Since mid-June, Georgian filmmakers and their supporters have been protesting a ‘reorganisation’ of the country’s National Film Centre by the Ministry of Culture, warning that it aims to extend full government control over the country’s cinematic output.

‘Censorship’ is the word that Gaga Chkheidze uses to describe the Ministry of Culture’s reforms at the Film Centre.

Chkheidze is the founder of the Tbilisi International Film Festival and a former board member of the Georgian Film Development Fund.

For two years from 2020, Chkheidze also acted as the director of Georgia’s National Film Centre, a standalone body under Georgia’s Ministry of Culture responsible for much of the funding and promotion of Georgia’s film industry.

But his unexpected firing in March 2022 and replacement by the deputy Minister of Culture, Kakha Sikharulidze, has become a key event in what critics consider to be a forceful takeover of the Film Centre by the ministry.

While the government maintains that Chkheidze was dismissed for financial misconduct, he and his supporters claim his firing was related to his public criticism of the ministry; a fight they have taken to court.

After the announcement of a ‘reorganisation’ of the Film Centre and a series of lay-offs in mid-2023, filmmakers and their supporters have been engaged in a campaign aimed at achieving ‘independence’ for the centre.

Protesters have spent over two months attempting to enter into dialogue with the new director and Culture Minister, but the state representatives overseeing the institution have publicly dismissed their demands.

Fearing for the future of Georgian cinema, protesters have committed to continuing and growing their protests until their demands are met.

‘Establishing control over the film centre’: a reorganisation

Over a year after Chkheidze’s dismissal, the issue was unexpectedly brought to the fore again after the Goethe Institut, a German non-profit cultural institution, awarded him the 2023 Goethe Medal.

In the announcement, the organisation stated that Chkheidze was dismissed as director after he ‘expressed criticism of Russia in the wake of Russia’s war […] on Ukraine and published a statement of solidarity with Ukraine’, attributing the decision to Georgia’s Minister of Culture.

Chkheidze similarly told OC Media that his dismissal was directly related to public statements he made after the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Two days later, the Film Centre’s Facebook page published a statement dismissing this as ‘false and hypocritical’, claiming that Chkheidze was fired on the basis of a report by the ministry’s internal audit department, which had allegedly found Chkheidze to have engaged in financial misconduct, nepotism, and ‘systematic […] violations of the Georgian legislation on purchases’. The statement also noted that financing for the Tbilisi International Film Festival was provided by the centre, which some saw as a threat to withdraw funding.

This post became the starting point for protests by members of the film industry.

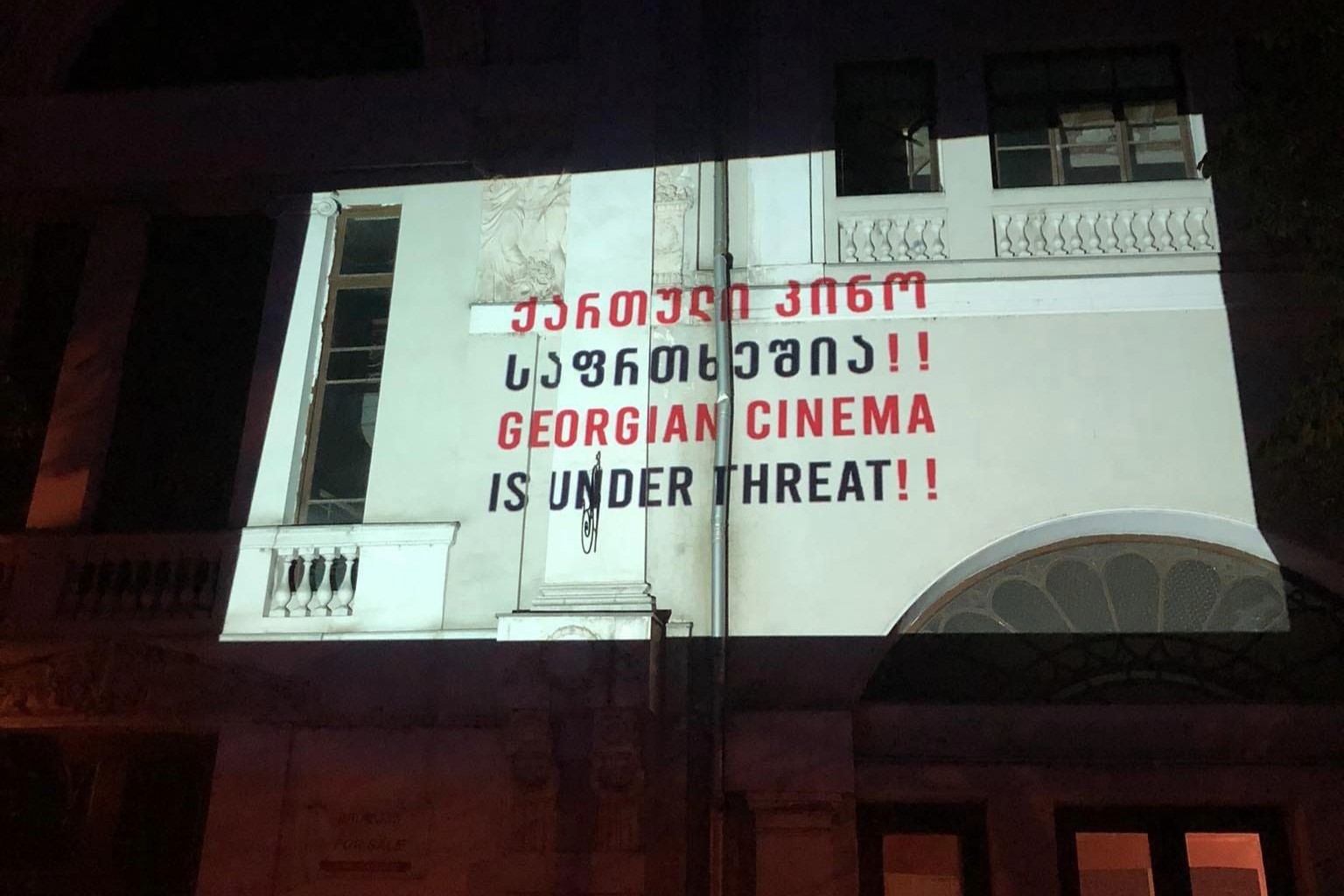

Georgian cinema is under threat / Facebook

Four employees of the Film Centre posted their objections in the days following, voicing their objection to the statement, and asserting that it had been written and published without their consent. All four were later fired.

This was followed by a joint post on the Film Centre Facebook page and website, demanding that the independence of the National Film Centre be maintained with ‘open cooperation between the representatives of the film industry and those working at the centre’, and warning of the danger of turning the cinema centre into an organisation ‘closed from the public’. Both posts were deleted the same day; protesters say by the ministry.

‘It was already obvious that interference had taken place in the activities of the Film Centre. This is not the first time, but certainly, it was the last straw, and we began to declare it loudly’, says Nino Kukhalashvili, who at that point was deputy director of the Film Centre.

‘This statement was removed from the website of the National Film Centre immediately after its publication, and the Facebook page was completely transferred to the Ministry of Culture. The Ministry of Culture occupied the film centre and abolished it’, says Chkheidze.

As filmmakers began to organise against the perceived attack, the Ministry of Culture doubled down: on 10 June, it appointed Koba Khubunaia, head of the Film Centre’s finance department, as acting director of the film centre.

Kukhalashvili says that employees were not told about Khubunaia’s appointment before it took place because the ministry had already ‘restricted access’ to legal documents and formal decisions by that time.

Khubunaia immediately announced that a month-long ‘reorganisation’ would begin on 12 June; the term ‘reorganisation’ has frequently been used by the ministry under Culture Minister Tea Tsulukiani to describe controversial mass layoffs. Those fired in previous ‘reorganisations’ at two major Georgian museums have said that people were dismissed for criticising or expressing dissatisfaction with the government.

On 11 June, Nino Kukhalashvili wrote that the process had begun at the Film Centre, and the position of deputy director had been abolished.

‘Today I received a call from the Ministry of Culture and they told me that […] I will be released from the position of deputy director from 12 July’, wrote Kukhalashvili. ‘To abolish the position of deputies, it is necessary to make a change in the regulations of the Film Centre, which of course was implemented by Tsulukiani.’

‘I have called the Film Centre a department of the Ministry of Culture for a long time, and now everything has been “put in order” legally’, wrote Kukhalashvili.

A statement signed by 502 film industry professionals, including leading cultural figures, was published on the day that the reorganisation was set to begin, accusing the Ministry of Culture of attempting to discredit the Film Centre, subjugate ‘an independent organisation’, and dictate the ‘goals and processes’ of Georgia’s film industry.

It claimed that Khubunaia had announced a ‘completely vague’ reorganisation of the organisation without any basis, and that this was an attempt to bring the Film Centre under complete political control.

The signatories made three demands: that the reorganisation be halted, that a new director be appointed through a standard competitive process, and not based on the ‘sole decision’ of the Culture Minister, and that the director be selected by a committee of representatives of the cinema sector.

While Kukhalashvili claims that the Minister of Culture promised to stop the layoffs, in the month following the announcement, the department terminated the contracts of a number of employees. According to the ‘Georgian cinema is in danger’ Facebook page, eight employees were fired, with Kukhalashvili stating that another two had chosen to leave.

At least one of the vacated posts was then given to a pro-government figure: Bacho Odisharia, a presenter on the pro-government channel, POSTV, who was given the post of deputy head of the film production department.

[Read more: Pro-government Georgian TV channel merges with anti-West group People’s Power]

While the reorganisation formally ended on 12 July, film industry professionals have continued their protests, calling for their demands to be met. They warn that the Culture Minister’s policy could irreversibly damage Georgia’s film industry, and drag it back into a Soviet-style approach, whose aim is to exert full political control over the country’s creative output.

‘Art is alive and independent’: taking action

Protests against the actions of Georgia’s Ministry of Culture, and particularly Minister of Culture Tea Tsulukiani, have been a relatively regular occurrence since her appointment in March 2021.

A series of mass firings from cultural and scientific institutions have prompted protests and lawsuits, with a number of fired employees winning their cases against the ministry.

[Read more: Georgian Culture Ministry loses wrongful dismissal lawsuits]

Apprehension regarding Tsulukiani’s intentions for Georgia’s film-makers began to grow a week after she took office, when the minister asserted that the state should finance films that ‘instil […] a love of the motherland’ in young people.

But after the events leading up to the Film Centre’s ‘reorganisation’, a protest movement launched in earnest, under the slogan ‘Georgian cinema is in danger’.

For the month of the reorganisation, protesters gathered at the office of the film centre director, reportedly daily, banging on his door to call for a meeting and that he engage with their demands.

On 29 June, protesters took their concerns to parliament. At a meeting of the Human Rights Committee, representatives of the film industry staged a protest — after the session began, they removed their jackets to reveal white t-shirts with a variety of inscriptions: no to censorship, independence to the film centre, Georgian cinema is in danger, solidarity to museums, and others. They stood silently until Mikhail Sarjveladze, the committee chair, stopped the hearing and forced them to leave the session.

Once the reorganisation officially ended on 12 July, the protests continued; around once a week, film centre employees and film industry professionals massed outside Khubunaia’s door, holding banners calling for ‘independence for the film centre’ and demanding meetings with Khubunaia and Tsulukiani. Protesters outside gave speeches and draped a banner from a nearby bridge.

Alongside these attempts to engage the ministry in dialogue, the protesters’ demands have been repeated by leading actors, musicians, filmmakers, and other figures, including the country’s president. The protest’s slogan has been displayed at theatres, before film screenings, at guerilla film projections around Tbilisi, and at film festivals in Georgia.

While diverse in their approaches, those protesting have a few core concerns regarding the encroachment of the ministry into the Film Centre.

One is the lack of experience of Khubunaia in any film-related spheres. Khubunaia remains the head of the Ministry of Culture’s economic department, and formerly worked in the prison system.

‘Over the years […] all the [centre’s] directors were film supporters, film lovers, and film professionals, they all did their best, as they imagined, and none of them came from the penitentiary system’, said director Irine Zhordania, in a report by TV Pirveli. ‘[He] will need to find out today, what is the film process, how it should be carried out correctly, and I consider such a dismissive attitude towards the entire sphere to be unacceptable’.

Speaking at a protest in June, director Nana Jorjadze was yet more blunt: ‘I have a director’s education: can I manage Georgia’s economy?’

On 21 August, after three weeks of the protests being on hiatus, filmmakers announced that they were launching an official boycott of the Film Centre, refusing to participate in its projects and competitions.

They have maintained the same demands throughout: calling for the appointment of a director through a fair process judged by film industry professionals.

‘Of course, the protest will continue, and the slogans remain unchanged. I hope the goal will be achieved because we, the protesters, are not going to stop’, Kukhalashvili says.

Snubs and inaction: Tsulukiani’s response

Protesters see the ministry’s response to their demands as dismissive at best.

On 14 July, Culture Minister Tea Tsulukiani told pro-government channel Imedi that the ministry’s decisions remained in force, and there was no possibility of a change of course.

The minister noted that the reorganisation was ‘practically completed’, and that she consequently did not understand the purpose of the protest, accusing ‘artists’ of being unaware of the ‘boring details’ of the process and consequently misunderstanding it.

The minister also suggested that meetings with film industry professionals had been taking place, with 12 or 13 individuals who had ‘presented their vision of the Film Centre’ at a previous meeting. She added that in September, this group’s viewpoints would be brought to Parliament to apply for legislative changes and ‘announce contests’.

On 22 July, Tsulukiani met with 12 film industry professionals to discuss ‘ongoing changes and reforms in the field of cinema’, budget allocation, and issues relating to the Film Centre.

However, Chkheidze claims that none of the filmmakers who participated in the protests, and who have long been demanding the opportunity to meet with Tsulukiani and Khubunaia, were present at the meeting.

‘They met with completely different people, inviting other filmmakers they considered loyal to the party’s policy. Here, there is a huge danger that the development of Georgian cinema will be subject to party dictates’, Chkheidze states.

Filmmakers who took part in the protests were also reportedly snubbed by the ministry, according to the campaign’s page. While both Tinatin Kajrishvili and Luka Beradze’s films were shown at the Karlovy Vary film festival in Czechia, a post on the Film Centre Facebook page mentioned only Kajrishvili’s film; a fact that many took to be related to Beradze’s active participation in the protests.

The Ministry of Culture did not respond to OC Media’s request for comment, first demanding ‘a signed request’, and following the submission of a signed request, ‘a signed request addressed to the ministry’.

Chkheidze suggests that turning a blind eye to issues and outlets that don’t fit the party line is characteristic of Tsulukiani’s leadership. The former head of the Film Centre says that the minister often ignores things that she ‘doesn’t like’: not attending events arranged by the Film Centre for a year, not answering official letters, and not greeting staff of the Film Centre when they met.

Journalists have similarly noted a refusal by the Culture Minister to engage with independent media outlets.

[Listen on OC Media: Podcast | Tea Tsulukiani’s chokehold on Georgian culture]

‘Despite my many attempts, from the very beginning, she built a wall between the ministry and the Film Centre and spoke to us only in the language of instructions, and she gave these instructions through her assistant, she never got in touch with us’, Chkheidze says.

Chkheidze tells OC Media that the reason for Tsulukiani’s approach is that she wants to ‘free’ Georgia’s cultural landscape from ‘disloyal and unfaithful intellectuals’.

‘This is not an attempt at reform but [an attempt to establish] something like a single line of loyalty, one might say, loyalty to one person’, says Chkheidze.

He mentions an incident in which Tsulukiani, speaking at the Senaki theatre in western Georgia, called on the audience to repeat ‘long live Bidzina Ivanishvili’, in support of the ruling party’s billionaire founder.

‘We can say that, unfortunately, Georgia’s cultural policy now follows this small phrase’, says Chkheidze.

Resilience against the odds

All of the protesting film industry figures who spoke to OC Media were determined to continue the protest, even if they were not optimistic about the results.

‘I believe and want this industry to have a great future, on behalf of the professionals who work with us today, but if the already meagre funding is not distributed fairly, political content or predetermined topics will constrain artists’, says Anna Bazhadze, a film director and current employee of the Film Centre.

She adds that Georgia has a ‘growing and modern’ film industry that needs professional employees with a good education, which she says is at odds with the government’s current policy. She notes that many filmmakers have already left Georgia to pursue their careers, and more continue to leave.

Chkheidze takes a similarly bleak view of the government’s attitude to film and culture.

‘The minister, despite the protests, did not notice anything. As if nothing is happening and these people are a minority for her who can be isolated and ignored; this is completely insulting for these people who create the future of Georgian cinema’, says Chkheidze

He believes that Tsulukiani’s policy has already affected the Film Centre and other institutions, from the firing of long-standing museum specialists after they signed a petition to ‘save’ an art museum to the recent appointment of parliamentarian Ketevan Dumbadze to the post of head of the Writers’ House.

[Read more: Ruling party member to head Georgia’s Writers’ House]

‘Today we are faced with the destruction of successful cultural institutions, incomprehensible unsubstantiated reforms, inexplicable ignorance, the closure of spaces, and the repressive politics pursued by the Ministry of Culture,’ he says.

These factors, he says, threaten to destroy Georgia’s cultural landscape.

Some have suggested that cultural institutions may join forces to collectively face down the ministry’s advances, with Luka Beradze, a filmmaker and member of the protests, telling OC Media that there had been discussion between members of the filmmakers’ protest movement and those associated with the Writer’s House.

But in the meantime, the filmmakers continue their fight.

In the letter announcing their boycott of the ‘kidnapped’ Film Centre, the almost 300 signatories assert their refusal to ‘become a participant in the process leading to the destruction of modern Georgian cinema, culture, and science’.

‘Only in the conditions of a democratically elected leader will the Film Centre be able to ensure freedom of speech, expression, and creativity for Georgian filmmakers’, the text asserts.

Kukhalashvili says that while the ministry wants only films ‘they need and fully control’ to be produced, they can expect to be met with resistance.

How this fight ends remains to be seen. But it is clear that Georgia’s artists are determined to fight to hold on to their independence, and to defend a position repeated in chants, on posters, and in public declarations: that art is ‘alive, independent, and political’.