After 73 years, the memory of Stalin’s deportation of Chechens and Ingush still haunts the survivors

The twenty-third of February 2017 marks 73 years since the mass deportation of Chechens and Ingush from their homelands to Central Asia. Stalin’s Soviet Union ordered the deportation in the winter of 1944, following which, the Chechen–Ingush Oblast was fully abolished. Every year, Chechens ask why it had to happen. The question has remained unanswered.

The twenty-third of February 2017 marks 73 years since the mass deportation of Chechens and Ingush from their homelands to Central Asia. Stalin’s Soviet Union ordered the deportation in the winter of 1944, following which, the Chechen–Ingush Oblast was fully abolished. Every year, Chechens ask why it had to happen. The question has remained unanswered.

‘Operation Lentil’ was the name given to the secret plan to deport the Vainakh peoples (Chechens and Ingush) en masse. To implement it, up to 150,000 personnel from the military and NKVD (the Soviet secret police) were brought from the frontlines to Chechnya and Ingushetia, then united under one oblast.

Days before the operation began, soldiers were distributed throughout all settlements in the oblast. Local people, unaware of the real reason for their arrival, received them as guests.

‘My mum would tell the story about how she was 11 at the time and she was chopping wood in the yard. A soldier saw her and said: “Don’t bother to chop so much, don’t bother”. On the next morning, these soldiers with machine guns brought all the people to the centre of the village, from where they were transported by lorry to train cars meant for cattle. This is how the long journey to Kazakhstan began’, says Yuni Uspanov, a resident of Chechnya.

The operation, which began on 23 February, was concluded by 9 March. While transporting people from the lowland regions to train stations went relatively smoothly, the expulsion of people from highland areas involved extreme cruelty. Inhabitants from the many villages with no roads leading to them were forced to march through the snow. The old and the sick were shot on the spot or bayoneted. People who rushed to help them were instantly killed by machine gun fire.

Asluddi Tsugayev, a 92 year-old native of Khoy, in the Vedeno District, recalls how he had to walk 30–40 km to Kharachoy under the soldiers’ escort. Not everyone could make it.

‘As they were leading us down a cliff, an old man walking at the end of the column fell to his knees and put his hands on the ground. He couldn’t go on. He was bleeding from his mouth. His daughter and son, threatened with rifles, were herded back into the column. Someone in the crowd threw him a piece of cornbread, so he wouldn’t die of hunger. After we walked a bit farther away, the soldiers shot him and kicked his body down the cliff. I still have the sight of this old man in my eyes. He was surprised by the animalistic cruelty of these people who drove him out of his house’, Tsugayev recalls.

Akhid Khasayev from Urus-Martan District was six at the time of the deportation. He can’t remember much, but one event has been imprinted in his memory. His family was forced to walk from the village of Kharsenoy to the town of Shatoy; there was no road between them. On the way, they had to spend a night at a local cemetery. He recalls how people were collecting wood from the cemetery’s fences to make bonfires.

‘Our mother laid the four of us children on a burka [a Caucasian felt coat] spread between two burial mounds and covered us with a woollen blanket. She could cover herself only partially. It was very cold, but I still fell asleep. I woke up because something dripped on my face. I thought it was the melting snow and I tried to catch the water drops with my lips. When I looked up, I realised that these were the tears of my mother. She was leaning over us and crying silently’, Khasayev recalls.

In many villages, dozens were shot for refusing to leave or being physically unable to. The most infamous massacre of innocent people took place during the eviction from the remote mountainous village of Khaybakh, in Chechnya’s Galanchozh District. On the orders of Colonel Gvishiani, who led Operation Lentil, more than 700 people were locked in a stable and burnt alive. Most of them were old men, women, and children.

Russia doesn’t recognise that the Khaybakh Massacre occurred, despite the dozens of testimonies from residents of neighbouring villages.

‘I heard that they burnt people alive in Khaybakh, but it was far away from our village — behind a mountain. We went there with several people. They’re not alive any more. When we arrived there, I saw something which can’t be described in words. I had seen a lot in my life, but it was unbelievable. People were burnt. The stables had collapsed on the bodies. People were lying under the crumbled ceiling. You could see broken skulls, body-parts. In the beginning we didn’t want to move them, but then we decided we couldn’t leave them like this. We built a stretcher and began to pull out the corpses. These weren’t really corpses, rather bones. Children’s bodies were fully scattered. Everything was burnt down. We kept finding fragments of legs, heads, and other parts of the body. We pulled everything out and behind a small river nearby we dug a ditch and buried the remains there. We recognised Tutu Gayev, he lived in Khaybakh, his face and beard survived, but the rest of the body was completely burnt. It took us two or three days to bury the bodies. We dug three of four ditches. Everything was in parts. There were no complete bodies. I saw it myself and I know’, says Saydkhasan Ampukayev, a resident of Achkhoy-Martan District.

The journey was especially difficult for the deportees. People were put in cattle wagons, which would stop on the way only to let people relieve themselves. Many women, especially young girls, died of ruptured bladders. During the stops, soldiers demanded they pass out the bodies of the dead. People were hiding them so they could bury them according to Chechen traditions. Still, many bodies were disposed of in the fields.

At the same time, 40,000 Chechens and Ingush — 10% of the population — were fighting on the frontlines for the country which was sending their nation to the distant steppes of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Many Vainakh soldiers were sent to Central Asia directly from the frontlines.

The late Adam Ladayev served in the Red Army from 1938 to 1941, including on the frontlines. He received multiple awards for his military valour. In 1944, he and all Vainakhs were declared enemies of the state. His awards were taken from him in front of other soldiers and he was sent to Ivanovo and later to Kazakhstan Oblast to fell timber. According to his son, Imran Ladayev, after returning from the deportation, his father denounced his military past and didn’t consider himself a veteran.

‘Until his death he couldn’t forgive the state for betraying him. He refused to receive even the high veteran pensions that were available. His resentment was stronger than the needs of his large family’, Imran says of his late father.

One third of the deportees died during the journey or in the first years of life in exile. Still, Chechens and Ingush managed to adapt to the new environment. However, the longing for their distant homeland became more acute every year. While greeting each other, Vainakhs would ask ‘Any news about the return?’ One Chechen publically declared that if they were allowed to return that year, he would fast every day for the rest of his life; this was in 1957. In this same year, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev signed a decree allowing the Vainakh deportees to return to Chechenya and Ingushetia. The man, originally from the village of Duba-Yurt, allegedly kept his word and observed the religious fast until the day he died.

Returning from exile wasn’t smooth either. All their houses had been occupied by Russian speakers and people from neighbouring Daghestan. Many Chechens had to buy back their houses for large sums of money. The Russian-speaking population was against the Chechens’ return. For this reason, major riots took place in the republic’s capital, Grozny, where demands were voiced to cancel Khrushchev’s decree.

Currently, the Chechen and Ingush people are attempting to tell the world about the genocide. Several years ago, the first feature film about the deportation was shot, financed by a Chechen businessman. As the film portrays the Khaybakh Massacre, the Russian Ministry of Culture banned it, arguing that the ‘alleged events have no documentary evidence’.

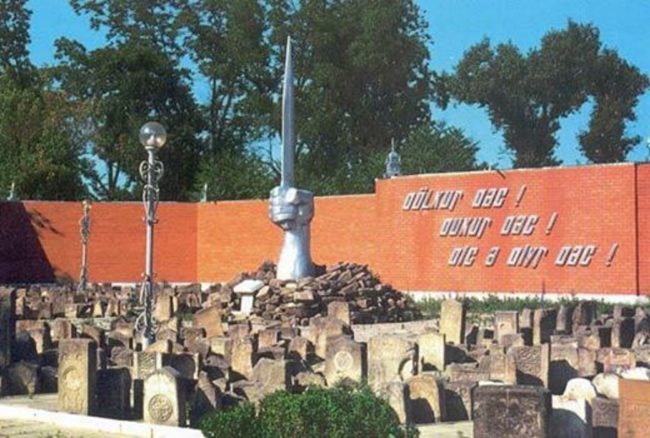

During President Dzhokhar Dudayev’s brief rule over the self-proclaimed Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was decided that the anniversary of the deportation would be remembered not as a day of mourning, but as the Day of National Revival. In the early 1990s, a memorial monument was erected in the centre of Grozny, dedicated to the victims of Stalinist repressions. The monument was composed entirely of old tombstones which in Soviet times had been used to build houses. The monument depicted a man’s hand, holding a dagger, sticking out from under the ground, with the Chechen inscription, Dukhur dats! Dölkhur dats! Dits a diir dats! (We won’t break! We won’t cry! We won’t forget!). The monument was dismantled in 2008.

According to official figures, more than 496,000 people were forcibly evicted from Chechnya and Ingushetia, 411,000 were sent to Kazakhstan and 86,000 to Kyrgyzstan. Other sources put the number much higher, at over 650,000. Chechen historians claim that about 400,000 people died during the eviction.

On 26 February 2004, the European Parliament recognised the deportation of 23 February 1944 as genocide.