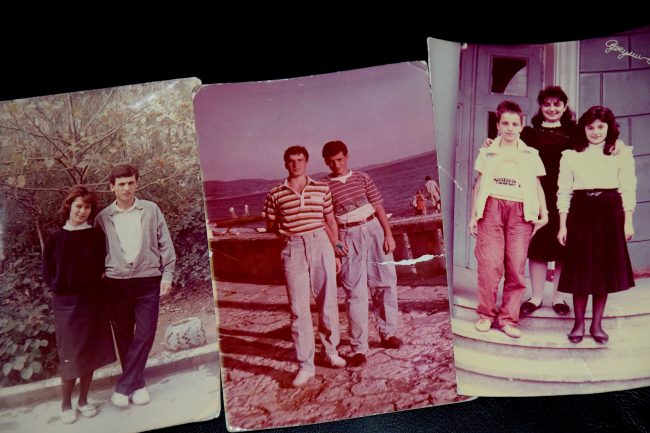

Some people’s hearts start to ache when they suddenly come across a photo album or an old video tape lying in dust in the corner of a cupboard. For a refugee from Abkhazia, the trigger is the word ‘war’.

Some people’s hearts start to ache when they suddenly come across a photo album or an old video tape lying in dust in the corner of a cupboard. For a refugee from Abkhazia, the trigger is the word ‘war’.

‘He came to his father, only a few days late’

Arshak Davidyan will never see Abkhazia again. The eighty-year-old refugee from the village of Tamysh, in the Ochamchira District, died last winter, alone, in a small room in one of the abandoned buildings of a former college, where he had lived for 24 years after leaving Abkhazia. He froze to death, to weak to light the fire in the stove.

During the war, many people from Abkhazia left their homes. Some moved to Russia, but Arshak Davidyan chose the Armenian-populated Akhalkalaki. He was given a room in one of the abandoned buildings of the college. When the college was replaced by Samtskhe–Javakheti University, he worked as a stoker. His former employees say he lost touch with his family and his only son during the war.

The tragic story of Arshak Davydian did not end there. According to staff at the university, Arshak’s son was alive, which became known the day after his death. He came to his father only a few days too late.

His belongings in his small, modest room, and a photocopy of the passport in the social service of the mayor’s office of Akhalkalaki, which paid for the funeral of Arshak Davidyan, is all that are left of him.

‘We could not go back’

Thirty-three refugees from Abkhazia have found new homes in Akhalkalaki. All of them have IDP status. In Akhalkalaki Municipality, there are refugees with Armenian and Georgian surnames from Gagra, Ochamchira, Gali and Sukhumi… In Akhalkalaki municipality, there are refugees living in Akhalkalaki and in the villages of Bavra, Chunchcha, Okami, Kulik. This status is automatically given to the children of refugees as well, who were born after their parents left Abkhazia. There are also many refugees who did not apply to local self-government bodies to obtain IDP status, and others who moved to other regions of Georgia.

The mixed Armenian-Georgian Tsurtsumia family settled in Akhalkalaki in 1993. Grigori Tsurtsumia is from Gali, and Gayane Tsurtsumia is a Hemshin Armenian from Sukhumi. Grigori and Gayane still cannot get used to the idea that they cannot go back home to Abkhazia, even though they are ready to leave everything, just to return home to Sukhumi.

‘I had a shoe shop, I remember going to work then (in 1992), and along the way our Abkhaz neighbours made a noise, the war had started, we were attacked. I thought Turkey had attacked us over the Black Sea. Georgia could not have attacked Georgians. We then took up arms to defend the interests of our country. We were shooting, we were shot at. In other words, we defended the territorial integrity of our country. This war was a great tragedy. Only then did we learn who the Abkhazians were, who the Georgians were, who the Mingrelians were. Before that, we did not think about who was who’, Grigori Tsurtsumia says.

The entire, large Tsurtsumia family moved from the warzone to Akhalkalaki in 1993, where there was nothing; no lighting, no bread, only a peaceful sky. The choice of location was due only to the fact that Grigori had relatives in Akhalkalaki.

‘My wife was pregnant. I took a vacation for three days, then I served in the Georgian army, and participated in military operations in Abkhazia. I brought Gayane here, left her with my relatives, my grandparents, and immediately returned. Even an absence of one day was considered desertion. Even one day mattered. When our company was disbanded, when the peace agreement was signed, the first thing I had to do was go to Akhalkalaki and see my son — I didn’t even know that our son had been born’, Grigori says.

‘We were going to return home. Then I went to the market in Akhalkalaki, met a soldier, we talked, and I found out what the situation there was, since we had no information here. He said that the fighting had began again in Abkhazia. When I had arrived, everyone was being demobilised, and I knew that the heavy equipment had been removed already… We could not go back’, Grigori Tsurtsumia says.

‘I did not return to Abkhazia’

Satenik Demurchyan was born in the village of Diliska, and her husband was from the village of Kulikam in Akhalkalaki Municipality. They moved to Abkhazia from their village, Atara-Armyanskaya, in the 1980s at the invitation of her husband’s friends, who found a suitable house for them there. The then-happy Demurchyan family had two houses there, and a big tangerine garden measuring one and a half hectares. Her husband left for Russia to work, and their family lived well, but everything ended in one moment, when the war started.

‘We lived there for several years, it was 14 August, the war had started. I was then 23 or 24 years old. The kids were five and six. We have a nice family, and we lived well, joyfully and peacefully. But we were unlucky. My husband died from illness. When the bombing happened, we didn’t have relatives around, so our neighbours helped. The whole village gathered, my husband was buried, and I was left alone with two small children on my hands. Afterwards, my brother-in-law somehow transported my son out of the village, and my father took my daughter. Then my parents took me. There were no [safe] roads, all of them were mined. We didn’t have the chance and were not allowed to go beyond the village. Somehow we got out from there, at night at 2:25 am we fled. We reached Krasnodar, where relatives helped us get to Akhalkalaki. After that, I did not return to Abkhazia’, Satenik Demurchyan says.

Demurchyan’s family left behind not only two houses and a tangerine garden in Abkhazia, but also the grave of the head of the family, which torments Satenik the most.

‘We ran away, basically wearing slippers. I will not go back, no. There is nothing there. Our house was ransacked, there are no doors, no windows, no roof. Everything was simply destroyed. Our neighbors showed us the ruins over the internet. I wouldn’t be able to start everything from scratch’, Satenik Demurchyan says.

‘We had to start from scratch’

The Asatryan family, like the Demurchyans, is from Akhalkalaki Municipality. Samvel Asatryan’s father is from the village of Khorenia, and his mother is from Bavra. Like some others, the Asatryans fled the war to Akhalkalaki because they had relatives there who could help them during this difficult moment. Many people from the Akhalkalaki Municipality have lived and still live in Abkhazia. Many have moved to Russia, mainly to Krasnodar Krai, while others returned to Akhalkalaki.

‘My father worked in Abkhazia, he bought a house there and we moved there to live. In the beginning, it was not very dangerous to live in Gali. It was quite diverse before: Russians, Armenians, Greeks, people of different nationalities lived there. When the war began, it was us, the children, who were sent away first. I was 18-years-old. We wanted to go back, but our parents came to Akhalkalaki. They said that the Abkhazians occupied Gali, so we decided not to go back. When there is a war, people don’t ask which nationality you are, Armenian or Georgian, everyone had a similar face, they didn’t ask what you last name was’, Samvel Asatryan said.

Each IDP receives benefits of ₾45 ($18) per month, this payment used to be ₾12 ($5). The Asatryans receive ₾135 a month for three people: the father, and the two children, who were born in Akhalkalaki. This is a small amount, so most refugees, having lost all their property, cannot get back on their feet, let alone afford to buy a house.

Samvel Asatryan’s family has moved houses five times in the last 25 years, although now they live in the house of a relative whose family moved to Russia, so they do not pay rent. But the family of four, two of whom are children, cannot afford to buy a house.

‘The state, Georgia, makes promises, we’re waiting in line [for housing]. For years we have been waiting, and we have reached out to authorities in Tbilisi and in Gori. To the municipal government (gamgeoba) in Akhalkalaki. They say “no, wait your turn, first, we need to allocate resources to the veterans”. The programme has been running for ten years, and allocation to veterans has not finished. It was very difficult. We didn’t have anything. We arrived in the clothes we were in. We had to start from scratch. There was nothing to eat, bread was given out in rations. We survived. We were given rations, I don’t remember how many, enough for one or two loaves a month. My mother and brother live separately, my father died. My sisters are married. I would go back [to Abkhazia] with great joy, there is no better place. I went to school there, grew up there. We have a house there. We have not gone back after the war, with Georgian passports we will not be allowed to enter. Are we sorry to have come to Akhalkalaki? It’s too late for regrets’, Samvel Asatryan says.

This article is a partner post written by Kristina Marabyan. The original version first appeared on Jnews, on 26 February 2018. All place names and terminology used in this article are the words of the author alone, and may not necessarily reflect the views of OC Media’s editorial board.