In Photos | 365 days of consecutive protest in Georgia

It has been a year since Georgian Dream announced its EU u-turn, prompting mass protests — OC Media has captured it all.

Georgia is no stranger to protests. This year, however, was different, with thousands of Georgians continuing to protest on a daily basis to support their country’s EU aspirations and against the Georgian Dream’s government’s anti-Western policies.

The protests also took place off the heels of the disputed October 2024 elections, which handed Georgian Dream another term in power.

Though protesters gathered on Rustaveli Avenue throughout the year, the size of these demonstrations has shrunk over time. Their future as yet remains uncertain.

On the one-year anniversary of the protests, OC Media looked back at all the major events that have taken place.

November 2024

The daily anti-government protests began when Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced the ruling Georgian Dream party’s decision to halt the country’s EU-integration process. Thousands came to Tbilisi’s central Rustaveli Avenue to protest the decision. In response, riot police began dispersing the crowd using water cannons, tear gas, and pepper spray. This was the start of around two weeks of clashes between riot police and protesters, who in turn used fireworks as a means of resistance.

From the earliest days of the protest, police began arresting people using excessive force. Initially, when media tried to film the brutal arrests, police interfered with journalists and photographers by damaging or seizing their phones and other equipment.

During the first few days, dozens of journalists were attacked and injured. Some of them received life threatening injuries, including Guram Rogava, who was attacked by police during a live broadcast. He spent months in rehabilitation before he could go back to work.

December 2024

The mass arrests of protesters continued in December, with over 450 detained in just the first two weeks of protests. According to local civil society organisations and the Public Defender’s Office, the vast majority of detainees experienced violence at the hands of the police.

Protesters started to adapt to the dispersals by equipping themselves with protective gear. They also figured out how to disable tear gas canisters fired by the police.

As protesters’ methods changed, so did that of the riot police, who would deploy massive amounts of tear gas to create a noxious fog on the street before unexpectedly arresting people indiscriminately.

During one such attempt, a police officer tried to arrest OC Media’s reporter and co-founder Mariam Nikuradze. After learning she was a member of the press, police pushed her up against a wall and destroyed her second camera — the first had been destroyed during the initial days of dispersals.

The government also increased the administrative fine for blocking the road from ₾500 ($180) to ₾5,000 ($1,800), turning it into a heavy financial burden for protesters.

Eventually, in mid-December, Tbilisi City Hall began decorating Rustaveli Avenue with Christmas decorations and set up a Christmas tree in front of the parliament building. Despite police presence, and repeated removals, people began decorating the tree with protest banners and photos of tortured protesters on a daily basis.

City Hall has also failed to conduct the traditional lighting of the tree due to the ongoing protests. Eventually, it was lit without fanfare.

January 2025

Protesters rang in the New Year on Rustaveli Avenue by organising a big feast table outside the parliament.

When the riot police dispersals died out after Georgian Dream banned fireworks, facemasks, lasers, and other protest items, protests turned more peaceful. Different groups of people began organising thematic marches from various corners of the city, which continued in January as well.

On 12 January, a dinner was organised for judges at a restaurant in Tbilisi, which took place against the backdrop of protests against the biased justice system. Demonstrators notably confronted judges outside the restaurant, throwing eggs at them.

One of the judges tried to get to his car and failed; he then tried to get onto a bus, the driver of which failed to open the door for him in time. At that point, someone threw an egg at his head.

On 12 January, the founder of local independent media outlets Batumelebi and Netgazeti, Mzia Amaghlobeli, was detained in Batumi. Protests to support her were organised both there and in Tbilisi.

In a separate initiative, a group of protesters launched smaller marches in urban areas of Tbilisi. In an act of disobedience, some of them wore facemasks, which led to several arrests.

Protesters also attempted to enact a general strike. It lasted three hours, with participants from all across the country and various sectors.

Separately, in support of the criminally charged actor Andro Chichinadze, theatre actors moved their protest to the streets, with one theatre taking a play to different regions of Georgia to raise awareness about the situation in the country.

Against the backdrop of the ongoing protests, the Council of the EU decided to suspend the visa-free regime for diplomatic passports issued in Georgia.

A few days later, the Georgian Government announced they were freezing their participation in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), after the body voted to accept the Georgian delegation’s credentials on the condition new parliamentary elections be announced.

February 2025

On 2 February, protesters attempted to block one of Tbilisi’s main exits, something that Georgian Dream made a criminal offence.

Heavy police presence ensured people could not block the exit — however, such presence instead itself made it impossible for cars to move freely. Several people were arrested that day, including opposition leaders.

A few days later, Georgian Dream established its commission to punish the former ruling United National Movement (UNM) party, a commission whose mandate gradually expanded to cover effectively all opposition parties. Throughout 2024, Georgian Dream had repeatedly vowed to punish the UNM, notably accusing the party of provoking and starting the August 2008 War.

As tensions continued to rise, more marches were organised with the demand of snap elections.

March 2025

Along with the traditional gathering at Rustaveli Avenue, a group of protesters had been marching daily from the Georgian Public Broadcaster to the main protest site in front of parliament — the march was to demand fair coverage of ongoing events in the country and to protest the broadcaster’s editorial policy and their firing of employees on political grounds.

The marches saw protesters with drums and megaphones making noise along the route. At the end, they would read out the names of imprisoned protesters outside parliament.

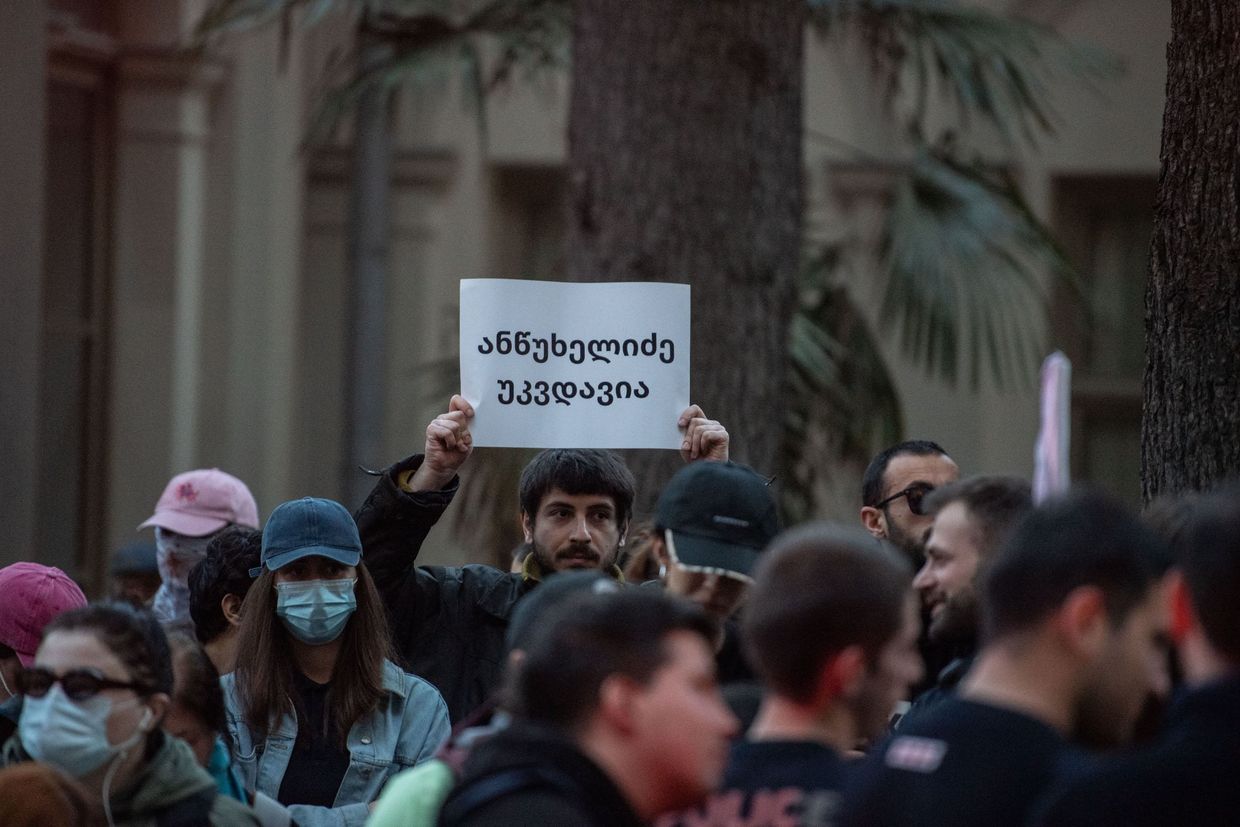

People also began protesting the work of the anti-opposition parliamentary committee established in February. One strand of this related to Georgia’s national hero, Giorgi Antsukhelidze, who was tortured and killed during the August 2008 War. During a committee hearing, MP Tea Tsulukiani claimed that ‘Antsukhelidze was sacrificed for somebody’s ambitions’, alluding to former President Mikheil Saakashvili.

On the government side, in their first parliamentary hearings, Georgian Dream approved a series of amendments and legislation, including what the party claimed was a Georgian translation of the US Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) meant to replace the controversial foreign agent law.

Separate amendments to the broadcasting law prohibited broadcasters from receiving direct or indirect funding — including money or other material benefits of property value — from ‘a foreign power’.

The laws were unanimously passed by the ruling party in the absence of opposition in parliament

April 2025

During commemorations to mark the 36th anniversary of the brutal crackdown by Soviet troops on pro-independence demonstrators in Tbilisi on 9 April 1989, protesters gathered and stayed overnight on Rustaveli Avenue. The aim was to pay tribute to the victims and to confront the government officials who would come the next day.

In turn, Georgian Dream leaders used the anniversary to attack domestic and foreign critics, drawing parallels between today’s anti-government demonstrators and the Soviet troops. The ruling party officials also notably avoided mentioning Russia in their commemorative statements.

Throughout the year, Tbilisi City Hall’s Animal Monitoring Agency removed the protest dogs, several of whom were never seen again.

In mid-April, the government cracked down on civil society by restricting foreign grants for civil society and media organisations. The parliament also adopted a law limiting donations to political parties.

As with previous holidays, protesters also marked Easter together, gathering outside Kashveti Cathedral on Rustaveli Avenue with candles and saying prayers together.

Towards the end of the month, police raided the homes of protest fund organisers in an attempt to further pressure demonstrators, many of whom by this point were facing large fines for road-blocking — OC Media’s Nikuradze had accumulated fines worth over $7,000, despite being clearly labeled as press.

After the introduction of these fines, people began to get creative on how to avoid being recognised by AI face recognition cameras.

May 2025

On Labour Day — after visiting protesters in the mining city of Chiatura, where a separate protest has also been going for months — some protesters marked the day by expressing solidarity with the Chiatura protest.

Despite the chilly winter days and rainy spring, the protest never stopped — sometimes there would be less people, but they would still block the road.

Beginning in April and continuing in the following months, larger marches were organised in different parts of Tbilisi with protesters carrying large Georgian and EU flags, as well as photos of imprisoned protesters.

After marching, people would go into the metro and continue their protest there before eventually going back to the parliament — ‘home’, as many protesters now call the place.

People also marked Europe Day on 9 May by marching to Tbilisi’s Europe square with Georgian and EU flags.

Later that month, alongside government-organised events, pro-European activists held marches to commemorate Georgia’s Independence Day on 26 May. A rally also took place outside parliament that evening, where Georgia’s fifth president Salome Zourabichvili and Lithuanian MEP Rasa Juknevičienė made speeches.

Towards the end of the month, police began detaining opposition leaders after they failed to attend the Georgian Dream parliamentary commission to investigate the opposition.

June 2025

In the beginning of summer, mothers of imprisoned protesters started going into different districts of Tbilisi — as well as other cities, villages, and towns all over Georgia — to meet with people face to face, explain how democracy was declining in the country, and distribute newspapers containing letters from both prisoners and their family members.

As restrictions continued, protesters kept coming up with new forms of resistance.

In June, a small group of protesters began using zebra crossings to express their dissent and to spread their messages to drivers. On one occasion, a car ran into protesters, injuring some of them. Protester Mariam Mekantsishvili had her rib broken as result of the incident.

On the 200th day of protest, demonstrators burnt the Russian flag outside the parliament building. To protect their identities, and make a statement, the protesters wore Guy Fawkes’ masks, as popularised in the film V For Vendetta. They also chanted ‘revolution, while spraypainting the same word around the parliament building.

Mid-way through the month, Georgian Dream initiated a new bill to severely restrict media coverage of court trials. At the same time, the ruling party proposed doubling the salaries of judges.

July 2025

In July, the body of Vano Nadiradze, a Georgian fighter in Ukraine, was returned to Georgia. Unlike in other cases, Nadiradze’s body was not met with the traditional military guard, leaving protesters to organise a welcome for him. Many went to his funeral in Kashveti Cathedral.

A new tradition began in the summer of family members and friends marking the birthdays of imprisoned protesters outside their prisons.

After being imprisoned, orphaned protester Archil Museliantsi, who found an adoptive mother in Tsaro Oshakmashvili — another demonstrator who met him during the ongoing protests — began studying for the national exams in prison. With the help of Tsaro, he managed to pass the national exams in July. Tsaro went to each of his exams to support him.

As the summer continued, some days were calm, without any major events, though the protests kept going.

In July, families, including IDPs and socially vulnerable households, were evicted in Tbilisi’s Samgori District. The authorities stated that the occupants were living there illegally and that the buildings were unsafe for habitation. To support them, protesters visited the district. Police arrested 17 people as a result.

In the hot summer days, protesters began bringing water guns to cool off and have some fun with their children on Rustaveli Avenue.

August 2025

In August, many sentences were announced for detained protesters. Journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli was among them — she was sentenced to two years in prison. The mothers of other detained or imprisoned protesters travelled to Batumi to support her during her final court hearings.

Among these trials, there was an unexpected turn in three cases of imprisoned protesters charged with the possession of drugs. Facing eight to 20 years in prison, all three were cleared of charges.

As Georgian Dream adopted repressive legislation to suppress local independent media, 22 media outlets decided to unite and crowdfund for their survival, as well as to show solidarity and increase awareness about the dire situation in terms of freedom of speech and expression. The campaign was named ‘The lights must stay on’.

September 2025

More sentences came for dozens of protesters in September.

As the local elections neared, Georgian Dream’s mayoral candidate Kakha Kaladze opened his election headquarters on Melikishvili Avenue. The headquarters became a hotspot for clashes between protesters and Georgian Dream supporters.

Georgian Dream supporters attacked protesters, injuring some of them. They also attacked media workers. While an investigation was formally launched, no one was ever punished.

One demonstrator, Megi Diasamidze, left a protest message on an election poster. She was arrested on criminal charges the next day. While she was granted bail, she still faces up to five years in prison.

In solidarity with Diasamidze, the leader of the opposition Droa party, Elene Khoshtaria, also wrote a note on Kaladze’s election banner — she was arrested on the same charges shortly afterwards. She refused to pay the bail and remains in prison to this day.

In mid-September, Georgian courts began jailing protest participants after repeated offences for ‘blocking roads’, in particular, for not paying the associated fines.

October 2025

In early October, women organised a march in solidarity with the imprisoned protesters.

The most pressing event this month, however, was the 4 October local elections.

The ruling Georgian Dream party won a landslide in the local elections, a vote that was boycotted by the largest opposition groups.

In parallel with the election, thousands took the streets.

In a failed attempt to storm the presidential residence, people once again clashed with the riot police on Orbeliani Square.

Following the elections, 64 people were arrested on criminal charges.

In October, new, even stricter regulations came into force in an attempt to stop protesters from blocking the road. In particular, this offence became punishable by up to 15 days of administrative detention and up to one year in prison in case of repeated offence.

Despite the new regulations, dozens of people kept blocking Rustaveli Avenue. Up to 150 people have served administrative detentions for offences like blocking the road, wearing a face-mask, disobeying police, or insulting police since the regulations came to force, including Zurab Menteashvili. He became the first person to face criminal charges for blocking the road — he now faces up to one year in jail and is being held in pre-trial detention.

For several weeks, protesters ignored the new repressive laws, and kept blocking Rustaveli Avenue. Ioseb Kheoshvili, a protester with a disability, was among them, even after being detained. Due to his disability status, he was not given time in prison, but fined ₾5,000 ($1,800) three times.

In October, an investigation was launched against two-time former Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili for corruption. He made his first appearance in court on 24 October, where he agreed to cooperate with investigators. He faces up to 12 years in prison.

On 26 October, protesters marked the one year anniversary of Georgia’s controversial parliamentary elections.

In October, Nino Datashvili, a protester who was arrested for ‘attacking a court bailiff’ in Tbilisi City Court, and who is facing four to seven years in jail, was released on bail after her health severely deteriorated.

November 2025

In early November, Georgian authorities brought new charges against almost all major opposition leaders, including attempting to carry out a coup, sabotage, unlawful coordination with foreign countries, and more. Those charged face up to 15 years in prison if convicted.

Despite the new restrictive laws, as people kept blocking Rustaveli, hundreds of police officers were mobilised to physically restrict protesters from blocking the road as the one-year anniversary of the protests neared.

In response, people began organising marches on the smaller streets surrounding parliament.

Eventually, police started to restrict even these marches, including by blocking protesters from the pavement, which is not yet prohibited by law.

Dozens were detained during these marches on charges of resisting or insulting police — in most cases, however, police failed to prove the charges in court. Despite this, the courts have consistently sentenced those detained to fines or administrative detention.

In recent days, anyone who held a megaphone to lead a march would get arrested.

On 25 November, protesters brought handcuffs to link themselves together in an effort to avoid being arrested.

Despite the waning numbers of protesters on Georgia’s streets, hundreds, if not thousands, continue to attend protests on a daily basis.

How long this will last is yet unclear. What is clear, however, is Georgian Dream’s rapid descent into authoritarianism.