trauma’ that potentially has the ability to discourage people from speaking up against it.

‘Emotions are so overwhelming during wartime that it is very hard to stop yourself and find the strength to think differently or gather others around you.’

Marina stressed the importance of empowering women who have lost loved ones by providing them with training and opportunities for employment.

‘If the women are working, they find the strength within themselves, they realise that they have what it takes to take care of their family, and it will fill their life with positive energy which can be passed on to their children and society’.

As fighting around Nagorno-Karabakh and along the Armenian–Azerbaijani border continues, Shushanna Tevanyan, a graduate of the University of San Diego School of Peace, criticised the ambiguity of the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh.

‘I don’t know what stage our conflict is at right now’, she says. ‘I cannot understand at all what is going on; if there are any negotiations now or not; if the sides are working together in any way or not; if Azerbaijan’s policy now is the ethnic cleansing of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh or not; or whether or not Armenia would allow that to happen. Why do Russian [peacekeeping] troops let Azerbaijan take new villages? I do not understand anything’, she asked.

Around 2,000 Russian peacekeepers were deployed to Nagorno-Karabakh as part of the agreement that brought an end to the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.

On an internal level, Shushanna described the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the negotiations around it as a question that was, unfortunately, out of society’s reach.

‘[Civil society] has let the state decide what to do, and the state had the monopoly on the conflict’, she says.

Shushanna went on to criticise how feminism often overlooks how men are also victims of the patriarchy, casting blame on conscription for creating endless cycles of violence in societies.

‘Our feminists imagine women’s problems and men’s problems as separate from each other’, she says. ‘Why do men become violent? A lot of times the root of this goes back to the army’.

‘The state doesn’t provide them [men who serve in the army] with emotional support, and they do not learn how to deal with all the violence they witness, so they turn it into violence again and it becomes a cycle. If you are fighting against the patriarchy, well men are its first victims. Isn’t the army a patriarchal structure?’

Being from the southern Armenian region of Syunik, which saw border clashes with Azerbaijan following the end of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, Tevanyan said that the women who lived in the villages in the province had always surprised her with their pragmatism and wisdom.

‘Many mothers understand that their sons died because of incorrect political decisions, incorrect diplomacy,’ says Shushanna. ‘It is important to make sure these peoples’ voices are heard as well. If people know about these parents, if society hears their stories, it will be a good motivation for them to realise that even a person who has lost a son is talking about peace.’

‘Because there are so many people who didn’t lose anything but are still warmongering online’.

‘Why aren’t the voices of these people heard? So what if they live in villages?’ Shushanna asks, stressing the importance of listening to the most vulnerable groups — including borderline populations and refugees.

As uncertainty clouds the conflict, Shushanna, like many others, continues to question the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh should Russian peacekeepers withdraw from the region.

‘There could be a new war, there could be ethnic cleansing, there could be a huge flow of refugees coming to Armenia from Nagorno-Karabakh’, Shushanna speculated.

Yet she still maintains that first and foremost, dialogue is necessary. ‘Peace talks won’t lose their value, because peace would mean that people are no longer dying from armed conflicts, that there will be a political structure preventing the conflict from turning into war again’.